Linepithema humile

| Linepithema humile | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Dolichoderinae |

| Tribe: | Leptomyrmecini |

| Genus: | Linepithema |

| Species: | L. humile |

| Binomial name | |

| Linepithema humile (Mayr, 1868) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Argentine Ant | |

| Language: | English |

| Aruzenchin-ari | |

| Language: | Japanese |

This is the notoriously pestiferous Argentine ant, one of the 100 worst invasive species in the world (IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group). Its colonies are large and polygynous, sometimes comprising hundreds of queens and many thousands of workers. New nests are founded by migration or budding. The Argentine ant commonly infests houses and other premises, contaminating and spoiling stored food and other products. It tends homopterous agricultural and horticultural insect pests, and severely damages and depletes populations of native ant species in infested areas. L. humile is native to parts of South America (Brazil and Argentine) and has been distributed throughout much of the world by human commerce.

| At a Glance | • Highly invasive • Supercolonies • Polygynous |

Photo Gallery

Identification

Worker Eyes large (OI > 30); antennal scapes long (SI > 105); pronotum and first two gastric tergites lacking erect setae; mesopleura and metapleura densely pubescent.

Workers of the sister species Linepithema oblongum, from the high Andes of Bolivia and northern Argentina, normally have at least some members of each series with dilute pubescence on gastric tergites 2–4. These ants also have, on average, smaller eyes (OI 28–38) and longer antennal scapes (SI 120–139) than L. humile. Workers of Linepithema anathema, a rarely-collected Brazilian species, have a more produced propodeum, a narrow head (CI < 86), and usually bear short standing setae on gastric tergites 1–2. Workers of other Humile-group species have shorter antennal scapes and often bear erect setae on the pronotum and basal gastric tergites. Males of related species are much smaller than L. humile and lack the greatly swollen mesosoma.

Male Forewing with single submarginal cell; mesosoma robust (MML > 1.3), mesoscutum greatly enlarged and overhanging pronotum; wings short relative to mesosomal length (WI < 21).

Keys including this Species

- Key to Linepithema workers

- Key to Linepithema males

- Key to the Dolichoderinae genera of the southwestern Australian Botanical Province

- Key to Linepithema of Columbia

- Clave para Linepithema en Colombia

Distribution

Native to the Paraná river drainage of Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, and Uruguay. Introduced worldwide.

This introduced species occurs sporadically throughout Florida, in places forming massive populations. It occurs in both moist and dry open habitats, usually in heavily disturbed sites. Pest status: can become a nuisance by sheer numbers, trailing long distances to outdoor eating areas and into buildings. First published Florida record: Wheeler 1932; earlier specimens: 1914. (Deyrup, Davis & Cover, 2000.)

Linepithema humile was previously reported in Colombia (Sanabria & Chacón de Ulloa 2009; Wild 2004, 2007). However, we found that the specimens identified as L. humile in Sanabria & Chacón de Ulloa (2009), and many other “Linepithema humile” specimens in Colombian entomological collections, were misidentified. In most cases these specimens were Linepithema piliferum or Linepithema neotropicum, and in no cases were L. humile. In order to confirm the occurrence of L. humile in Colombia (Wild 2007), we studied the L. humile specimens reported in Wild (2007) and deposited in WPMC. We confirm that the specimens are L. humile, and this remains the only known collection of the species in Colombia. These ants were collected in the Colombian coffee zone (Armenia, Quindio) in 1973, but despite subsequent intensive sampling done in that area by the program Paisajes Rurales (Instituto Alexander von Humboldt), there are no more L. humile records from Armenia or elsewhere. Thus it is possible that this was an introduction that did not persist and the species no longer occurs in Colombia. (Escarraga & Guerrero, 2016)

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 25.68015° to -37.533333°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Afrotropical Region: Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Saint Helena, United Arab Emirates.

Australasian Region: Australia, New Zealand, Norfolk Island.

Indo-Australian Region: Hawaii, Vanuatu.

Malagasy Region: Réunion.

Nearctic Region: United States.

Neotropical Region: Argentina (type locality), Bermuda, Brazil, Ecuador, French Guiana, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay.

Palaearctic Region: Balearic Islands, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canary Islands, Channel Islands, Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Iberian Peninsula, Iran, Italy, Japan, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Türkiye, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

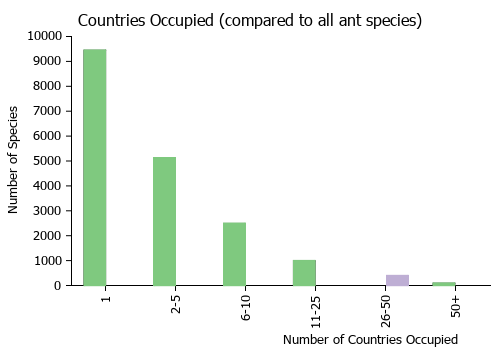

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

There is an Antwiki webpage with a list of some recent studies of the Argentine ant.

Wild (2007) - This important pest species has a literature too extensive to be covered in depth here. An early general review of the biology of this ant is given by Newell and Barber (1913). The spread of Argentine ants around the world is documented by Roura-Pascual et al. (2004), Wild (2004), Giraud et al. (2002), and Suarez et al. (2001). Ecological impacts of Argentine ant invasion have been detailed in numerous studies, including Suarez and Case (2003), Touyama et al. (2003), Christian (2001), and Human and Gordon (1997). Colony structure has also received considerable attention, and relevant papers include Holway and Suarez (2004), Tsutsui and Case (2001), Reuter et al. (2001), and Kreiger and Keller (2000). A series of studies by Cavill and colleagues (Cavill and Houghton 1973, Cavill and Houghton 1974, Cavill et al. 1980) describe some of the glandular and cuticular chemistry of L. humile. Chemical and biological control options are reviewed by Harris (2002).

