Formica polyctena

| Formica polyctena | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Formicini |

| Genus: | Formica |

| Species: | F. polyctena |

| Binomial name | |

| Formica polyctena Foerster, 1850 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

A wood ant, which is one of a number of Palearctic Formica species that build complexes of large mound nests, have large numbers of workers and collect honeydew.

| At a Glance | • Polygynous • Supercolonies • Temporary parasite • Diploid male |

Photo Gallery

Identification

Erect hairs on head and mesosoma very sparse and short or absent, except on posterior margins of mesopleura. Gula hairs, if present, are restricted to one or two very weak hairs. Microsculpture is usually slightly coarser than in Formica rufa but punctures and micropunctures are widely spaced as in that species. Length: 4.0-8.5 mm (Collingwood 1979).

Keys including this Species

- Key to Palaearctic Formica rufa group species

- Key to Palaearctic species in the Formica rufa group

- Key to Formica species of the subgenus Formica of Greece

Distribution

Spain to Siberia, Italian Alps to latitude 60º in Sweden (Collingwood 1979).

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 68.969° to 41.614444°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Oriental Region: India.

Palaearctic Region: Albania, Andorra, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany (type locality), Greece, Hungary, Iberian Peninsula, Italy, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

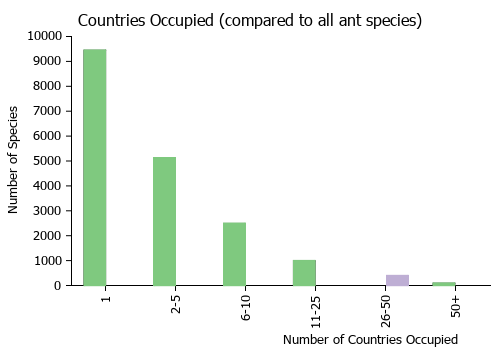

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Habitat

Borowiec and Salata (2022) - Occurs mainly in deciduous and fir forests, less frequently in coniferous forests. Nests are large, especially in fir forests nests of vegetable mounds can be up to 2 m in height. In deciduous forests nests are smaller. In open warm places nests are flat with rudimentary layer of plant material or only with crater of mineralic soil material in which the plant material is restricted to a rudimentary central disc.

Biology

Collingwood (1979) - This is accepted as a good species by most European authors, eg. Betrem (1960), Dlussky (1967), Kutter (1977). Some samples of Formica rufa tend to approach the hairless condition of F. polyctena however, making certain determination sometimes difficult. Elton (priv. communication) found that F. polyctena in its most typical form readily accepted fertile queens and pupae from other distant nests of the same species but were always antagonistic to and rejected such from both polygonous and monogynous colonies of F. rufa. This is usually found in a group of nests and always has many queens, sometimes up to 1,000 or more.

This is a relatively well studied species and one that had long confounded myrmecologists in regards to its specific taxonomic identity. Collingwood's statements above are indicative of these problems. What follows is a more recent summary that provides insight into our latest understanding of this ant. This is taken from Seifert et al (2011). The details for the cited works are given in the original publication.

The wood ant species Formica polyctena and Formica rufa are important elements of temperate forest ecosystems of the West Palaearctic. They are considered to give protection against a number of pest insects in natural and secondary, managed forests (reviewed by Otto 1967) and are a symbol and main target of nature conservation in many countries of Europe. Yarrow (1955) and Betrem (1960) considered F. polyctena and F. rufa as clearly different species and this view had been generally adopted for 35 years. The situation changed when Seifert (1991) published a comprehensive study on external morphology and biological parameters of 430 nests collected in different regions of Central, East and North Europe. In addition to the typical F. polyctena and F. rufa, he found a third entity which was intermediate in each investigated phenotypic or biological character: body size, eight size-corrected pilosity characters, monogyny frequency, size of nest populations, diameter of nest mounds and infestation rate with epizootic fungi. He concluded that the third entity was a fertile hybrid between F. polyctena and F. rufa.

Foraging/Diet

Formica polyctena collect large quantities of honeydew.

Novgorodova (2015b) investigated ant-aphid interactions of a dozen honeydew collecting ant species in Western Siberia pine and aspen-birch-pine forests (54°7´N, 83°06´E, 200 m, Novosibirsk) and mixed-grass-cereal steppes with aspen-birch groves (53°44´N, 78°02´E, 110 m, near Karasuk) in the Novosibirsk Region and coniferous forests in the northeastern Altai (north end of Lake Teletskoe, 51°48´N, 87°17´E, 434 m). All of the ants studied had workers that showed high fidelity to attending particular aphid colonies, i.e, individual ants tend to return to the same location, and group of aphids, every time they leave the nest. F. polyctena's honeydew collecting activities were highly coordinated during the summer months when the aphids and ants were most active. Individual foragers specialized on specific tasks and could be classified as shepherds (collect honeydew), guards (protect aphids from competitors), scouts (search for new aphid colonies) and transporters (transport honeydew to the nest). Individuals performed the same type of work day after day, with groups of the same workers, thereby forming teams. In cooler months when aphids were still active foragers were less specialized: some ants were "on duty" (constantly present in a particular aphid colony, collecting honeydew and /or protecting aphids from various competitors) and others that showed no specialization. F. polyctena tended: Symydobius oblongus (Heyden), Chaitophorus populeti (Panzer), Aphis jacobaeae Schrank and A. grossulariae Kaltenbach.

Nesting Habits

Formica polyctena often forms huge supercolonies with several hundred nests. Nests can be vary large, particularly in coniferous forests.

Rybnikova and Kuznetsov (2015) studied nest complexes of wood ants in the Darwin Nature Reserve (Rybinsk Reservoir basin, Vologda and Yaroslavl Provinces, Russia). Their work assessed, in part, how wild boars and seasonal flooding may influence the survival and viability of wood ant colonies.

A complex of raised and transitional sphagnum bogs is developed in the central part of the peninsula. The better drained areas near the shores are occupied by a strip of upland forests from 1 to 5 km wide, mostly represented by green moss, tall moss, and complex pine forests blending into sphagnum pine forests closer to the bogs. Small patches of lichen pine forests are present in the raised areas. The biotic complex of the reserve is affected by the water level fluctuations in the reservoir, due to which its vast shallow peripheral areas are annually flooded and exposed. However, the water level not only changes seasonally within one year but also varies from year to year, so that high-water and low-water years occur. The destruction of mature ant nests by boars leads to complete elimination of many colonies and stimulates fragmentation of the surviving colonies in spring. The results of exogenous fragmentation of the damaged nests include a decrease in the number of large nests, loss of their growth potentials, depopulation, and degradation. Regular and largescale destruction of ant nests by boars leads to rapid degradation and dying off of whole nest complexes (Dyachenko, 1999; Efremov, 2013).

Observations of the ants have been carried out since 1997. The parameters recorded were the number of inhabited nests in the complexes (n), the basal diameter of the nest dome (d), and the diameter of the nest mound (D).

The Eastern complex (Formica polyctena) is located in a maturing green moss pine forest with admixture of spruce and birch in the first layer, the second layer of spruce, and undergrowth of rowan and juniper. In 2001–2004, the complex comprised 30 nests with the mean basal diameter of 130 ± 38 cm and the mean dome height of 45 ± 16 cm. In 2005, the number of nests started to decline, and only 15 nests remained by 2010. The mean dome base diameter decreased nearly twofold, to 70 ± 31 cm, but the dome height was only insignificantly reduced, to 30 ± 16 cm.

The Southern complex (Formica polyctena) is located in a maturing green moss pine forest. In 1997 the complex included 11 inhabited nests, and in 2004, of 14 nests. The largest nest was fragmented after being destroyed by a wild boar in the winter of 1995, and in 1997 it consisted of three domes on a common mound. It also gave rise to several secondary nests which were built inside an area fenced off with mesh. These nests were never destroyed by boars; they are still quite viable and have distinctly conical domes. The size of the three fenced-off nests practically did not change since 1997. The mean basal diameter (d) of all the nests of the complex only slightly changed since the end of the 1990s: it was 150 ± 40 cm (n = 14) in 1998 and 135 ± 50 cm (n = 8) in 2010. At the same time, the dome height (h) decreased almost twofold, from 85 ± 28 cm (n = 14) in 1998 to 45 ± 40 cm (n = 8) in 2010, due to annual destruction of most nests by wild boars.

Silon Island is a tall ridge of glacial origin. The ant communities of the island were studied in the late 1990s (Rybnikova and Kuznetsov, 1998). The greatest part of the island is occupied by a lichen pine forest which provides little food for red wood ants; therefore, foraging mostly takes place in the riparian zone.

The complex of Silon Island—South. A small complex of F. polyctena exists under the above conditions in the southern part of the island. In 1997, the complex included 18 inhabited nests, which were large, conical, and connected with distinct trails. Some of them reached 70 cm in height (h) and 150–200 cm in dome diameter (d). All the nests were positioned along the shore. The foraging trails extended into the temporary inundation zone, where at a low water level the abundant periaquatic vegetation supported numerous aphid colonies. Since 2003 until now, the water level in the reservoir has remained high, and periaquatic vegetation has been reduced to a narrow stripe of sedges where ants cannot forage. As a result, only three nests have remained there by 2010, all of them being annually destroyed by bears and, less frequently, by boars. The complex is now declining due to a profound reduction of the trophic resources and repeated nest destruction.

