Octostruma

| Octostruma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Octostruma iheringi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Octostruma Forel, 1912 |

| Type species | |

| Rhopalothrix simoni (junior synonym of Octostruma iheringi) | |

| Diversity | |

| 35 species (Species Checklist, Species by Country) | |

The ant genus Octostruma is restricted to the Neotropics. These ants inhabit the leaf litter and soil in forests.

Identification

Octostruma belong to the tribe Basicerotini. This tribe is taxonomically problematic as there is no single accepted classification of its species into genera. Baroni Urbani and de Andrade (2007) synonymized the tribe Basicerotini with the Dacetini and proposed that all basicerotine genera be placed in the genus Basiceros. Longino (2013) revised Octostruma, recognizing 34 species, and stated the genus is "a heterogeneous assemblage, held together solely by the 8-segmented antenna."

| See images of species within this genus |

Keys to Species in this Genus

Distribution

Distribution and Richness based on AntMaps

Species by Region

Number of species within biogeographic regions, along with the total number of species for each region.

| Afrotropical Region | Australasian Region | Indo-Australian Region | Malagasy Region | Nearctic Region | Neotropical Region | Oriental Region | Palaearctic Region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Species | 2841 | 1736 | 3045 | 932 | 835 | 4379 | 1741 | 2862 |

Biology

Longino (2013) - Brown and Kempf (1960) summarized the biology of basicerotines as follows: The basicerotines all come from tropical or subtropical areas, and predominantly from mesic habitats, particularly rain forest, where they live primarily in the upper layers of the soil and in the soil cover, including large and small pieces of rotten wood. They are fairly common in soil cover berlesates. Nests have been found in snail shells, and in the peaty masses gathered about epiphytic ferns above the ground level. So far as is known, colonies are small, consisting of one or more dealate—or rarely ergatoid—females, and a few workers. Judging from the structure of the workers and females, one would suppose that they were predaceous on small arthropods...

Besides this summary, the behavior of three basicerotine species has been studied. Wilson (1956) observed a small captive colony of Eurhopalothrix biroi, a New Guinea species. Workers moved slowly and captured a variety of small, soft-bodied prey, including spiders, symphylans, entomobryid Collembola, campodeids, and hemipteran nymphs. Wilson and Brown (1984) observed a captive colony of Eurhopalothrix heliscata, a species from Singapore. The colony contained over 400 workers, multiple alate and dealate queens, several adult males, and brood. Foraging workers acted "rather like miniature ferrets," readily wedging themselves into small crevices. They foraged solitarily, attacking a variety of prey but mostly termites. They used their sharply-toothed mandibles to abruptly snap onto appendages of prey, maintaining purchase and slowly reaching around with the gaster to sting the prey. The strongly sclerotized labrum was also employed to press against the clamped appendage. The behavioral repertoire was limited. There did not appear to be trophallaxis, as workers and larvae fed directly from prey in the brood chambers. Nor did there appear to be any form of alarm communication. While there was generally an increase in the number of foragers when clusters of prey were presented, there was no evidence of any pheromone-based recruitment. Workers were non-aggressive and responded to disturbance by tucking the appendages and becoming immobile, often for minutes at a time. Wilson and Hölldobler (1986) studied captive colonies of Basiceros manni from Costa Rica and observed behavior not substantially different from E. heliscata. Foraging workers of many basicerotines are often encrusted with a firmly bonded layer of soil, which is thought to function as camouflage, enhancing crypsis (Hölldobler & Wilson, 1986).

Knowledge of the basic natural history of these ants has hardly progressed since the observations of Wilson, Brown, and Hölldobler. More specimens are now available for examination due to quantitative litter sampling, enhancing knowledge of basicerotine diversity and distribution, but discovering nests remains exceedingly difficult. Quantitative samples of 1 m2 litter plots reveals that small basicerotines can be very frequent, occurring in over 50% of samples in some cases, but never in large numbers. Individual samples usually contain fewer than ten workers, and workers are often accompanied by dealate queens. These results suggest that colonies, at least among New World species, are usually small, with tens of workers.