Of the L. humile material examined, more than 90% of native range records are within 10 kilometers of a major river in the Paraná drainage. Contrary to some reports (Buczkowski et al. 2004), L. humile can reach high densities in urban areas in Argentina and Paraguay (Wild 2004) as well as in less disturbed habitats (Heller 2004). Where nest information was recorded in the native range, 24 nests are from soil, five from under covering objects such as stones or garbage, one from an old termite mound, and one from under bark. This species is polygynous and polydomous, and many nests are recorded as having numerous dealate queens. In contrast to introduced populations, alate queens are not uncommon in nests in Argentina (Wild 2004). One observation in Victoria, Argentina, notes a live lycaenid larva in the brood nest (Wild, pers. obs.).

This ant forms what has been called supercolonies: a large number of nests spread over large areas where the individuals from one nest can be brought to any other nest and accepted as nestmates (Corin et al., 2007). Linepithema humile do not have nuptial flights (Passera and Keller 1990). Queens mate with related males in their natal nests (Markin 1970).

Inou et al. (2015) suggested the results of a genetic study of four supercolonies in Kobe Japan showed that these colonies replaced their queens during the reproductive season. Genetic differentiation among workers varied significantly in comparing May samples to September samples. They feel this provides evidence for queen execution, which has been reported in two introduced populations (USA, Markin 1970 and France Keller et al. 1989).

Bertelsmeier et al. (2015a, b) examined elements of interspecific aggression, and food resource discovery and dominance, between this species and several other highly invasive ants. In laboratory assays Linepithema humile was highly aggressive when confronted with workers of other invasive ants. Of the group of four species that were found to be aggressive, L. humile was found to be fairly adept at finding and recruiting to food in a laboratory arena experiment.

Regional Notes

Brazil - DaRocha et al. (2015) studied the diversity of ants found in bromeliads of a single large tree of Erythrina, a common cocoa shade tree, at an agricultural research center in Ilhéus, Brazil. Forty-seven species of ants were found in 36 of 52 the bromeliads examined. Bromeliads with suspended soil and those that were larger had higher ant diversity. Linepithema humile was found in a single bromeliad and was associated with the suspended soil and litter of the plant.

Canary Islands - Espadaler (2007): The Argentine ant is known from all the Canary Islands (Espadaler & Bernal, 2003). At El Hierro it occupies habitats from next to sea level to one thousand meters, in pine forests. Confronted with the two populations known to exist in North Mediterranean Europe (Giraud et al., 2002), the Argentine ants from El Hierro showed aggressiveness towards the “Catalan” population and reacted peacefully towards the “Main” population from mainland Europe. Aggression tests (one to one worker; five replicates) were run with two samples from El Hierro (La Frontera; Mirador de las Playas). I conclude that both samples from El Hierro belong to the genotypic profile of the “Main” population, the more abundant in Western Mediterranean Europe.

Europe - Collingwood (1979): This species was introduced into Europe from South America and has become an established and notorious pest in the Mediterranean area, developing very populous multi-queened colonies along the coast. It is sometimes brought into North Europe with plant materials and occasionally colonises heated premises. It does not appear to be able to establish outside in northern latitudes but is present and said to be increasing in the Channel Islands.

Greece Borowiec and Salata (2022) - Noted only from tourist resorts. Ants were collected on ground in botanical garden, grassland and small garden in urban area.

New Zealand: Corin, Abbott et al. (2007) found that the introduced population of Linepithema humile in New Zealand effectively forms a single unicolonial population, a supercolony, which is likely the result of colonization from a single source population from Australia (Corin, Lester et al., 2007).

Flight Period

| X | X | X | |||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Diptera

- This species is a host for the phorid fly Apocephalus silvestrii (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the phorid fly Ceratoconus setipennis (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the phorid fly Pseudacteon pusillus (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a prey for the syrphid fly Mixogaster lanei (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

Hemiptera

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis coreopsidis (a trophobiont) (Altfeld and Stiling, 2009; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis gossypii (a trophobiont) (Powell and Silverman, 2010; Tena et al., 2013; LeVan and Holway, 2015; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis nerii (a trophobiont) (Bristow, 1991; Pringle et al., 2014; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis spiraecola (a trophobiont) (Tena et al., 2013; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Chaitophorus populicola (a trophobiont) (Mondor and Addicott, 2007; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Myzus persicae (a trophobiont) (Powell and Silverman, 2010; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

Hymenoptera

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Basalys sp. (a parasite) in Argentina (Loiacono, 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2016).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Trichopria sp. (a parasite) in Argentina (Loiacono, 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2016).

- This species is a host for the aphelinid wasp Aphytis melinus (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the aphelinid wasp Cales noacki (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the aphelinid wasp Eretmocerus sp. (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the encyrtid wasp Comperiella bifasciata (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the encyrtid wasp Leptomastix dactylopii (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the encyrtid wasp Metaphycus anneckei (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the encyrtid wasp Metaphycus hageni (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the encyrtid wasp Metaphycus lounsburyi (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a associate (details unknown) for the encyrtid wasp Ananusia longiscapus (a associate (details unknown)) (Quevillon, 2018) (as Iridomyrmex domestica).

- This species is a associate (details unknown) for the encyrtid wasp Comperiella bifasciata (a associate (details unknown)) (Quevillon, 2018).

Lepidoptera

- This ant has been observed tending larvae of Lampides boeticus (Obregon et al. 2015).