Nest Splitting

Mabelis (1979a) - 1. In the red wood ant, nest splitting is accompanied by the formation of one or more daughter nests. During this process, which can last a week, a month or even longer, transport of workers, queens and brood from the mother to the daughter nest occurs and often in the opposite direction as well. 2. Transpor t of congeners can occur throughout the season in which the red wood ant is active. 3. Transport between a mother nest and a daughter nest can be the result of: a. a difference in the accessibility of the main source of food, b. an attack by the population of a neighbouring nest and/or c. a change in the condition of the nest itself. The predominant direction in which transport occurs can be interred from the environmental conditions of the nests. 4. For removals, transport occurs in only one direction. Some of the ants transported during a removal were observed to return to the nest from which they had been taken. This prolonged the removal. 5. The number of transporters increased during the removal process. This increase is shown to be ascribable to a considerable extent to the transmission of information; in other words, other ants in the nest are in some way stimulated by the transporters to start to participate in the transport.

Behavior

Holecová et al. (2016) found Formica polyctena to exhibit higher foraging activity between mid-November and mid-March in Slovakia.

Regional Notes

Borowiec and Salata (2022), for Greece - The only known locality of this species is from an area with deciduous forest. Workers and gyne were collected at an altitude of 974 m.

Wood Ant Wars

Mabelis (1979b) - In a dune area near The Hague (The Netherlands) nest populations of Formica polyctena are common. The number of nests was counted over a period of five years. The number of the inhabited nests remained almost constant in this period (ca. 23 nests per 4 ha.). Nest populations of Formica polyctena give rise to new nests by means of nest splitting. In the study area 17 viable daughter nests were established in a period of five years.

This means that nest populations merged and/or died off. Ten mergers were observed in this period (all of them between mother and daughter nests), and seven populations died off. Since there was a surplus of suitable nest sites, the question was raised as to whether the disappearance of populations could be due to intra- specific competition for food or even to intraspecific aggression. To find out whether, and if so how, aggression is related to the food requirements of a population, the aggressive behaviour as well as the food supply of nest populations were investigated.

In the spring, after hibernation, increasing numbers of wood ant workers swarm out from the nest into the surrounding area. Many of them move in the direction of the most important food sources of the preceding year: trees and bushes with many aphids. The observations indicated that the workers can remember throughout the winter period the direction in which major food sources were located in the preceding year. Some of the workers travel farther from the nest, especially on warm days; and consequently the frequency of meetings between workers from neighbouring nests increases. Since new nests usually arise by splitting off from existing nests, neighbouring nests are generally of the same origin. Meetings between their workers can result in voluntary transport or in an aggressive encounter. The longer two nests are isolated from each other, the more the number of transported ants declines and the number of victims increases as the result of meetings. An increasing difference in odour between the populations may be responsible for this pattern. Experiments have shown that, when given a different diet, isolated populations of the same origin behaved more aggressively toward each other the longer the separation had lasted.

Locally, the number of fighting ants can increase rapidly due to storage and transfer of information about the battle: ants can remember the location of the battlefield for a long time, and they can attract the attention of other workers by means of scent substances and conspicuous behaviour. As a result, a war can develop to a point at which thousands of ants are involved.

The casualties (thousands per day) are dragged to the warring nests. A few days later (marked) casualties were found on the dumping ground, i.e. a place situated a few metres from the nest to which remnants of prey and dead ants are brought from the nest. The ant bodies brought from the nest to the dumping ground were found to be about half as heavy as those brought from the battlefield to the nest. The findings showed that the workers in the nest are responsible for the loss in bodyweight; in other words, casualties are consumed in the nest by the workers. The majority of the former are aliens; these function as prey. It is assumed that ants seeking for prey are more easily recruited for a war than aphid milkers, because predators have a weaker route- and task-fidelity than do aphid milkers and are also more aggressive.

Almost all wars break out in early spring, especially on warm days. At night, the number of ants on a war track drops sharply, in contrast to the number on tracks leading to aphid trees, which remains nearly constant. This means that most of the workers involved in a battle during the day stay in the nest during the night. They leave the nest early in the morning and go straight to the battlefield of the preceding day, thus contributing to the heavy traffic observed during a short period in the morning.

Early in a war there is a strong positive correlation between the temperature and the number of casualties. This is explained by the fact that when temper- ature rises, the number of foragers increases as well as their aggressiveness. However, at a certain moment in the spring the effect of temperature on the number of casualties disappears. After that, the daily number of casualties declines and the war comes to an end. At the last, the density of foragers on the now peaceful battlefield becomes so low that we can speak of a "no-man's-land" between the foraging areas of populations.

As a result, the frequency of meetings between workers from neighbouring nests is low at such times, i.e. during the summer. Meetings which do occur lead less often to casualties, because the readiness of workers to attack congeners in the border area between nests is lower than it was early in the spring, and under these con- ditions there is a greater chance of reaching home safely by resorting to fleeing or appeasement behaviour. Nevertheless, ants from different nests are still hostile to each other: when they were lured to the same place (by means of prey items) war- fare revived. However, when this occurs, there are fewer casualties and the duration of the battle is shorter than in the beginning of the year. During the spring and summer each nest has its own territory, i.e. an area around the nest where intruders belonging to neighbouring nests are attacked (Figs. 5 and 6, see back fold).

One of the functions of intraspecific aggression may be defence and enlargement of the territory, to secure as large a food supply as possible for the nest population. Changes in territory size occur mainly during wartime in the spring. Large populations have the advantage here over small ones, because the more workers a population sends into battle, the more bodies the nest will acquire and the greater the chance of enlarging its territory. As a result, large populations generally possess larger territories than small populations do. In autumn, the number of ants in some parts of the border area increases again, but the neighbours are no longer hostile toward each other and the foraging areas of their nests show an overlap. Thus, intraspecific aggression is strongest in the spring, at the start of the reproduction period, when the protein requirement of the nest is high and the prey density in the field is low. The hypo- thesis is put forward that wars occur in periods when the prey requirement is higher than the supply. Experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis was provided by experiments performed in the laboratory: populations given a prey-poor diet became more aggressive after a few weeks than did sister populations which received a prey- rich diet.

Because war casualties are consumed for the benefit of the queens and the growing larvae, the main function of warfare may be the reduction of the risk that maturing larvae will receive too little protein-rich food at times when there is a low prey density. The casualties in a war are workers belonging to the oldest generation. The toll taken by war thus concerns individuals which will die soon anyway, and whose task (i.e.predation) cannot be fulfilled maximally because of lack of prey. Every population sacrifices, as it were, a proportion of its workers in times of food scarcity for the sake of the food supply for the first stages of the new generation, which will finally mature in a time when food is abundant in the field.

There are striking similarities between the behaviour of workers with respect to prey and foreign congeners:

a. descriptively, predatory and aggressive behaviour are similar;

b. for a worker, a prey and a non-nestmate have qualitatively the same value as external stimulus; and

c. the motivations for these two kinds of behaviour cannot be distinguished from each other.

There seem to be no essential differences between predatory and aggressive behaviour. Experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis was obtained by offering prey items to warrior ants. Where a large number of prey items were set out among battling ants on a battlefield, the number of war casualties temporarily decreased, and where prey items were set out on the track to the battlefield at night, the daily resumption of a war could be delayed; the warriors reacted immediately to the prey, which they dragged to the nest. It is therefore concluded that warfare in the red wood ant can be considered a form of mutual predation.

Worker Rescue

Milar et al. (2017) found in an experimental test, simulating being threatened with entrapment in sand (as might happen if falling in an ant lion pit or if subjected to a collapse of a ground nest), that this species did exhibit rescue behaviour. This was in agreement with their hypothesis that species that could face entrapment situations would show such a response. Formica polyctena occur in forest situations. While they have not evolved with ant lion predation they do face possible dangers from being stuck in clay, organic debris or plant secretions. Milar et al. suggested this species had developed a general rescue cue and response that applied even when threatened with an ant lion, which was a novel threat.

This species is known to suffer from labial gland disease, a condition caused by an unknown agent (Elton, 1989; Elton, 1991).

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a temporary parasite for the ant Formica (Serviformica) species (a host) (de la Mora et al., 2021; Ruano et al., 2018; Seifert, 2018).

- This species is a host for the ant Formica sanguinea (a dulotic parasite) (Seifert, 2018; de la Mora et al., 2021).

- This species is a host for the ant Formica truncorum (a temporary parasite) (de la Mora et al., 2021; Seifert, 2018) (single observation).

- This species is a xenobiont for the ant Formicoxenus nitidulus (a xenobiont) (Holldobler & Wilson 1990; Busch 2001; Martin et al. 2007).

- This species is a host for the beetle Monotoma angusticollis (Coleopotera: Monotomidae) (a myrmecophile) in Europe (Wagner et al., 2020).

- This species is a host for the nematode Oscheius dolichura (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (multiple encounter modes; indirect transmission; transmission outside nest).

Hemiptera

This species is associated with the aphids Aphis brohmeri, Aphis craccivora, Aphis evonymi, Aphis fabae, Aphis jacobaeae, Aphis pomi, Aphis subnitidae, Callipterinella tuberculata, Chaitophorus albitorosus, Chaitophorus albus, Chaitophorus populeti, Chaitophorus populialbae, Chaitophorus salicti, Cinara boerneri, Cinara laricis, Cinara piceae, Cinara pinea, Cinara pini, Glyphina betulae, Macrosiphoniella pulvera, Rhopalosiphum padi, Schizaphis gramina, Schizaphis pyri and Symydobius oblongus (Saddiqui et al., 2019 and included references).