Life History Traits

- Mean colony size: "A few workers" (Greer et al., 2021)

- Compound colony type: not parasitic (Greer et al., 2021)

- Nest site: hypogaeic (Greer et al., 2021)

- Diet class: predator (Greer et al., 2021)

- Foraging stratum: subterranean/leaf litter (Greer et al., 2021)

Castes

Less than half of the species of Octostruma have their queens described. Ergatoid queens are known from Octostruma rugifera and other species. Males are known from collections for some species but none have been described. The mating biology of these ants and how common ergatoid queens are across the genus and within colonies is not known.

Morphology

Worker Morphology

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

• Antennal segment count: 8 • Antennal club: 2 • Palp formula: 1,2 • Total dental count: 6-12 • Spur formula: 0, 0 • Eyes: 2-10 ommatidia • Pronotal Spines: absent • Mesonotal Spines: absent • Propodeal Spines: dentiform • Petiolar Spines: absent • Caste: none or weak • Sting: present • Metaplural Gland: present • Cocoon: absent

Male Morphology

Explore: Show all Male Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Male Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

• Antennal segment count 13 • Antennal club 0 • Palp formula 1,2 • Total dental count 1-2 • Spur formula 0, 0

Phylogeny

| Myrmicinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See Phylogeny of Myrmicinae for details.

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- OCTOSTRUMA [Myrmicinae: Basicerotini]

- Octostruma Forel, 1912e: 196 [as subgenus of Rhopalothrix]. Type-species: Rhopalothrix simoni (junior synonym of Rhopalothrix iheringi), by subsequent designation of Wheeler, W.M. 1913a: 82.

- Octostruma raised to genus: Brown, 1948e: 102.

- Octostruma junior synonym of Basiceros: Baroni Urbani & De Andrade, 2007: 88.

Taxonomic Notes

All taxa of genera Eurhopalothrix, Octostruma, Protalaridris, Rhopalothrix and Talaridris were combined in Basiceros, sensu Baroni Urbani & De Andrade, 2007: 90-93. Synonymy of all basicerotine genera under Basiceros, by Baroni Urbani & De Andrade, 2007: 88, is incorrect procedure as Rhopalothrix has priority. Basicerotine genus-rank taxonomy documented in Bolton, 2003: 183-185, is retained.

Longino (2013) provided the following regarding key characters for the genus:

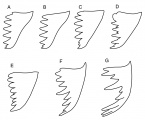

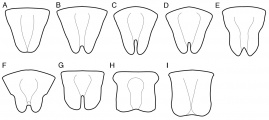

Octostruma workers vary greatly in the shape of the labrum and in mandibular dentition. Unfortunately, these two characters are rarely visible on point-mounted museum specimens, which typically have the mandibles closed. Identification is much easier if the mandibles are spread prior to examination. When examining specimens in fluid or preparing fluid-stored specimens for dry-mounting, an insect pin can be driven between the mandibles from the ventral side, wedging one of the mandibles open. A single open mandible is often sufficient to see the dentition and the labrum shape.

The labrum always has a raised transverse rim on the dorsum, immediately anterior to the articulation with the head capsule. The lateral margins are thickened and form two "arms", joined by thinner cuticle medially, which variously project forward or converge to form the shape of the anterior margin. The anterior margins of Octostruma labra bear a fringe of translucent setae that are best seen in fluid. These setae are soft, relatively thick, and often capitate. They look more like the translucent papillae of a marine organism than the typical sclerotized setae of insects, and their function is unknown.

The mandible is a complex three-dimensional structure that is triangular in cross section, with three faces: dorsal, ventral, and interior. The dorsal face is usually in the same plane as the clypeus, and there is a prominent basal ridge that abuts the clypeus when the mandible is closed. The dorsal face rounds into the ventral face which is flat to shallowly concave. The ventral face meets the interior face at a sharp, well-demarcated angle. The interior face is moderately to strongly concave. The masticatory margin, with serial teeth, is at the juncture of the interior and dorsal faces. The dorsal face is usually roughened, while the ventral and interior faces are smooth and shining. The teeth of the masticatory margin are prominent. A convention used in this paper is to number the teeth from the base, such that tooth one is adjacent to the basal rim. In some species the basal rim of the dorsal face is offset from the first tooth, forming a small denticle that is a continuation of the basal rim. Some species have denticles between the major teeth, and these are not numbered. Each of the main teeth typically has an appressed seta that extends from the base of the tooth to or near the apex, on the dorsal surface. There is often a thin layer of clay-like material adhering to the mandibular teeth, and the appressed tooth setae may play a role in soil adherence ("holding setae" of Hölldobler and Wilson, 1986).