Predators

- Pekár et al. (2018) - In the Iberian Penisula, this ant is preyed upon by a spider species in the genus Zodarion sp. (Araneae: Zodariidae). All members of this genus are specialized ant predators that exclusively prey on ants.

Nematodes

- This species is a host for the nematode Diploscapter lycostoma (a parasite) (Markin & McCoy, 1968).

Virus

- This species is a host for the virus Aparavirus: Kashmir bee virus (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

- This species is a host for the virus Iflavirus: Deformed wing virus (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

- This species is a host for the virus Linepithema humile virus-1 (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

- This species is a host for the virus Triatovirus: Black queen cell virus (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

Genetics

Linepithema humile has had their entire genome sequenced.

Palomeque et al. (2015) found class II mariner elements, a form of transposable elements, in the genome of this ant.

Life History Traits

- Queen number: polygynous (Bartels, 1983; Newell & Barber, 1913; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

- Colony type: supercolony

- Foraging behaviour: mass recruiter

Castes

Queens differ in their Cuticular Hydrocarbons according to ovarian activity. Whereas the cuticular profile of non-laying queens is similar to that of sterile workers, it gradually changes both qualitatively and quantitatively once queens start to lay eggs. These changes are independent of mating status, since virgin egg-laying queens show a CH profile similar to that of mated egg-laying queens (de Biseau et al. 2004).

Images from AntWeb

Worker

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0006019. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0006020. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0104147. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0106983. Photographer Alexander Wild, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ALWC, Alex L. Wild Collection. |

Queen

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0104070. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- humile. Hypoclinea humilis Mayr, 1868b: 164 (w.) ARGENTINA. Forel, 1908c: 395 (m.); Newell, 1908: 28 (q.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1951: 186 (l.); Crozier, 1969: 250 (k.). Combination in H. (Iridomyrmex): Mayr, 1870b: 959; in Iridomyrmex: Emery, 1888d: 386; in Linepithema: Shattuck, 1992a: 16. Senior synonym of arrogans, riograndensis: Wild, 2004: 1207. See also: Gallardo, 1916a: 97; Bernard, 1967: 251; Collingwood, 1979: 33; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1418; Ward, 1987: 1; Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1990a: 465; Shattuck, 1994: 123; Wild, 2007a: 61; Solis, Fox, Rossi & Bueno, 2010: 19.

- arrogans. Iridomyrmex humilis var. arrogans Chopard, 1921: 237 (footnote),:241, figs. 1-31 (w.q.m.l.) FRANCE. [Also described as new by Santschi, 1929d: 306 (in key).] Combination in Linepithema: Shattuck, 1992a: 16. Junior synonym of humile: Bernard, 1967: 251. Revived from synonymy as subspecies of humile: Shattuck, 1992a: 16. Junior synonym of humile: Wild, 2004: 1207.

- riograndensis. Iridomyrmex riograndensis Borgmeier, 1928b: 64 (w.) BRAZIL. Combination in Linepithema: Shattuck, 1992a: 16. Junior synonym of humile: Wild, 2004: 1207.

Type Material

- Hypoclinea (Iridomyrmex) humilis: Holotype, worker, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna.

Taxonomic Notes

The taxonomy and distribution of L. humile was reviewed in depth by Wild (2004). The following description is from Wild (2007):

Description

Worker

Holotype: HL 0.74, HW 0.66, MFC 0.16, SL 0.76, FL 0.65, LHT 0.68, PW 0.45, ES 2.93, SI 115, CI 89, CDI 24, OI 40.

Worker: (n = 81) HL 0.62–0.78, HW 0.53–0.72, MFC 0.14–0.18, SL 0.62–0.80, FL 0.52–0.68, LHT 0.57–0.76, PW 0.35–0.47, ES 1.98–3.82, SI 108–126, CI 84–93, CDI 23–28, OI 32–49.

Head in full face view longer than broad (CI 84–93), narrowed anteriorly and reaching its widest point just posterior to compound eyes. Lateral margins broadly convex, grading smoothly into posterior margin. Posterior margin straight in smaller workers to weakly concave in larger workers. Compound eyes large (OI 32–49), comprising 82–110 ommatidia (normally around 100). Antennal scapes long (SI 108–126), as long or slightly longer than HL and easily surpassing posterior margin of the head in full face view. Frontal carinae narrowly to moderately spaced (CDI 23–28). Maxillary palps relatively short, shorter than ½ HL, ultimate segment (segment six) noticeably shorter than segment 2.

Pronotum and mesonotum forming a continuous convexity in lateral view, mesonotal dorsum nearly straight, not angular or strongly impressed, although sometimes with a slight impression in anterior portion. Metanotal groove moderately impressed. Propodeum in lateral view inclined anteriad. In lateral view, dorsal propodeal face meeting declivity in a distinct though obtuse angle, from which the declivity descends in a straight line to the level of the propodeal spiracle.

Petiolar scale sharp and inclined anteriorly, in lateral view falling short of the propodeal spiracle.

Dorsum of head (excluding clypeus), mesosoma, petiole, and gastric tergites 1–2 ( = abdominal tergites 3–4) devoid of erect setae (very rarely with a pair of small setae on gastric tergite 2). Gastric tergites 3–4 each bearing a pair of long, erect setae. Venter of metasoma with scattered erect setae.

Integument shagreened and lightly shining. Body and appendages including gula, entire mesopleura, metapleura, and abdominal tergites covered in dense pubescence.

Body and appendages concolorous, most commonly a medium reddish or yellowish brown but ranging in some populations from testaceous to dark brown, never yellow or piceous.