Trematoda

- This species is a host for the trematode Dicrocoelium dendriticum (a parasite) in Denmark (Botnevik et al., 2016; de Bekker et al., 2018).

Fungi

- This taxon is a host for the fungi Aegeritella superficialis (Pascovici, 1983; Espadaler & Santamaria, 2012), Ophiocordyceps myrmecophila (Shrestha et al., 2017), Pandora myrmecophaga (Boer, 2008; Csata et al., 2013) and Pandora formicae (Małagocka et al., 2017).

- This species is a host for the fungus Pandora myrmecophaga (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

Zingg et al. (2018) found that F. polyctena were negatively correlated with the abundance of ticks in a field study conducted in the forests of the Jura Mountains, northwestern Switzerland. They examined the abundance of nymph and adult ticks in paired sites with and without F. polycenta. They found: the presence of red wood ants was negatively associated with the number of questing Ixodes ticks. Ant nest volume was the most important ant related variable and had a strong negative effect on tick abundance. The mechanisms that drive the negative relationship between wood ants and ticks remain unknown.Possible mechanisms include the repellent effect of ant formic acid, and the predatory behavior of the wood ants.

The records of this species being enslaved by Formica aserva noted by Ruano et al. (2019) are in error as this species is outside the geographic distribution of F. aserva (Palearctic host, Nearctic parasite) (de la Mora et al., 2021).

Transplanting Colonies

Nielson et al (2018) showed how colonies of this species could be usefully moved into cultivated areas in Denmark to help control pest species.

Flight Period

| X | X | X | |||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Life History Traits

- Queen number: polygynous (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

- Queen type: winged (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992) (queen-right worker reproduction)

- Colony type: supercolony

- Mean colony size: 450,000 (Rosengren, 1971; Kruk-de-Bruin et al., 1977; Horstmann, 1982; Beckers et al., 1989)

- Nest site: thatch mound

- Foraging behaviour: trunk trail (Rosengren, 1971; Kruk-de-Bruin et al., 1977; Horstmann, 1982; Beckers et al., 1989)

Castes

Worker

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0173642. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0173866. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Diploid males are known to occur in this species (found in 6.9% of 72 examined nests) (Pamilo et al., 1994; Cournault & Aron, 2009).

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- major. Formica major Nylander, 1849: 29 (w.) FINLAND. Junior synonym of rufa: Emery & Forel, 1879: 450. Revived from synonymy: Betrem, 1926: 213. Senior synonym of piniphila: Betrem, 1953: 325. Junior synonym of rufa: Yarrow, 1955a: 3; Betrem, 1960b: 76; Kutter, 1977c: 273; of polyctena: Radchenko, 2007: 37 (major is best regarded as a nomen oblitum, therefore polyctena takes priority).

- polyctena. Formica polyctena Foerster, 1850a: 15 (w.q.m.) GERMANY. Junior synonym of rufa: Nylander, 1856b: 60; Emery & Forel, 1879: 450; Dalla Torre, 1893: 208; Yarrow, 1955a: 3. Subspecies of rufa: Forel, 1915d: 58; Emery, 1925b: 253; Stitz, 1939: 339; Boven, 1947: 189. Status as species: Bondroit, 1917a: 174; Müller, 1923: 144; Betrem, 1926: 212; Betrem, 1960b: 64; Dlussky, 1967a: 93; Dlussky & Pisarski, 1971: 187; Kutter, 1977c: 272; Collingwood, 1979: 144. Senior synonym of minor: Betrem, 1960b: 64; Dlussky, 1967a: 93; of nuda: Dlussky, 1967a: 93; Dlussky & Pisarski, 1971: 187; of major: Radchenko, 2007: 37 (major is best regarded as a nomen oblitum, therefore polyctena takes priority). See also: Mabelis, 1979: 451; Gösswald, 1989: 18; Atanassov & Dlussky, 1992: 279; Czechowski & Douwes, 1996: 125.

- nuda. Formica (Formica) rufa var. nuda Karavaiev, 1930b: 148 (w.) SWEDEN. [Unresolved junior primary homonym of nuda Ruzsky, above.] Junior synonym of rufa: Karavaiev, 1936: 240; Yarrow, 1955a: 4; of polyctena: Dlussky, 1967a: 93; Dlussky & Pisarski, 1971: 187.

- minor. Formica minor Gösswald, 1951: 436 (w.q.) GERMANY. [First available use of Formica rufa subsp. pratensis var. minor Gösswald, 1941: 78; unavailable name.] Junior synonym of polyctena: Betrem, 1960b: 64; Dlussky, 1967a: 93.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Borowiec and Salata (2022) - Very large, HL: 1.780-2.160 (mean 1.928); HW: 1.508-1.920 (mean 1.660); SL: 1.508-1.820 (mean 1.646); EL: 0.479-0.571 (mean 0.512); ML: 2.36-2.83; MW: 1.14-1.37. Color. Head bicolours, clypeus, genae, sides behind eyes and ventral side yellowish red to red, rest of surface brown to black, sometimes clypeus in the middle with obscure spot or dark pattern of head limited only to occipital part of head, yellowish red of anterior part of head gradually turn into the dark posterior part of head without sharp border between pale and dark parts; mesosoma uniformly yellowish red to red, often pro- and anterior part of mesonotum at top with dark brown to black spot with relatively sharp borders but yellow or reddish always predominate, petiolar scale usually yellowish red to red, occasionally upper margin slightly obscure, gaster brown to black with transparent white posterior margin of tergites, anterior slope of first tergite often with yellowish red to pale brown spot, antennal scapi from uniformly reddish to completely brown, funicle from yellowish brown to dark brown, legs in pale forms with reddish coxa and trochanters, reddish brown femora and tibiae and reddish tarsi, in dark forms completely brown with slightly paler brown tarsi. Head. Broad, 1.1-1.2 times longer than wide, in front of eyes softly converging anterad, behind eyes softly rounded, occipital margin straight to slightly concave. Clypeus without or with obtuse median keel, on the whole surface distinctly microsculptured, often partly longitudinally striate, slightly trapezoidal, its anterior margin convex, sides convergent posterad, posterior margin truncate, whole clypeal surface with very short and sparse appressed pubescence, anterior margin with a row of 14-16 moderately long to long setae, the longest in the middle with length 0.114, rest of clypeal surface without or with a row of 4 long setae close to anterior margin and 2-6 short erected setae in the middle and close to base of clypeus. Head distinctly microreticulate, appears indistinctly dull and opaque, with very short and very sparse appressed pubescence not covering head surface, usually lacking erected setae, occasionally with single seta in ocellar area and 1-2 short setae in occipital corners, ventral side of head without, erected setae. Scape short, 0.9-1.0 times as long as width of head, thin, distinctly reaching beyond the occipital margin, distinctly, regularly widened from base to apex, its surface microreticulate, with short and dense appressed pubescence, erected setae absent. Funicular segments elongate, thin, first segment 1.6 times as long as second segment, the second segment 1.6-1.7 times as long as wide, distinctly shorter than third segment, the rest of funicular segments clearly longer than broad. Eyes big, elongate oval, approximately 0.26 length of head. Mesosoma. Elongate in dorsal view distinctly constricted in the middle, 2.0-2.3 times as long as wide, dorsally and laterally distinctly microreticulated, surface indistinctly dull and opaque. In lateral view promesonotum convex, mesonotal groove deep, propodeum strongly, obtusely convex. Whole mesosomal surface covered with long and sparse appressed pubescence not covering the mesosomal surface, usually on dorsum lacking erected setae, occasionally each segment wit 1-5 very short standing setae, the longest with length 0.048. Waist and gaster. Petiolar scale broad, moderately thick in lateral view, apex truncate usually with very shallow median emargination, margins without or with 2-4 short, erected setae. Tergites 1-2 and often also tergite 3 lacking row of apical setae, surface of tergites numerous short to moderately long erected setae. Legs. Ventral surface of both fore femora usually with 2-5 short erected setae, of mid femora without setae.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- n = 26, 2n = 52 (Finland; Switzerland) (Hauschteck-Jungen & Jungen, 1976; Rosengren et al., 1980).

References

- Alexandrovna, K.A. 2020. Red wood ants (Formica s. str.) as a method of biological protection in phytocenoses of the Mordovia Republic. In: Vavilov Readings - 2020: a collection of articles of the International Scientific and Practical Conference dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the law of homological series and the 133rd anniversary of the birth of Academician NI Vavilov, November 24-25, 2020.

- Antonov, I.A., Bukin, Yu.S. 2016. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the ant genus Formica L. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Palearctic region. Russian Journal of Genetics 52(8), 810–820 (doi:10.1134/s1022795416080020).

- Atanassov, N.; Dlussky, G. M. 1992. Fauna of Bulgaria. Hymenoptera, Formicidae. Fauna Bûlg. 22: 1-310 (page 279, see also)

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Beckers R., Goss, S., Deneubourg, J.L., Pasteels, J.M. 1989. Colony size, communication and ant foraging Strategy. Psyche 96: 239-256 (doi:10.1155/1989/94279).