- Longino (2013). Click on any image to see a larger version of the drawings.

Mandibles of Octostruma workers. Drawings are not to scale. A. O. triangulabrum, O. wheeleri, O. triquetrilabrum. B. O. cyrtinotum, O. gymnosoma, O. montanis, O. planities, O. schusteri. C. O. iheringi. D. O. balzanicomplex: O. amrishi, O. balzani, O. batesi, O. betschi, O. gymnogon, O. lutzi, O. megabalzani, O. stenognatha, O. trithrix. E. O. excertirugis, O. obtusidens. F. O. rugiferoides. G. O. ascrobis, O. convallis.

Labra of Octostruma workers. Drawings are not to scale. A. O. leptoceps, O. triquetrilabrum, O. triangulabrum, O. wheeleri. B. O. gymnosoma, O. schusteri. C. O. cyrtinotum, O. montanis, O. planities. D. O. iheringi. E. O. balzanicomplex: O. amrishi, O. balzani, O. batesi, O. betschi, O. gymnogon, O. lutzi, O. megabalzani, O. stenognatha, O. trithrix. F. O. excertirugis, O. obtusidens. G. O. rugiferoides. H. O. ascrobis, O. convallis. I. O. pexidorsum.

Full face view of Octostruma species, showing outline of headcapsule and disposition of spatulate setae. Depictions of seta number and location are species averages and individuals may vary. A. O. trithrix, O. lutzi (part). B. O. balzani, O. lutzi (part), O. megabalzani. C. O. amrishi. D. O. gymnogon. E. O. iheringi. F. O. obtusidens. G. O. excertirugis. H. O. leptoceps. I. O. wheeleri. J. O. triangulabrum. K. O. triquetrilabrum. L. O. cyrtinotum. M. O. gymnosoma. N. O. schusteri. O. O. planities. P. O. montanis. Note the enlarged seta pits on O. iheringi, O. cyrtinotum, and O. montanis. Drawings are not to same scale.

The setae on the dorsal surfaces of the body fall into two discrete categories: (1) abundant, short, appressed-to-curved setae; and (2) sparse, long, erect setae that are clavate, spatulate, or in the form of brushes. Hölldobler and Wilson (1986) referred to these as "holding" and "brush" setae, respectively, associating them with putative soil-binding and camouflage functions. The holding setae were hypothesized to enhance adherence of a soil layer, while brush setae functioned to gather the soil particles that the holding setae would anchor. Among the Central American Octostruma, some species certainly seem to support this hypothesis. The face is nearly always covered with a thin, cement-like soil layer that covers the underlying cuticle. The holding setae are embedded in the soil layer, while the brush setae project above. However, many species rarely have a soil layer, yet they still have the erect brush setae and, albeit sparsely, the underlying holding setae. Thus, I refer to these as the clavate or spatulate setae and ground pilosity, respectively.

The erect spatulate setae are variously disposed on the face, dorsal mesosoma, and gaster. They are easily seen and usually there is no other erect pilosity. The number and location of the setae are highly constrained on the face and mesosoma, with species varying in the presence or absence of setae at a number of "landmark" positions. Highly similar species, especially in the O. balzani complex, may differ in the presence or absence of a single seta. However, identification is often bedeviled by both variation (missing or additional setae) and by setae lost due to wear.

Queens are only slightly larger than workers. The meso- and metasoma are enlarged relative to workers, but mean HW varies from 1–1.2 times mean HW of the corresponding workers. Intercaste workers are common. They are larger than typical workers, may have a more convex mesosoma, and often have additional erect setae on the face and mesosomal dorsum.