Queen

(n = 13) HL 0.83–0.92, HW 0.83–0.93, SL 0.81–0.89, FL 0.78–0.90, LHT 0.88–0.97, EL 0.31–0.36, MML 1.67–2.09, WL 4.42–4.51, CI 93–101, SI 96–102, OI 36–39, WI 24–27, FI 40–48.

Moderately large species (MML 1.67–2.09). Head slightly longer than broad to as broad as long in full face view (CI 93–101), posterior margin slightly concave to slightly convex. Eyes of moderate size (OI 36–39). Ocelli small. Antennal scapes relatively long (SI 96–102), in full face view scapes in repose surpassing posterior margin by a length greater than length of first funicular segment.

Forewings short relative to mesosomal length (WI 24–27). Forewings with Rs+M at least three times longer than M.f2. Legs of moderate length relative to mesosomal length (FI 40–48).

Dorsum of mesosoma and metasoma with scattered standing setae. Mesoscutum bearing 2–11 standing setae. Body color medium reddish brown. Antennal scapes, legs, and mandibles concolorous with body.

Male

(n = 12) HL 0.56–0.70, HW 0.56–0.74, SL 0.13–0.16, FL 0.60–0.77, LHT 0.51–0.66, EL 0.31–0.34, MML 1.40–1.96, WL 2.55–3.26, PH 0.25–0.34, CI 99–106, SI 22–27, OI 51–55, WI 17–20, FI 37–45.

Head about as broad as long in full face view (CI 99–106). Eyes large (OI 51–55), occupying much of anterolateral surface of head and separated from posterolateral clypeal margin by a length less than width of antennal scape. Ocelli large and in full frontal view set above adjoining posterolateral margins. Antennal scape of moderate length (SI 22–27), about 2/3 length of 3rd antennal segment. Anterior clypeal margin straight to broadly convex. Mandibles small, bearing a single apical tooth and 4-8 denticles along masticatory margin and rounding into inner margin. Masticatory margin relatively short, subequal in length to inner margin. Inner margin roughly parallel to, or converging distally with, exterior lateral margin.

Mesosoma unusually well developed, considerably wider than head width, and larger in bulk and in length than metasoma. Mesoscutum greatly enlarged, projecting forward in a convexity overhanging pronotum. Scutellum large, convex, nearly as tall as mesoscutum and projecting well above level of propodeum. Propodeum well developed and overhanging petiolar node, posterior propodeal face strongly concave. Forewings short relative to mesosomal length (WI 17–20) and bearing a single submarginal cell. Wing color whitish or yellowish with dark brown veins and stigma. Legs short relative to mesosoma length (FI 37–45).

Petiolar scale taller than node length and bearing a broad crest. Ventral process well developed. Gaster oval in dorsal view, nearly twice as long as broad. Gonostylus produced as a bluntly rounded pilose lobe. Volsella with cuspis present, digitus short and downturned distally.

Dorsal surfaces of body largely devoid of erect setae, occasionally with a few fine, short setae scattered on mesoscutum, scutellum, and posterior abdominal tergites. Venter of gaster with scattered setae. Pubescence dense on body and appendages, becoming sparse only on medial propodeal dorsum.

Color as for worker.

Worker Morphology

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- Caste: monomorphic

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- n = 8, 2n = 16 (Australia; Spain) (Crozier, 1968a; Crozier, 1975; Lorite et al., 1996b; Lorite et al., 1998b) (as Iridomyrmex humilis).

References

- Abril, S., Diaz, M., Enriquez, M.L. & Gomez, C. 2013. More and bigger queens: a clue to the invasive success of the Argentine ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in natural habitats. Myrmecological News 18, 19-24.

- Abril, S., Gómez, C. 2019. Factors triggering queen executions in the Argentine ant. Scientific Reports 9: 10427 (doi:10.1038/S41598-019-46972-5).

- Abril, S., Oliveras, J., Gomez, C. 2007. Foraging Activity and Dietary Spectrum of the Argentine Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Invaded Natural Areas of the Northeast Iberian Peninsula. Environmental Entomology 36(5): 1166-1173.

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Albrecht, M. 1995. New species distributions of ants in Oklahoma, including a South American invader. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 75: 21-24 (page 21, record in Oklahoma)

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Alvarez-Blanco, P., Broggi, J., Cerdá, X., González-Jarri, O., Angulo, E. 2020. Breeding consequences for a songbird nesting in Argentine ant’ invaded land. Biological Invasions 22, 2883–2898. (doi:10.1007/S10530-020-02297-3).

- Alvarez‐Blanco, P., Cerdá, X., Hefetz, A., Boulay, R., Bertó‐Moran, A., Díaz‐Paniagua, C., Lenoir, A., Billen, J., Liedtke, H.C., Chauhan, K.R., Bhagavathy, G., Angulo, E. 2020. Effects of the Argentine ant venom on terrestrial amphibians. Conservation Biology 35, 216–226 (doi:10.1111/cobi.13604).

- Arcos, J., Chaves, D., Alarcón, P., Rosado, A. 2022. First record of Temnothorax convexus (Forel, 1894) in Portugal (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with an updated checklist of the ants from the country. Sociobiology, 69(2), e7623 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v69i2.7623).

- Arcos, J., Chaves, D., Alarcón, P., Rosado, Á. 2022. First record of Temnothorax convexus (Forel, 1894) in Portugal (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with an updated checklist of the ants from the country. Sociobiology, 692), e7623 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v69i2.7623).

- Arnan, X., Angulo, E., Boulay, R., Molowny-Horas, R., Cerdá, X., Retana, J. 2021. Introduced ant species occupy empty climatic niches in Europe. Scientific Reports 11, 3280 (doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82982-y).