- Beresford, J. 2021. The role of hybrids in the process of speciation; a study of naturally occurring Formica wood ant hybrids. Academic Dissertation, University of Helsinki.

- Berkelhamer, R.C. 1980. Reproductive strategies in ants: A comparison of single-queened versus multiple-queened species in the subfamily Dolichoderinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Berton, F., Lenoir, A., Newbahari, E., Barreau, S. 1991. Ontogeny of queen attraction to workers in the ant Cataglyphis cursor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux 38: 293-305.

- Betrem, J. G. 1926. De mierenfauna van Meijendel. Levende Nat. 31: 211-220 (page 212, Status as species)

- Betrem, J. G. 1960b. Ueber die Systematik der Formica rufa-gruppe. Tijdschr. Entomol. 103: 51-81 (page 64, Status as species, Senior synonym of minor)

- Boer, P. 2008. Observations of summit disease in Formica rufa Linnaeus, 1761 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 11. 63-66.

- Bondroit, J. 1917a. Notes sur quelques Formicidae de France (Hym.). Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 1917: 174-177 (page 174, Status as species)

- Borowiec, L. 2014. Catalogue of ants of Europe, the Mediterranean Basin and adjacent regions (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Genus (Wroclaw) 25(1-2): 1-340.

- Borowiec, L., Salata, S. 2022. A monographic review of ants of Greece (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Vol. 1. Introduction and review of all subfamilies except the subfamily Myrmicinae. Part 1: text. Natural History Monographs of the Upper Silesian Museum 1: 1-297.

- Borowiec, M.L., Cover, S.P., Rabeling, C. 2021. The evolution of social parasitism in Formica ants revealed by a global phylogeny. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2026029118 (doi:10.1073/pnas.2026029118).

- Botnevik, C.F., Malagocka, J., Jensen, A.B., Fredensborg, B.L. 2016. Relative effects of temperature, light, and humidity on clinging behavior of metacercariae-infected ants. Journal of Parasitology 102, 495–500 (doi:10.1645/16-53).

- Boulay, R., Quagebeur, M., Godzinska, E.J., Lenoir, A. 1999. Social isolation in ants: Evidence of its impact on survivorship and behavior in Camponotus fellah (Hymenoptera, Formicidae).

- Boven, J. K. A. van. 1947b. Liste de détermination des principales espèces de fourmis belges (Hymenoptera Formicidae). Bull. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 83: 163-190 (page 189, Variety/subspecies of rufa)

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Chen, Y., Zhou, S. 2017. Phylogenetic relationships based on DNA barcoding among 16 species of the ant genus Formica (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from China. Journal of Insect Science 17(6): 117; 1–7 (doi:10.1093/jisesa/iex092).

- Collingwood, C. A. 1979. The Formicidae (Hymenoptera) of Fennoscandia and Denmark. Fauna Entomol. Scand. 8: 1-174 (page 144, Status as species)

- Cournault, L., Aron, S. 2009. Diploid males, diploid sperm production, and triploid females in the ant Tapinoma erraticum. Naturwissenschaften 96: 1393–1400 (doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0590-1).

- Csata, E., Czekes, Z., Eros, K., Nemet, E., Hughes, M., Csosz, S., Marko, B. 2013. Comprehensive survey of Romanian myrmecoparasitic fungi: new species, biology and distribution. North-western Journal of Zoology 9: 23-29.

- Csősz, S., Báthori, F., Gallé, L., Lőrinczi, G., Maák, I., Tartally, A., Kovács, É., Somogyi, A.Á., Markó, B. 2021. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Hungary: Survey of ant species with an annotated synonymic inventory. Insects 16;12(1):78 (doi:10.3390/insects12010078).

- Csosz, S., Marko, B., Galle, L. 2011. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Hungary: an updated checklist. North-Western Journal of Zoology 7: 55-62.

- Czechowski, W., Marko, B., Radchenko, A., Slipinski, P. 2013. Long-term partitioning of space between two territorial species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and their effect on subordinate species. European Journal of Entomology 110(2): 327–337.

- Czechowski, W., Radchenko, A. 2006. Formica lusatica SEIFERT, 1997 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), an ant species new to Finland, with notes on its biology and the description of males. Myrmecologische Nachrichten 8: 257-262.

- Czechowski, W., Radchenko, A., Czechowska, W. 2002. The ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Poland. MIZ PAS Warsaw.

- Czechowski, W., Rutkowski, T., Stephen, W., Vepsäläinen, K. 2016. Living beyond the limits of survival: wood ants trapped in a gigantic pitfall. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 51, 227–239 (doi:10.3897/jhr.51.9096).

- Czechowski, W.; Douwes, P. 1996. Morphometric characteristics of Formica polyctena Foerst. and Formica rufa L. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the Gorce Mts; interspecific and intraspecific variations. Ann. Zool. (Warsaw) 46: 125-141 (page 125, see also)

- Dalla Torre, K. W. von. 1893. Catalogus Hymenopterorum hucusque descriptorum systematicus et synonymicus. Vol. 7. Formicidae (Heterogyna). Leipzig: W. Engelmann, 289 pp. (page 208, Junior synonym of rufa)

- de Bekker, C., Will, I., Das, B., Adams, R.M.M. 2018. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and their parasites: effects of parasitic manipulations and host responses on ant behavioral ecology. Myrmecological News 28: 1-24 (doi:10.25849/myrmecol.news_028:001).

- de la Mora, A., Sankovitz, M., Purcell, J. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies. Myrmecological News 30: 53-71 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:053).

- Dekoninck, W., Ignace, D., Vankerkhoven, F., Wegnez, P. 2012. Verspreidingsatlas van de mieren van België. Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 148: 95-186.

- Dekoninck, W., Maebe, K., Breyne, P., Hendrickx, F. 2014. Polygyny and strong genetic structuring within an isolated population of the wood ant Formica rufa. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 41, 95–111 (doi:10.3897/jhr.41.8191).

- D'Ettorre, P., Heinze, J. 2001. Sociobiology of slave-making ants. Acta ethologica 3, 67–82 (doi:10.1007/s102110100038).

- Dlussky, G. M. 1967a. Ants of the genus Formica (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, g. Formica). Moskva: Nauka Publishing House, 236 pp. (page 93, Status as species, Senior synonym of minor, Senior synonym of nuda)

- Dlussky, G. M.; Pisarski, B. 1971. Rewizja polskich gatunków mrówek (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) z rodzaju Formica L. Fragmenta Faunistica 16: 145-224 (page 187, Status as species, Senior synonym of nuda)

- Dolezal, A.G. 2010. Caste determination in arthropods, In Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, edited by Michael D. Breed and Janice Moore, Academic Press, Oxford, pages 247-253.

- Dolezal, A.G. 2019. Caste determination in arthropods. In: Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, 2nd edition, Volume 4: 691–698 (doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20815-7).

- Elton, E.T.G. 1989. On transmission of the labial gland disease in Formica rufa and Formica polyctena (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen: Series C: Biological and Medical Sciences 92: 415-459.

- Elton, E.T.G. 1991. Labial gland disease in the genus Formica (Formicidae, Hymenoptera). Insectes Sociaux 38, 91-93 (doi:10.1007/BF01242717).

- Emery, C. 1925d. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Formicinae. Genera Insectorum 183: 1-302 (page 253, Variety/subspecies of rufa)

- Emery, C.; Forel, A. 1879. Catalogue des Formicides d'Europe. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 5: 441-481 (page 450, Junior synonym of rufa)

- Espadaler, X., Santamaria, S. 2012. Ecto- and Endoparasitic Fungi on Ants from the Holarctic Region. Psyche Article ID 168478, 10 pages (doi:10.1155/2012/168478).

- Fedoseeva, E.B., Grevtsova, N.A. 2020. Flight muscles degeneration, oogenesis and fat body in Lasius niger and Formica rufa queens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Russian Entomological Journal 29, 410–420 (doi:10.15298/rusentj.29.4.08).

- Foerster, A. 1850a. Hymenopterologische Studien. 1. Formicariae. Aachen: Ernst Ter Meer, 74 pp. (page 15, worker, queen, male described)

- Forel, A. 1915d. Fauna insectorum helvetiae. Hymenoptera. Formicidae. Die Ameisen der Schweiz. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 12(B Beilage: 1-77 (page 58, Variety/subspecies of rufa)

- Fournier, D., de Biseau, J.-C., De Laet, S., Lenoir, A., Passera, L., Aron, S. 2016. Social structure and genetic distance mediate nestmate recognition and aggressiveness in the facultative polygynous ant Pheidole pallidula. PLOS ONE 11, e0156440. (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156440).

- Frizzi, F., Masoni, A., Migliorini, M., Fanciulli, P.P., Cianferoni, F., Balzani, P., Giannotti, S., Davini, G., Frasconi Wendt, C., Santini, G. 2020. A comparative study of the fauna associated with nest mounds of native and introduced populations of the red wood ant Formica paralugubris. European Journal of Soil Biology 101, 103241. (doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2020.103241).

- Glaser, F. 2016. Artenspektrum, Habitatbindung und naturschutzfachliche Bedeutung von Ameisen (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) am Stutzberg (Vorarlberg, Österreich). inatura – Forschung 34: 26 S.