References

- Baroni Urbani, C.; De Andrade, M. L. 1994. First description of fossil Dacetini ants with a critical analysis of the current classification of the tribe (Amber Collection Stuttgart: Hymenoptera, Formicidae. VI: Dacetini). Stuttg. Beitr. Naturkd. Ser. B (Geol. Paläontol.) 198: 1-65 (page 31, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Dacetini)

- Bolton, B. 1994. Identification guide to the ant genera of the world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 222 pp. (page 105, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Basicerotini)

- Bolton, B. 1998a. Monophyly of the dacetonine tribe-group and its component tribes (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. Entomol. Ser. 67: 65-78 (page 67, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Basicerotini)

- Bolton, B. 2003. Synopsis and Classification of Formicidae. Mem. Am. Entomol. Inst. 71: 370pp (page 184, Octostruma as genus)

- Boudinot, B.E. 2019. Hormigas de Colombia. Cap. 15. Clave para las subfamilias y generos basada en machos. Pp. 487-499 in: Fernández, F., Guerrero, R.J., Delsinne, T. (eds.) 2019d. Hormigas de Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1198 pp.

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1948e. A preliminary generic revision of the higher Dacetini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 74: 101-129 (page 102, Octostruma as genus, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Dacetini)

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1949h. Revision of the ant tribe Dacetini: IV. Some genera properly excluded from the Dacetini, with the establishment of the Basicerotini new tribe. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 75: 83-96 (page 92, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Basicerotini; Octostruma as genus)

- Brown, W. L., Jr.; Kempf, W. W. 1960. A world revision of the ant tribe Basicerotini. Stud. Entomol. (n.s.) 3: 161-250 (page 181, Octostruma as genus)

- Cantone S. 2018. Winged Ants, The queen. Dichotomous key to genera of winged female ants in the World. The Wings of Ants: morphological and systematic relationships (self-published).

- Donisthorpe, H. 1943g. A list of the type-species of the genera and subgenera of the Formicidae. [part]. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 11(10): 617-688 (page 676, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Dacetini)

- Emery, C. 1924f [1922]. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Myrmicinae. [concl.]. Genera Insectorum 174C: 207-397 (page 328, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Dacetini; Octostruma as subgenus of Rhopalothrix)

- Fernandez, F., Guerrero, R.J., Sánchez-Restrepo, A.F. 2021. Sistemática y diversidad de las hormigas neotropicales. Revista Colombiana de Entomología 47, 1–20 (doi:10.25100/socolen.v47i1.11082).

- Forel, A. 1912f. Formicides néotropiques. Part II. 3me sous-famille Myrmicinae Lep. (Attini, Dacetii, Cryptocerini). Mém. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 19: 179-209 (page 196, Octostruma as subgenus of Rhopalothrix)

- Forel, A. 1917. Cadre synoptique actuel de la faune universelle des fourmis. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 51: 229-253 (page 246, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Dacetini; Octostruma as subgenus of Rhopalothrix)

- Hanisch, P.E., Sosa-Calvo, J., Schultz, T.R. 2022. The last piece of the puzzle? Phylogenetic position and natural history of the monotypic fungus-farming ant genus Paramycetophylax (Formicidae: Attini). Insect Systematics and Diversity 6 (1): 11:1-17 (doi:10.1093/isd/ixab029).

- Longino, J. T. 2013. A revision of the ant genus Octostruma Forel, 1912 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Zootaxa 3699:1-61. [2013-08-09]

- Wheeler, W. M. 1913a. Corrections and additions to "List of type species of the genera and subgenera of Formicidae". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 23: 77-83 (page 82, Type-species: Rhopalothrix simoni (junior synonym of Octostruma iheringi), by subsequent designation)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1922i. Ants of the American Museum Congo expedition. A contribution to the myrmecology of Africa. VII. Keys to the genera and subgenera of ants. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 45: 631-710 (page 667, Octostruma in Myrmicinae, Dacetini; Octostruma as subgenus of Rhopalothrix)

- Wilson, E.O. & Brown, W.L. Jr. 1984. Behavior of the cryptobiotic predaceous ant Eurhopalothrix heliscata, n. sp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Basicerotini). Insectes Sociaux. 31*Wilson, E.O. 1956. Feeding behavior in the ant Rhopalothrix biroi Szabó. Psyche (Cambridge), 63:21–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/1956/23572

- 408–428.