- Arnan, X., Cerdá, X., Retana, J. 2012. Distinctive life traits and distribution along environmental gradients of dominant and subordinate Mediterranean ant species. Oecologia 170, 489–500 (doi:10.1007/s00442-012-2315-y).

- Azevedo Filho, P.A.de, Vasconcelos, F.R., Santos, R.C.G.dos, Morais, S.M.de. 2021. Cuticular hydrocarbons from ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Odontomachus bauri (Emery) from the tropical forest of Maranguape, Ceará, Brazil. Research, Society and Development 10, e13010817119 (doi:10.33448/rsd-v10i8.17119).

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Baty, J.W., Bulgarella, M., Dobelmann, J., Felden, A., Lester, P.J. 2020. Viruses and their effects in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 30: 213-228 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:213).

- Bernard, F. 1967a [1968]. Faune de l'Europe et du Bassin Méditerranéen. 3. Les fourmis (Hymenoptera Formicidae) d'Europe occidentale et septentrionale. Paris: Masson, 411 pp. (page 251, see also)

- Bertelsmeier, C. 2021. Globalization and the anthropogenic spread of invasive social insects. Current Opinion in Insect Science 46, 16–23. (doi:10.1016/j.cois.2021.01.006).

- Bertelsmeier, C., A. Avril, O. Blight, A. Confais, L. Diez, H. Jourdan, J. Orivel, N. St Germes, and F. Courchamp. 2015a. Different behavioural strategies among seven highly invasive ant species. Biological Invasions. 17:2491-2503. doi:10.1007/s10530-015-0892-5

- Bertelsmeier, C., A. Avril, O. Blight, H. Jourdan, and F. Courchamp. 2015b. Discovery-dominance trade-off among widespread invasive ant species. Ecology and Evolution. 5:2673-2683. doi:10.1002/ece3.1542

- Berville, L., Hefetz, A., Espadaler, X., Lenior, A., Renuuci, M., Blight, O., Provost, E. 2013. Differentiation of the ant genus Tapinoma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Mediterranean Basin by species-specific cuticular hydrocarbon profiles. Myrmecological News 18: 77-92.

- Billen, J.P.J. 2019. Diversidad y morfología de las glándulas exocrinas en las hormigas. Pp. 165-174 in: Fernández, F., Guerrero, R.J., Delsinne, T. (eds.) 2019d. Hormigas de Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1198 pp.

- Borowiec, L. 2014. Catalogue of ants of Europe, the Mediterranean Basin and adjacent regions (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Genus (Wroclaw) 25(1-2): 1-340.

- Borowiec, L., Salata, S. 2022. A monographic review of ants of Greece (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Vol. 1. Introduction and review of all subfamilies except the subfamily Myrmicinae. Part 1: text. Natural History Monographs of the Upper Silesian Museum 1: 1-297.

- Borowiec, M.L. 2019. Convergent evolution of the army ant syndrome and congruence in big-data phylogenetics. Systematic Biology 68, 642–656 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy088).

- Borowiec, M.L., Moreau, C.S., Rabeling, C. 2020. Ants: Phylogeny and Classification. In: C. Starr (ed.), Encyclopedia of Social Insects (doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90306-4_155-1).

- Branstetter, M.G., Danforth, B.N., Pitts, J.P., Faircloth, B.C., Ward, P.S., Buffington, M.L., Gates, M.W., Kula, R.R., Brady, S.G. 2017. Phylogenomic insights into the evolution of stinging wasps and the origins of ants and bees. Current Biology 27, 1019–1025 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.027).

- Brown, B., Hash, J., Hartop, E., Porras, W., Amorim, D. 2017. Baby Killers: Documentation and Evolution of Scuttle Fly (Diptera: Phoridae) Parasitism of Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Brood. Biodiversity Data Journal 5, e11277. (doi:10.3897/bdj.5.e11277).

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Burford, B.P., Lee, G., Friedman, D.A., Brachmann, E., Khan, R., MacArthur-Waltz, D.J., McCarty, A.D., Gordon, D.M. 2018. Foraging behavior and locomotion of the invasive Argentine ant from winter aggregations. PLOS ONE 13, e0202117 (doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0202117).

- Cantone S. 2017. Winged Ants, The Male, Dichotomous key to genera of winged male ants in the World, Behavioral ecology of mating flight (self-published).

- Cantone S. 2018. Winged Ants, The queen. Dichotomous key to genera of winged female ants in the World. The Wings of Ants: morphological and systematic relationships (self-published).

- Cantone, S., Di Giulio, A. 2023. A new Neotropical ant species of genus Linepithema Mayr (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Dolichoderinae) with partial revision of the L. fuscum group based on males. ZooKeys 1160, 125–144 (doi:10.3897/zookeys.1160.95694).

- Cantone, S., Von Zuben, C.J. 2019. The hindwings of ants: A phylogenetic analysis. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2019, 1–11 (doi:10.1155/2019/7929717).

- Carroll, T.M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). M.S. thesis, Purdue University.

- Castañeda, I., Bonnaud, E., Courchamp, F., Luque, G. 2021. Influence of the Number of Queens on Nest Establishment: Native and Invasive Ant Species. Animals 11, 591 (doi:10.3390/ani11030591).

- Catarineu, C., Barberá, G.G., Reyes-López, J.L. 2018. Zoogeography of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of southeastern Iberian Peninsula. Sociobiology 65, 383-396 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v65i3.2822).

- Cerda, X., Arnan, X., Retana, J. 2013. Is competition a significant hallmark of ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) ecology? Myrmecological News 18: 131-147.