- Goropashnaya, A.V., Fedorov, V.B., Seifert, B., Pamilo, P. 2012. Phylogenetic relationships of Palaearctic Formica species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) based on mitochondrial Cytochrome b sequences. PLoS ONE 7, e41697 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041697).

- Goropashnaya, Anna V.; Fedorov, Vadim B.; Pamilo, Pekka 2004. Recent speciation in the Formica rufa group ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): inference from mitochondrial DNA phylogeny. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32(1): 198-206 (mtDNA sequence data)

- Gösswald, K. 1989. Die Waldameise. Band 1. Biologische Grundlagen, Ökologie und Verhalten. Wiesbaden: AULA-Verlag, xi + 660 pp. (page 18, see also)

- Haelewaters, D., Boer, P., Noordijk, J. 2015. Studies of Laboulbeniales (Fungi, Ascomycota) on Myrmica ants: Rickia wasmanniii in the Netherlands. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 44, 39–47 (doi:10.3897/jhr.44.4951).

- Helantera, H., Sundstrom, L. 2007. Worker reproduction in Formica ants. The American Naturalist 170: E15-E25.

- Holecová, M., Klesniaková, M., Hollá, K. & Šestaková, A. (2016). Winter activity of ants in scots pine canopies in Borska Nizina lowland (SW Slovakia). Folia faunistica Slovaca, 21: 239–243.

- Johnson, C.A. 2000. Mechanisms of dependent colony founding in the slave-making ant, Polyergus breviceps Emery (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ph.D. thesis, City University of New York.

- Juhász, O., Bátori, Z., Trigos-Peral, G., Lőrinczi, G., Módra, G., Bóni, I., Kiss, P., Aguilon, D., Tenyér, A., Maák, I. 2020. Large- and Small-Scale Environmental Factors Drive Distributions of Ant Mound Size Across a Latitudinal Gradient. Insects 11, 350 (doi:10.3390/INSECTS11060350).

- Juhász, O., Fürjes-Mikó, Á., Tenyér, A., Somogyi, A.Á., Aguilon, D.J., Kiss, P.J., Bátori, Z., Maák, I. 2020. Consequences of climate change-induced habitat conversions on Red Wood Ants in a central European mountain: A case study. Animals 10, 1677 (doi:10.3390/ani10091677).

- Kutter, H. 1977c. Hymenoptera, Formicidae. Insecta Helv. Fauna 6: 1-298 (page 272, Status as species)

- Laciny, A. 2021. Among the shapeshifters: parasite-induced morphologies in ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) and their relevance within the EcoEvoDevo framework. EvoDevo 12, 2 (doi:10.1186/s13227-021-00173-2).

- Maák, I., Tóth, E., Lenda, M., Lőrinczi, G., Kiss, A., Juhász, O., Czechowski, W., Torma, A. 2020. Behaviours indicating cannibalistic necrophagy in ants are modulated by the perception of pathogen infection level. Scientific Reports 10, 17906 (doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74870-8).

- Mabelis, A. 1984a. Aggression in wood ants (Formica polyctena Foerst., Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Aggressive Behavior. 10:47-53.

- Mabelis, A. A. 1979b. Wood ant wars. The relationship between aggression and predation in the red wood ant (Formica polyctena Foerst.). Netherlands Journal of Zoology 29: 451-620.

- Mabelis, A. A. 1979a. Nest splitting by the red wood ant (Formica polyctena Foerster). Netherlands Journal of Zoology. 29:109-125.

- Mabelis, A. A. 1984b. Interference between wood ants and other ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Netherlands Journal of Zoology. 34:1-20.

- Mabelis, A. A. 2003. Do Formica species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) have a different attack mode? Annales Zoologici. 53(4):667-668.

- Mabelis, A. A. 2007. Do ants need protecting? Entomologische Berichten (Amsterdam). 67(4):145-149.

- Mabelis, A. A. and J. Korczyńska. 2016. Long-term impact of agriculture on the survival of wood ants of the Formica rufa group (Formicidae). Journal of Insect Conservation. 20(4):621-628. doi:10.1007/s10841-016-9893-7

- Malagocka, J., Eilenberg, J., Jensen, A.B. 2019. Social immunity behaviour among ants infected by specialist and generalist fungi. Current Opinion in Insect Science 33, 99–104 (doi:10.1016/j.cois.2019.05.001).

- Małagocka, J., Grell, M.N., Lange, L., Eilenberg, J., Jensen, A.B. 2015. Transcriptome of an entomophthoralean fungus (Pandora formicae) shows molecular machinery adjusted for successful host exploitation and transmission. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 128, 47–56 (doi:10.1016/j.jip.2015.05.001).

- Małagocka, J., Jensen, A.B., Eilenberg, J. 2017. Pandora formicae, a specialist ant pathogenic fungus: New insights into biology and taxonomy. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 143, 108–114 (doi:10.1016/j.jip.2016.12.007).

- Meurville, M.-P., LeBoeuf, A.C. 2021. Trophallaxis: the functions and evolution of social fluid exchange in ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 31: 1-30 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:001).

- Miler, K., B. E. Yahya, and M. Czarnoleski. 2017. Pro-social behaviour of ants depends on their ecological niche-Rescue actions in species from tropical and temperate regions. Behavioural Processes. 144:1-4. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.08.010

- Miler, K., Turza, F. 2021. “O Sister, Where Art Thou?”—A review on rescue of imperiled individuals in ants. Biology 10, 1079 (doi:10.3390/biology10111079).

- Müller, G. 1923b. Le formiche della Venezia Guilia e della Dalmazia. Boll. Soc. Adriat. Sci. Nat. Trieste 28: 11-180 (page 144, Status as species)

- Narendra, A., Alkaladi, A., Raderschall, C.A., Robson, S.K.A., Ribi, W.A. 2013. Compound eye adaptations for diurnal and nocturnal lifestyle in the intertidal ant, Polyrhachis sokolova. PLoS ONE 8, e76015 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076015).

- Nielsen, J. S., M. G. Nielsen, C. F. Damgaard, and J. Offenberg. 2018. Experiences in Transplanting Wood Ants into Plantations for Integrated Pest Management. Sociobiology. 65:403-414. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v65i3.2872

- Nouhaud, P., Beresford, J., Kulmuni, J. 2022. Assembly of a hybrid Formica aquilonia × F. polyctena ant genome from a haploid male. Journal of Heredity 113(3), 353–359 (doi:10.1093/jhered/esac019).

- Nouhaud, P., Martin, S.H., Portinha, B., Sousa, V.C., Kulmuni, J. 2022. Rapid and predictable genome evolution across three hybrid ant populations. PLOS Biology, 2012, e3001914 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001914).

- Novgorodova, T. 2021. Preventing transmission of lethal disease: Removal behaviour of Lasius fuliginosus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Towards Fungus Contaminated Aphids. Insects 12, 99. (doi:10.3390/insects12020099).

- Novgorodova, T. A. 2015b. Organization of honeydew collection by foragers of different species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Effect of colony size and species specificity. European Journal of Entomology. 112:688-697. doi:10.14411/eje.2015.077

- Novgorodova, T.A., Biryukova, O.B. 2011. Some ethological aspects of the trophobiotic interrelations between ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and larvae of the sawfly Blasticotoma filiceti (Hymenoptera: Blasticotomidae), European Journal of Entomology 108, 47-52.

- Nygard, E. 2020. Thermal tolerance of two mound-building wood ants Formica aquilonia and Formica polyctena and their hybrids. Master's thesis, University of Helsinki.

- Nylander, W. 1856b. Synopsis des Formicides de France et d'Algérie. Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. (4) 5: 51-109 (page 60, Junior synonym of rufa)

- Oswalt, D.A. 2007. Nesting and foraging characteristics of the black carpenter ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus DeGeer (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ph.D. thesis, Clemson University.

- Pamilo, P., Kulmuni, J. 2022. Genetic identification of Formica rufa group species and their putative hybrids in northern Europe. Myrmecological News 32: 93-102 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_032:093).

- Pamilo, P., Sundström, L., Fortelius, W., Rosengren, R. 1994. Diploid males and colony-level selection in Formica ants. Ethology Ecology, Evolution 6, 221–235 (doi:10.1080/08927014.1994.9522996).

- Portinha, B., Avril, A., Bernasconi, C., Helanterä, H., Monaghan, J., Seifert, B., Sousa, V.C., Kulmuni, J., Nouhaud, P. 2021. Whole-genome analysis of multiple wood ant population pairs supports similar speciation histories, but different degrees of gene flow, across their European range. bioRxiv preprint (doi:10.1101/2021.03.10.434741).

- Pulliainen, U., Helantera, H., Sundstrom, L., Schultner, E. 2019. The possible role of ant larvae in the defence against social parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286: 20182867 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2867).

- Punttila, P., Kilpeläinen, J. 2009. Distribution of mound-building ant species (Formica spp., Hymenoptera) in Finland: preliminary results of a national survey. Annales Zoologici Fennici 46: 1–15.

- Putyatina, T.S., Gilev, A.V., Grinkov, V.G., Markov, A.V. 2022. Variation in the colour pattern of the narrow-headed ant Formica exsecta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in European Russia. European Journal of Entomology 119, 58-68 (doi:10.14411/eje.2022.006).

- Radchenko, A.G., Fisher, B.L., Esteves, F.A., Martynova, E.V., Bazhenova, T.N., Lasarenko, S.N. 2023. Ant type specimens (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the collection of Volodymyr Opanasovych Karawajew. Communication 1. Dorylinae, Poneromorpha and Pseudomyrmecinae. Zootaxa, 5244(1), 1–32 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5244.1.1).

- Rocha, F.H., Lachaud, J.-P., Hénaut, Y., Pozo, C., Pérez-Lachaud, G. 2020. Nest site selection during colony relocation in Yucatan Peninsula populations of the ponerine ants Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insects 11, 200 (doi:10.3390/insects11030200).

- Ruano, F., Lenoir, A., Silvestre, M., Khalil, A., Tinaut, A. 2018. Chemical profiles in Iberoformica subrufa and Formica frontalis, a new example of temporary host–parasite interaction. Insectes Sociaux 66, 223–233 (doi:10.1007/S00040-018-00677-6).

- Rybnikova, I. A. and A. V. Kuznetsov. 2015. Complexes of Formica s. str. nests in the Darwin Nature Reserve and causes of their degradation. Entomological Review. 95:947-952. doi:10.1134/s0013873815080023

- Schifani, E. (2022). The new checklist of the Italian fauna: Formicidae. Biogeographia – The Journal of Integrative Biogeography 37, ucl006 (doi:10.21426/b637155803).

- Schultner, E., Pulliainen, U. 2020. Brood recognition and discrimination in ants. Insectes Sociaux 67, 11–34 (doi:10.1007/s00040-019-00747-3).

- Seifert, B. 2021. A taxonomic revision of the Palaearctic members of the Formica rufa group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – the famous mound-building red wood ants. Myrmecological News 31: 133-179 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:133).

- Seifert, B., J. Kulmuni, and P. Pamilo. 2010. Independent hybrid populations of Formica polyctena X rufa wood ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) abound under conditions of forest fragmentation. Evol. Ecol. 24:1219-1237.

- Shang, Y., Feng, P., Wang, C. 2015. Fungi that infect insects: Altering host behavior and beyond. PLOS Pathogens 11, e1005037 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005037).

- Shrestha B, Tanaka E, Hyun MW, Han JG, Kim CS, Jo JW, Han SK, Oh J, Sung JM, Sung GH. 2017. Mycosphere Essay 19. Cordyceps species parasitizing hymenopteran and hemipteran insects. Mycosphere 8(9): 1424–1442 (DOI 10.5943/mycosphere/8/9/8).

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Siedlecki, I., Gorczak, M., Okrasińska, A., Wrzosek, M. 2021. Chance or necessity—The fungi co−occurring with Formica polyctena ants. Insects 12, 204 (doi:10.3390/insects12030204).

- Stitz, H. 1939. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meersteile nach ihren Merkmalen und nach ihrer Lebensweise. 37. Theil. Hautflüger oder Hymenoptera. I: Ameisen oder Formicidae. Jena: G. Fischer, 428 pp. (page 339, Variety/subspecies of rufa)

- Stukalyuk, S.V., Kozyr, M.S., Netsvetov, M.V., Zhuravlev, V.V. 2020. Effect of the invasive phanerophytes and associated aphids on the ant (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) assemblages. Halteres 11: 56-89 (doi:10.5281/ZENODO.4192900).

- Tsikas, A., Karanikola, P., Orfanoudakis, M. 2021. Influence of the red wood ant Formica lugubris Zetterstedt, (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on the surrounding forest soil. Bulgarian Journal of Soil Science 6: 9-17.

- van der Kooi, C.J., Stavenga, D.G., Arikawa, K., Belušič, G., Kelber, A. 2020. Evolution of insect color vision: From spectral sensitivity to visual ecology. Annual Review of Entomology 66, annurev-ento-061720–071644. (doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-061720-071644).

- Wagner, G.K., Staniec, B., Zagaja, M., Pietrykowska-Tudruj, E. 2020. First insight into detailed morphology of monotomids, with comments on chaetotaxy and life history based on myrmecophilous Monotoma angusticollis. Bulletin of Insectology 73 (1): 11-27.

- Wegnez, P. 2017. Découverte de Myrmica lobicornis Nylander, 1846 et Lasius jensi Seifert, 1982, deux nouvelles espèces pour le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie153, 46–49.

- Yarrow, I. H. H. 1955a. The British ants allied to Formica rufa L. (Hym., Formicidae). Trans. Soc. Br. Entomol. 12: 1-48 (page 3, Junior synonym of rufa)

- Zingg, S., P. Dolle, M. J. Voordouw, and M. Kern. 2018. The negative effect of wood ant presence on tick abundance. Parasites & Vectors. 11:9. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2712-0

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Alvarado M., and L. Galle. 2000. Ant assemblages associated with lowland forests in the southern part of the great Hungarian plain. Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientarum Hungaricae 46(2): 79-102.

- AntArea. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://antarea.fr/fourmi/

- Antarea (Personal Communication - Rumsais Blatrix- 27 April 2018)

- Antarea (at www.antarea.fr on June 11th 2017)

- Antonov I. A. 2012. Ant complexes of Baikalsk town. The Bulletin of Irkutsk State University 4: 143-146.

- Antonov I. A. 2013. Ant Assemblages (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Cities of the Temperate Zone of Eurasia. Russian Journal of Ecology 44(6): 523526.

- ArtDatabanken Bugs (via GBIG)

- Assing V. 1989. Die Ameisenfauna (Hym.: Formicidae) nordwestdeutscher Calluna-Heiden. Drosera 89: 49-62.

- Babik H., C. Czechowski, T. Wlodarczyk, and M. Sterzynska. 2009. How does a strip of clearing affect the forest community of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)? Fragmenta Faunistica 52(2): 125-141?

- Baroni Urbani C., and C. A. Collingwood. 1977. The zoogeography of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in Northern Europe. Acta Zoologica Fennica 152: 1-34.

- Barrett K. E. J. 1970. Ants in France, 1968-69. Entomologist 103: 270-274.

- Behr D., S. Lippke, and K. Colln. 1996. Zur kenntnis der ameisen von Koln (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Decheniana-Beihefte (Bonn) 35: 215-232.

- Bernard F. 1975. Rapports entre fourmis et vegetation pres des Gorges du Verdon. Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle de Nice 2: 57-79.

- Bernard F. 1976. Écologie des fourmis des grès d'Annot, comparées à celles de la Provence calcaire. Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle de Nice 3: 33-54.

- Beye, M., P. Neumann and R.F.A. Moritz. 1997. Nestmate recognition and the genetic gestalt in the mound-building ant Formica polyctena. Insectes Sociaux 44:49-58

- Bezdecka P. 1996. The ants of Slovakia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomofauna carpathica 8: 108-114.

- Blatrix R., C. Lebas, C. Galkowski, P. Wegnez, P. Pimenta, and D. Morichon. 2016. Vegetation cover and elevation drive diversity and composition of ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Mediterranean ecosystem. – Myrmecological News 22: 119-127.

- Boer P. 2019. Species list of the Netherlands. Accessed on January 22 2019 at http://www.nlmieren.nl/websitepages/specieslist.html

- Boer P., W. Dekoninck, A. J. Van Loon, and F. Vankerkhoven. 2003. Lijst van mieren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) van Belgie en Nederland, hun Nederlandse namen en hun voorkomen. Entomologische Berichten (Amsterdam) 63: 54-58.

- Boer P., W. Dekoninck, A. J. van Loon, and F. Vankerkhoven. 2003. Lijst van mieren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) van Belgie en Nederland, hun Nederlandse namen en hun voorkomen. Entomologische Berichten 63(3): 54-57.

- Boer P., W. Dekoninck, A. J. van Loon, and F. Vankerkhoven. 2003. List of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Belgium and The Netherlands, their status and Dutch vernacular names. Entomologische Berichten 63 (3): 54-58.

- Boer P., and J. Noordijk. 2004. De ruige gaststeekmier Myrmica hirsuta nieuw voor Nederland (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ned. Faun. Meded. 20: 25-32.

- Borowiec L. 2014. Catalogue of ants of Europe, the Mediterranean Basin and adjacent regions (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Genus (Wroclaw) 25(1-2): 1-340.

- Borowiec L., and S. Salata. 2012. Ants of Greece - Checklist, comments and new faunistic data (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Genus 23(4): 461-563.

- Bracko G. 2007. Checklist of the ants of Slovenia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Natura Sloveniae 9: 15-24

- Bracko, G. 2006. Review of the ant fauna (Hymenoptera:Formicidae) of Croatia. Acta Entomologica Slovenica 14(2): 131-156.

- Casevitz-Weulersse J., and C. Galkowski. 2009. Liste actualisee des Fourmis de France (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 114: 475-510.

- Casevitz-Weulersse J., and M. Prost. 1991. Fourmis de la Côte-d'Or présentes dans les collections du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle de Dijon. Bulletin Scientifique de Bourgogne 44: 53-72.

- Ceballos, P., and G. Ronchetti. "Le formiche del gruppo Formica rufa sui Pirenei orientali spagnoli, nelle province di Lerida e Gerona." Memorie della Società Entomologica Italiana 45 (1966): 153-168.

- Cherix D., and S. Higashi. 1979. Distribution verticale des fourmis dans le Jura vaudois et recensement prelimaire des bourdons (Hymenoptera, Formicidae et Apidae). Bull. Soc. Vaud. Sc. Nat. 356(74): 315-324.