- Choe, J.C. 2010. Colony founding in social insects. Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior (Second Edition), pp. 310-316.

- Collingwood, C. A. 1979. The Formicidae (Hymenoptera) of Fennoscandia and Denmark. Fauna Entomol. Scand. 8: 1-174 (page 33, see also)

- Collingwood, C.A., Agosti, D., Sharaf, M.R., van Harten, A. 2011. Order Hymenoptera, family Formicidae. Arthropod fauna of the UAE 4: 405-474.

- Cordonnier, M., Blight, O., Angulo, E., Courchamp, F. 2020. Behavioral data and analyses of competitive interactions between invasive and native ant species. Animals 10, 2451 (doi:10.3390/ani10122451).

- Corin, S.E., Abbott, K.L., Ritchie, P.A., Lester, P.J. 2007. Large scale unicoloniality: the population and colony structure of the invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) in New Zealand. Insectes Sociaux 54: 275-282 (DOI 10.1007/s00040-007-0942-9).

- Corin, S.E., Lester, P.J., Abbott, K.L., Ritchie, P.A. 2007. Inferring historical introduction pathways with mitochondrial DNA: the case of introduced Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) into New Zealand. Diversity and Distributions 13, 510–518 (DOI 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00355.x).

- Crozier, R. H. 1969a [1968]. Cytotaxonomic studies on some Australian dolichoderine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Caryologia 21: 241-259 (page 250, karyotype described)

- Csata, E., Dussutour, A. 2019. Nutrient regulation in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): a review. Myrmecological News 29: 111-124 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_029:111).

- Culebra Mason, S., Catalano, P., Sgarbi, C., Verzero, F., Blondel, D. Ricci, M., Antonini, A. 2009. Utilización de trampas Pitfall con distintos atrayentes alimentarios para el monitoreo de hormigas en sistemas pastoriles. Boletin de Sanidad Vegetal Plagas 35: 187-192.

- Cushing, P.E. 2012. Spider-ant associations: An updated review of myrmecomorphy, myrmecophily, and myrmecophagy in spiders. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2012, 1–23 (doi:10.1155/2012/151989).

- Czechowski, W., Radchenko, A., Czechowska, W. 2002. The ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Poland. MIZ PAS Warsaw.

- Dahbi, A., Lenoir, A. 1998. Queen and colony odour in the multiple nest ant species, Cataglyphis iberica (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux 45, 301–313 (doi:10.1007/s000400050090).

- DaRocha, W. D., S. P. Ribeiro, F. S. Neves, G. W. Fernandes, M. Leponce, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2015. How does bromeliad distribution structure the arboreal ant assemblage (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on a single tree in a Brazilian Atlantic forest agroecosystem? Myrmecological News. 21:83-92.

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- De Biseau J.-C., L. Passera, D. Daloze, and S. Aron. 2004. Ovarian activity correlates with extreme changes in cuticular hydrocarbon profile in the highly polygynous ant, Linepithema humile. Journal of Insect Physiology 50: 585–593.

- Dekoninck, W., Ignace, D., Vankerkhoven, F., Wegnez, P. 2012. Verspreidingsatlas van de mieren van België. Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie 148: 95-186.

- Dekoninck, W., Wauters, N., Delsinne, T. 2019. Capitulo 35. Hormigas invasoras en Colombia. Hormigas de Colombia.

- Del Toro, I., Robbons, R.R., Pelini, S.L. 2012. The little things that run the world revisited: a review of ant-mediated ecosystem services and disservices (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 17: 133-146.

- Devenish, A.J.M., Newton, R.J., Bridle, J.R., Gomez, C., Midgley, J.J., Sumner, S. 2021. Contrasting responses of native ant communities to invasion by an ant invader, Linepithema humile. Biological Invasions 23, 2553–2571 (doi:10.1007/s10530-021-02522-7).

- Deyrup, M., Davis, L. & Cover, S. 2000. Exotic ants in Florida. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 126, 293-325.

- do Nascimento, L.E., Amaral, R.R., Ferreira, R.M.dos A., Trindade, D.V.S., do Nascimento, R.E., da Costa, T.S., Souto, R.N.P. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as potential mechanical vectors of pathogenic bacteria in a public hospital in the Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Journal of Medical Entomology 57: 1619–1626. (doi:10.1093/JME/TJAA062).

- Emery, C. 1888d. Über den sogenannten Kaumagen einiger Ameisen. Z. Wiss. Zool. 46: 378-412 (page 386, Combination in Iridomyrmex)

- Escarraga, M., Guerrero, R.J. 2016. The ant genus Linepithema (Formicidae Dolichoderinae) in Colombia. Zootaxa 4208: 446–458 (DOI 10.11646/zootaxa.4208.5.3).

- Espadaler, X. 2007. The ants of El Hierro (Canary Islands). Pages 113-127 in R. R. Snelling, B. L. Fisher, and P. S. Ward, editors. Advances in ant systematics (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): homage to E. O. Wilson - 50 years of contributions. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, Gainesville, FL. 80:690 pp.

- Fontenla, J.L., Brito, Y.M. 2011. Hormigas invasoras y vagabundas de Cuba. Fitosanidad 15(4), 253-259.

- Forel, A. 1908h. Ameisen aus Sao Paulo (Brasilien), Paraguay etc. gesammelt von Prof. Herm. v. Ihering, Dr. Lutz, Dr. Fiebrig, etc. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 58: 340-418 (page 395, male described)

- Fournier, D., Tindo, M., Kenne, M., Mbenoun Masse, P.S., Van Bossche, V., De Coninck, E., Aron, S. 2012. Genetic structure, nestmate recognition and behaviour of two cryptic species of the invasive Big-Headed Ant Pheidole megacephala. PLoS ONE 7(2): e31480 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031480).