- Colindre L. 2015. Les fourmis en Picardie: bilan 2014 (Hymenoptera/ Formicidae). Entomologiste Picard 26, 15 pages.

- Colindre L. 2017. Richess et utilite du cortege de fourmis en foret d'Ermenonville, Oise, Region Hauts-de-France. Association des Entomologistes de Picardie. 19 pages.

- Collingwood C. A. 1971. A synopsis of the Formicidae of north Europe. Entomologist 104: 150-176

- Collingwood C.A. 1959. Scandinavian Ants. Entomol. Rec. 71: 78-83

- Collingwood C.A. 1961. Ants in Finland. Entomol. Rec. 73: 190-195

- Collingwood, C. A. 1974. A revised list of Norwegian ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Norsk Entomologisk Tidsskrift 21: 31-35.

- Collingwood, C. A.. "A provisional list of Iberian Formicidae with a key to the worker caste." EOS (Revista española de entomología) Nº LVII (1978): 65-95.

- Collingwood, C. A.. "The Formicidae (Hymenoptera) of Fennoscandia and Denmark." Fauna Entomologica Scandinavica 8 (1979): 1-174.

- Csosz S., B. Marko, K. Kiss, A. Tartally, and L. Galle. 2002. The ant fauna of the Ferto-Hansag National Park (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). In: Mahunka, S. (Ed.): The fauna of the Fert?-Hanság National Park. Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, pp. 617-629.

- Csősz S. and Markó, B. 2005. European ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the ant collection of the Natural History Museum of Sibiu (Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben), Romania II. Subfamily Formicinae. Annales Historico-Naturales Musei Nationalis Hungarici 97: 225-240.

- Csősz S., B. Markó, and L. Gallé. 2001. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Stana Valley (Romania): Evaluation of the effectiveness of a myrmecological survey. Entomologica Romanica 6:121-126.

- Csősz S., B. Markó, and L. Gallé. 2011. The myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Hungary: an updated checklist. North-Western Journal of Zoology 7: 55-62.

- Czechowski W., A. Radchenko, W. Czechowska and K. Vepsäläinen. 2012. The ants of Poland with reference to the myrmecofauna of Europe. Fauna Poloniae 4. Warsaw: Natura Optima Dux Foundation, 1-496 pp

- Czechowski W., and P. Douwes. 1996. Morphometric characteristics of Formica polyctena Foerst. and Formica rufa L. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the Gorce Mts; interspecific and intraspecific variations. Ann. Zool. (Warsaw) 46: 125-141.

- Dekoninck W., T. Parmentier, J. Casteels, P. Wegnez, and F. Vankerhoven. 2015. Recente waarnemingen van de glanzende gastmier Formicoxenus nitidulus (Nylander, 1846) in Vlaanderen (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 151: 15-17.

- Della Santa E. 1994. Guide pour l'identification des principales espèces de fourmis de Suisse. Miscellanea Faunistica Helvetiae 3: 1-124.

- Dewes E. 2005. Ameisenerfassung im Waldschutzgebiet Steinbachtal/Netzbachtal. Abh. Delattinia 31: 89-118.

- Dlussky G. M., and B. Pisarski. 1970. Formicidae aus der Mongolei. Ergebnisse der Mongolisch-Deutschen Biologischen Expeditionen seit 1962, Nr. 46. Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Museum in Berlin 46: 85-90.

- Dubovikoff D. A., and Z. M. Yusupov. 2018. Family Formicidae - Ants. In Belokobylskij S. A. and A. S. Lelej: Annotated catalogue of the Hymenoptera of Russia. Proceedingss of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences 6: 197-210.

- Entomological Society of Latvia. 2003. http://leb.daba.lv/Formicidae.htm (Accessed on December 1st 2013).

- Formidabel Database

- Frouz, J. 2000. The effect of nest moisture on daily temperature regime in the nests of Formica polyctena wood ants. Insectes Sociaux 47:229-235

- Frouz, J. and L. Finer. 2007. Diurnal and seasonal fluctuations in wood ant (Formica polyctena) nest temperature in two geographically distant populations along a south north gradient. Insectes Sociaux 54:251-259

- GRETIA. 2017. Bilan annuel de l'enquete sur la repartition des fourmis armoricaines. 23 pages.

- Gadeau de Kerville H. 1922. Materiaux pour la Faune des Hymenopteres de la Normandie. Bull. Soc. Amis Sc. Nat. Rouen 1916-1921, 1922: 217-225.

- Galle L. 1993. Data to the ant fauna of the Bukk (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Natural history of the national parks of Hungary 7: 445-448.

- Gallé L., B. Markó, K. Kiss, E. Kovács, H. Dürgő, K. Kőváry, and S. Csősz. 2005. Ant fauna of Tisza river basin (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). In: Gallé, L. (szerk.): Vegetation and Fauna of Tisza River Basin I. Tiscia Monograph Series 7; Szeged, pp. 149-197.

- Gaspar C., and C. Thirion. 1978. Modification des populations d'Hymenopteres sociaux dans les milieux anthropogenes. Memorabilia Zoologica 29: 61-77.

- Gaspare Charles. 1965. Étude myrmécologique d'une région naturelle de Belgique: la Famenne Survey des Fourmis de la Région (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Institut agronomique de l'Etat a' Gembloux. 32(4): 427-434.

- Gilev A. V., I. V. Kuzmin, V. A. Stolbov, and S. D. Sheikin. 2012. Materials on the fauna and ecology of ants (formicidae) Southern part of the Tyumen region. Tyumen State University Herald 6: 86-91.

- Glaser F. 2009. Die Ameisen des Fürstentums Liechtenstein. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Amtlicher Lehrmittelverlag, Vaduz, 2009 (Naturkundliche Forschung im Fürstentum Liechtenstein; Bd. 26).

- Gouraud C. 2015. Bilan de l’année 2014 : Atlas des fourmis de Loire-Atlantique (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Atlas des Formicidae de Loire-Atlantique, compte rendu de la première année d’étude (2014)

- Grzes I. M. 2009. Ant species richness and evenness increase along a metal pollution gradient in the Boles?aw zinc smelter area. Pedobiologia 53: 65-73.

- Guénard B., and R. R. Dunn. 2012. A checklist of the ants of China. Zootaxa 3558: 1-77.

- Gyllenstrand, N., P. Seppä and P. Pamilo. 2004. Genetic differentiation in sympatric wood ants,Formica rufaandF. polyctena . Insectes Sociaux 51(2):139-145

- Holecova M., M. Klesniakova, K. Holla, and A. Sestakova. 2017. Winter activity in scots pine canopies in Borska Nizina Lowland (SW Slovakia)

- Karaman M. G. 2011. A catalogue of the ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Montenegro. Podgorica: Catalogues 3, Volume 2, Montenegrin Academy of Sciences and Arts, 140 pp.

- Kofler A. 1995. Nachtrag zur Ameisenfauna Osttirols (Tirol, Österreich) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecologische Nachrichten 1: 14-25.

- Kvamme T. 1982. Atlas of the Formicidae of Norway (Hymenoptera: Aculeata). Insecta Norvegiae 2: 1-56.

- Kvamme T., and A. Wetas. 2010. Revidert liste over norske maur Inkludert dialektiske navn og forslag til nye norske navn og forslag til norske navn. Norsk institutt for skog og landskap, Ås. 127 pp

- Lapeva-Gjonova, L., V. Antonova, A. G. Radchenko, and M. Atanasova. "Catalogue of the ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Bulgaria." ZooKeys 62 (2010): 1-124.

- Lebas C., C. Galkowski, P. Wegnez, X. Espadaler, and R. Blatrix. 2015. The exceptional diversity of ants on mount Coronat (Pyrénées-Orientales), and Temnothorax gredosi(Hymenoptera, Formicidae) new to France. R.A.R.E., T. XXIV (1): 24 33

- Lenoir, L., J. Bengtsson and T. Persson. 2003. Effects of Formica Ants on Soil Fauna-Results from a Short-Term Exclusion and a Long-Term Natural Experiment. Oecologia 134(3):423-430

- Li Z.h. 2006. List of Chinese Insects. Volume 4. Sun Yat-sen University Press

- Livory A. 2003. Les fourmis de la Manche. L'Argiope 39: 25-49.

- Majzlan O., and P. Devan. 2009. Selected insect groups (Hymenoptera, Neuroptera, Mecoptera, Raphidioptera) of the Rokoš Massif (Strážovské vrchy Mts.). Rosalia (Nitra), 20, p. 63–70.

- Malozemova L. A. 1972. Ants of steppe forests, their distribution by habitats, and perspectives of their utilization for protection of forests (north Kazakhstan). [In Russian.]. Zoologicheskii Zhurnal 51: 57-68.

- Marko B. 1999. Contribution to the knowledge of the myrmecofauna of the River Somes valley. In: Sárkány-Kiss, A., Hamar, J. (szerk.): The Somes/Szamos River Valley. A study of the geography, hydrobiology and ecology of the river system and its environment. Tiscia Monograph Series 3, Szolnok-Szeged-Tîrgu Mure?, pp. 297-302.

- Markó B., B. Sipos, S. Csősz, K. Kiss, I. Boros, and L. Gallé. 2006. A comprehensive list of the ants of Romania (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecologische Nachrichten 9: 65-76.

- Martin, A.-J., A. Kuusik, M. Mänd, L. Metspalu and U. Tartes. 2004. Respiratory patterns in nurses of the red wood antFormica polyctena(Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux 51(1):62-66.

- Müller, G.. "Le formiche della Venezia Guilia e della Dalmazia." Bollettino della Società Adriatica di Scienze Naturali in Trieste 28 (1923): 11-180.

- Neumeyer R., and B. Seifert. 2005. Commented check list of free living ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) species of Switzerland. Bulletin de la Societe Entomologique Suisse 78: 1-17.

- Nielsen M. G. 2011. A check list of Danish ants and proposed common names. Ent. Meddr. 79: 13-18.

- Novgorodova T. A., A. S. Ryabinin. 2015. Trophobiotic associations between ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) and aphids (Hemiptera, Aphidomorpha) in South Zauralye. News of Saratov University. Chemistry Series, Biology, Ecology 2(15): 98-107.

- Ovazza M. 1950. Contribution à la connaissance des fourmis des Pyrénées-Orientales. Récoltes de J. Hamon Vie et Milieu 1: 93-94.

- Paraschivescu D. 1972. Fauna mirmecologica din zonele saline ale Romaniei. Studii si Cercetari de Biologie. Seria Zoologie 24: 489-495.

- Paraschivescu D. 1978. Elemente balcanice in mirmecofauna R. S. Romania. Nymphaea 6: 463- 474.

- Paukkunen J., and M. V. Kozlov. 2015. Stinging wasps, ants and bees (Hy menoptera: Aculeata) of the Murmansk region, Northwest Russia. — Entomol. Fennica. 26: 53–73.

- Pavlova N. S. 2014. To ant fauna (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of the floodplain of Medvedista River (Saratov Province). Entomological and parasitological studies in the Volga region 11: 145-147.

- Pech P. 2012. A contribution to the distribution and biology of Myrmica vandeli (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the Czech Republic. Silva Gabreta 18(2): 95-99.

- Petrov I. Z., and C. A. Collingwood. 1992. Survey of the myrmecofauna (Formicidae, Hymenoptera) of Yugoslavia. Archives of Biological Sciences (Belgrade) 44: 79-91.

- Pusvaskyte O. 1979. Myrmecofauna of the Lituanian SSR. Acta Entomologica Lituanica 4: 99-105.

- Radchenko A. G. 2007. The ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the collection of William Nylander. Fragmenta Faunistica (Warsaw) 50: 27-41.

- Ran H., and S. Y. Zhou. 2012. Checklist of chinese ants: formicomorph subfamilies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) II. Journal of Guangxi Normal University: Natural Science Edition 30(4): 81-91.

- Reznikova Z. I. 2003. Distribution patterns of ants in different natural zones and landscapes in Kazakhstan and West Siberia along a meridian trend. Euroasian Entomological Journal 2(4): 235-342.

- Rzeszowski K., H. Babik, W. Czechowski, and B. Marko. 2013. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Chelmowa Gora in the Swietokrzyski National Park. Fragmenta Faunistica 56(1): 1-15.

- Salata S. 2014. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the National Park of the Stołowe Mts. Przyroda Sudetow 17: 161-172.

- Saure C. 2005. Rote Liste und Gesamtartenliste der Bienen und Wespen (Hymenoptera part.) von Berlin mit Angaben zu den Ameisen. In: DER LANDESBEAUFTRAGTE FÜR NATURSCHUTZ UND LANDSCHAFTSPFLEGE / SENATSVERWALTUNG FÜR STADTENTWICKLUNG (Hrsg.): Rote Listen der gefährdeten Pflanzen und Tiere von Berlin. CD-ROM.

- Schlick-Steiner B. C., and F. M. Steiner. 1999. Faunistisch-ökologische Untersuchungen an den freilebenden Ameisen (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Wiens. Myrmecologische Nachrichten 3: 9-53.

- Seifert B. 1994. Die freilebenden Ameisenarten Deutschlands (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) und Angaben zu deren Taxonomie und Verbreitung. Abhandlungen und Berichte des Naturkundemuseums Görlitz 67(3): 1-44.

- Seifert B. 1998. Rote Liste der Ameisen. - in: M. Binot, R. Bless, P. Boye, H. Gruttke und P. Pretscher: Rote Liste gefährdeter Tiere Deutschlands. Bonn-Bad Godesberg 1998: 130-133.

- Siberian Zoological Museum. Website available at http://szmn.sbras.ru/old/Hymenop/Formicid.htm. Accessed on January 27th 2014.

- Sonnenburg H. 2005. Die Ameisenfauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Niedersachsens und Bremens. Braunschweiger Naturkundliche Schriften 7: 377-441.

- Steiner F. M., S. Schödl, and B. C. Schlick-Steiner. 2002. Liste der Ameisen Österreichs (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), Stand Oktober 2002. Beiträge zur Entomofaunistik 3: 17-25.

- Stiprais M. 1973. Materi?li par R?gas kukai?u faunu. - Latvijas Entomologs, 15: 30-32.

- Stroo A. 2003. Het ruggengraatloze soortnbeleid. Nieuwsbrief European Invertebrate Survey Nederland 36: 8-14.

- Stukalyuk S. V. 2015. Structure of the ant assemblages (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the broad-leaved forests of Kiev. Entomological Review 95(3): 370–387.

- Suvak M. 2013. First record of Formica fennica Seifert, 2000 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in Norway. Norwegian Journal of Entomology 60: 73–80.

- Tausan I., M. M. Jerpel, I. R. Puscasu, C. Sadeanu, R. E. Brutatu, L. A. Radutiu, and V. Giurescu. 2012. Ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Sibiu County (Transylvania, Romania). Brukenthal. Acta Musei 7(3): 499-520.

- Tizado Morales, E. J.. Estudio comparado de la fauna y la biología de pulgones (Hom.), afidíinos (Hym.) y otros insectos acompañantes en dos áreas de la provincia de León In Secretariado de Publicaciones, Tesis doctoral en microficha, nº 67. León: Universidad de León, 1991.

- Vepsalainen K., H. Ikonene, and M. J. Koivula. 2008. The structure of ant assembalges in an urban area of Helsinki, southern Finland. Ann. Zool. Fennici 45: 109-127.

- Véle, A. and J. Holua. 2008. Impact of vegetation removal on the temperature and moisture content of red wood ant nests. Insectes Sociaux 55(4): 364-369.

- Wegnez P. 2014. Premières captures de Lasius distinguendus Emery, 1916 et de Temnothorax albipennis (Curtis, 1854) au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (Hymenoptera : Formicidae). Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 150 (2014) : 168-171.

- Wegnez P. 2017. Découverte de Myrmica lobicornis Nylander, 1846 et Lasius jensi Seifert, 1982, deux nouvelles espèces pour le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 153: 46-49.

- Wegnez P. 2018. Premières decouvertes de Myrmica bibikoffi Kutter, 1963 et de Ponera testacea Emery, 1895, au Luxembourg (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 154: 263–272.

- Wegnez P., and F. Mourey. 2016. Formica uralensis Ruzsky, 1895 une espèce encore présente en France mais pour combien de temps ? (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 152: 72-80.

- Wegnez P., and M. Fichaux. 2015. Liste actualisee des especes de fourmis repertoriees au Grand-Duche de Luxembourg (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 151: 150-165

- Wiezik M. 2007. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of mountain and alpine ecosystems at Southern part of Krá?ovoho?ské Tatry Mts. Naturae Tutela 11: 85-90.

- Wu wei, Li Xiao Mei, Guo Hong. 2004. A primary study on the fauna of Formicidae in Urumqi and its vicinities. Arid Zone Research 21(2): 179-182

- Zryanin V. A., and T. A. Zryanina. 2007. New data on the ant fauna Hymenoptera, Formicidae in the middle Volga River Basin. Uspekhi Sovremennoi Biologii 127(2): 226-240.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Polygynous

- Supercolonies

- Temporary parasite

- Diploid male

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- Nesting Notes

- Labial gland disease Associate

- Host of unknown agent

- Ant Associate

- Host of Formica (Serviformica) species

- Host of Formica sanguinea

- Host of Formica truncorum

- Host of Formicoxenus nitidulus

- Beetle Associate

- Host of Monotoma angusticollis (Coleopotera: Monotomidae)

- Nematode Associate

- Host of Oscheius dolichura

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis brohmeri

- Host of Aphis craccivora

- Host of Aphis evonymi

- Host of Aphis fabae

- Host of Aphis jacobaeae

- Host of Aphis pomi

- Host of Aphis subnitidae

- Host of Callipterinella tuberculata

- Host of Chaitophorus albitorosus

- Host of Chaitophorus albus

- Host of Chaitophorus populeti

- Host of Chaitophorus populialbae

- Host of Chaitophorus salicti

- Host of Cinara boerneri

- Host of Cinara laricis

- Host of Cinara piceae

- Host of Cinara pinea

- Host of Cinara pini

- Host of Glyphina betulae

- Host of Macrosiphoniella pulvera

- Host of Rhopalosiphum padi

- Host of Schizaphis gramina

- Host of Schizaphis pyri

- Host of Symydobius oblongus

- Trematode Associate

- Host of Dicrocoelium dendriticum

- Fungus Associate