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Gallardo, A. 1916b. Las hormigas de la República Argentina. Subfamilia Dolicoderinas. An. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. B. Aires 28: 1-130 (page 97, see also)

- Giannetti, D., Schifani, E., Castracani, C., Ghizzoni, M., Delaiti, M., Pfenner, F., Spotti, F.A., Mori, A., Ioriatti, C., Grasso, D.A. 2021. Assessing ant diversity in agroecosystems: the case of Italian vineyards of the Adige Valley. Redia 104, 97–109 (doi:10.19263/redia-104.21.11).

- Gochnour, B.M., Suiter, D.R., Booher, D. 2019. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) fauna of the Marine Port of Savannah, Garden City, Georgia (USA). Journal of Entomological Science 54, 417-429 (doi:10.18474/jes18-132).

- Godfrey, R.K., Oberski, J.T., Allmark, T., Givens, C., Hernandez-Rivera, J., Gronenberg, W. 2021. Olfactory system morphology suggests colony size drives trait evolution in Odorous Ants (Formicidae: Dolichoderinae). Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9, 733023 (doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.733023).

- Gonzalez, C., Wcislo, W., Cambra, R., Wheeler, T., Fernandez-Marın, H. 2016. A new ectoparasitoid species of Pseudogaurax Malloch, 1915 (Diptera: Chloropidae), attacking the fungus-growing ant, Apterostigma dentigerum Wheeler, 1925 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 109(4): 639–645 (doi:10.1093/aesa/saw023).

- Guillem, R., Bensusan, K. 2022. Thee new exotic species of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) for Madeira, with comments on its myrmecofauna. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 91: 321–333 (doi:10.3897/jhr.91.81624).

- Heller, N.E., Ingram, K.K., Gordon, D.M. 2008. Nest connectivity and colony structure in unicolonial Argentine ants. Insectes Sociaux 55: 397-403 (doi:10.1007/s00040-008-1019-0).

- Heterick, B.E. 2021. A guide to the ants of Western Australia. Part I: Systematics. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 86, 1-245 (doi:10.18195/issn.0313-122x.86.2021.001-245).

- Heterick, B.E. 2022. A guide to the ants of Western Australia. Part II: Distribution and biology. Records of the Western Australian Museum, supplement 86: 247-510 (doi:10.18195/issn.0313-122x.86.2022.247-510).

- Hill, J.G. 2015. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Big Thicket Region of Texas. Midsouth Entomologist 8: 24-34.

- Hisasue, Y., Tsuji, Y. 2020. Records of Nylanderia amia (Forel) in Shikoku, with notes of range expansion of Japan. ARI 41: 18-36.

- Hoey-Chamberlain, R., Rust, M.K. 2014. Food and bait preferences of Liometopum occidentale (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Entomological Science 49(1): 30-43.

- Hoey-Chamberlain, R., Rust, M.K., Klotz, J.H. 2013. A review of the biology, ecology and behavior of Velvety Tree Ants of North America. Sociobiology 60(1): 1-10.

- Hoey-Chamberlain, R.V. 2012. Food preference, survivorship, and intraspecific interactions of Velvety Tree Ants. M.S. thesis, University of California, Riverside.

- Hoffmann, B., Eldridge, J., Marston, C. 2023. The first eradication of an exotic ant species from the entirety of Australia: Pheidole fervens. Management of Biological Invasions, 14(4), 619–624 (doi:10.3391/mbi.2023.14.4.03).

- Horna-Lowell, E., Neumann, K.M., O’Fallon, S., Rubio, A., Pinter-Wollman, N. 2021. Personality of ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – underlying mechanisms and ecological consequences. Myrmecological News 31: 47-59 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:047).

- Hornfeldt, J.A., Ohyama, L., Lucky, A. 2020. Using behavioral experimentation to understand the social structure of the Little Fire Ant (Wasmannia auropunctata) in Florida. University of Florida Journal of Undergraduate Research 22: 1-9.

- Imai, H.T., Kihara, A., Kondoh, M., Kubota, M., Kuribayashi, S., Ogata, K., Onoyama, K., Taylor, R.W., Terayama, M., Yoshimura, M., Ugawa, Y. 2003. Ants of Japan. 224 pp, Gakken, Japan.

- Inoue, M. N., F. Ito, and K. Goka. 2015. Queen execution increases relatedness among workers of the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile. Ecology and Evolution. 5:4098-4107. doi:10.1002/ece3.1681

- Ipinza-Regla, J., A. M. Fernandez, M. A. Morales, and J. E. Araya. 2017. Hermetism between Camponotus morosus Smith and Linepithema humile Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Gayana. 81:22-27. doi:10.4067/S0717-65382017000100022

- Ipser, R.M., Brinkman, M.A., Gardner, W.A., Peeler, H.B. 2004. A survey of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia. Florida Entomologist 87: 253-260.

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87 (doi:10.3897@jhr.70.35207).

- Jacobs, S. 2020. Population genetic and behavioral aspects of male mating monopolies in Cardiocondyla venustula (Ph.D. thesis).

- Karaman, C., Kıran, K. 2018. New tramp ant species for Turkey: Tetramorium lanuginosum Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Trakya University Journal of Natural Sciences 19(1), e1-e4 (doi:10.23902/trkjnat.340008).

- Kiran, K., Karaman, C. 2020. Additions to the ant fauna of Turkey (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Zoosystema 42(18), 285-329 (doi:10.5252/zoosystema2020v42a18).

- Kirschenbaum, R. & Grace, J.K. 2008. Agonistic Responses of the Tramp Ants Anoplolepis gracilipes, Pheidole megacephala, Linepithema humile, and Wasmannia auropunctata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 51, 673-683.

- Krushelnycky, P., Suarez, A. 2009. Species profile Linepithema humile (Global Invasive Species Database).

- Lamelas-Lopez, L., Gabriel, R., Ros-Prieto, A., Borges, P. 2023. SLAM Project - Long Term Ecological Study of the Impacts of Climate Change in the natural forest of Azores: VI - Inventory of Arthropods of Azorean Urban Gardens. Biodiversity Data Journal 11, e98286 (doi:10.3897/bdj.11.e98286).

- Lapeva-Gjonova, A., Antonova, V. 2022. An updated checklist of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Bulgaria, after 130 years of research. Biodiversity Data Journal 10, e95599 (doi:10.3897/bdj.10.e95599).

- Lau, M.K., Ellison, A.M., Nguyen, A., Penick, C., DeMarco, B., Gotelli, N.J., Sanders, N.J., Dunn, R.R., Helms Cahan, S. 2019. Draft Aphaenogaster genomes expand our view of ant genome size variation across climate gradients. PeerJ 7, e6447 (doi:10.7717/PEERJ.6447).

- LeBrun, E.G., Plowes, R.M., Folgarait, P.J., Bollazzi, M., Gilbert, L.E. 2019. Ritualized aggressive behavior reveals distinct social structures in native and introduced range tawny crazy ants. PLOS ONE 14, e0225597 (doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0225597).

- Lee, C.-C., Weng, Y.-M., Lai, L.-C., Suarez, A.V., Wu, W.-J., Lin, C.-C., Yang, C.-C.S. 2020. Analysis of recent interception records reveals frequent transport of arboreal ants and potential predictors for ant invasion in Taiwan. Insects 11, 356 (doi:10.3390/INSECTS11060356).

- Lee, H.S., Kim, D.E., Lyu, D.P. 2020. Discovery of the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Mayr) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) in Korea. Korean Journal of Applied Entomology 59(1): 71-72 (doi:10.5656/KSAE.2020.02.0.012).

- Lester,P.J., Baring,C.W., Longson,C.G. & Hartley,S. 2003. Argentine and other ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in New Zealand horticultural ecosystems: distribution, hemipteran hosts, and review. New Zealand Entomologist 26: 79-89.

- Loiacono, M.S., Margarıa, C.B., Aquino, D.A. 2013. Diapriinae wasps (Hymenoptera: Diaprioidea: Diapriidae) associated with ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Argentina. Psyche 2013: Article 320590 (doi:10.1155/2013/320590).

- Lorite, P.; García, M. F.; Palomeque, T. 1998. Chromosome numbers in Spanish Formicidae. II. Subfamily Dolichoderinae. Sociobiology 32: 77-89 (page 77-89, karyoptype described)

- Lubertazzi, D. 2019. The ants of Hispaniola. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 162(2), 59-210 (doi:10.3099/mcz-43.1).

- Lutinski, J., de Filtro, M., Baucke, L., Dorneles, F., Lutinski, C., Guarda, C. 2021. Ant assemblages (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from areas under the direct influence of two small hydropower plants in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Environmental Sciences (Online), 1-9 (doi:10.5327/Z217694781030).

- Maák, I., Tóth, E., Lenda, M., Lőrinczi, G., Kiss, A., Juhász, O., Czechowski, W., Torma, A. 2020. Behaviours indicating cannibalistic necrophagy in ants are modulated by the perception of pathogen infection level. Scientific Reports 10, 17906 (doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74870-8).

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Markin, G.P., McCoy, C.W. 1968. The occurrence of a nematode, Diploscapter lycostoma, in the pharyngeal glands of the Argentine ant, Iridomyrmex humilis. Annals of the American Entomological Society of America 61, 505-509 (doi:10.1093/aesa/61.2.505).

- Mayr, G. 1868b. Formicidae novae Americanae collectae a Prof. P. de Strobel. Annu. Soc. Nat. Mat. Modena 3: 161-178 (page 164, worker described)

- Mayr, G. 1870b. Neue Formiciden. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 20: 939-996 (page 959, Combination in H. (Iridomyrmex))

- Molfini, M., Zapparoli, M., Genovesi, P., Carnevali, L., Audisio, P., Di Giulio, A., Bologna, M.A. 2020. A preliminary prioritized list of Italian alien terrestrial invertebrate species. Biological Invasions 22(8), 2385–2399 (doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02274-w).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Nakajima, T. 2018. Evaluation of ant diversity in urban areas and research on IPM. Japanese Journal of Environmental Zoology 29, 149–158.

- Obregon, R., M. R. Shaw, J. Fernandez-Haeger, and D. Jordano. 2015. Parasitoid and ant interactions of some Iberian butterflies (Insecta: Lepidoptera). Shilap-Revista De Lepidopterologia. 43:439-454.

- Oswalt, D.A. 2007. Nesting and foraging characteristics of the black carpenter ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus DeGeer (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ph.D. thesis, Clemson University.

- Oussalah, N., Marniche, F., Espadaler, X., Biche, M. 2019. Exotic ants from the Maghreb (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) with first report of the hairy alien ant Nylanderia jaegerskioeldi (Mayr) in Algeria. Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 45–58 (doi:10.32800/amz.2019.17.0045).

- Palomeque, T., O. Sanllorente, X. Maside, J. Vela, P. Mora, M. I. Torres, G. Periquet, and P. Lorite. 2015. Evolutionary history of the Azteca-like mariner transposons and their host ants. Science of Nature. 102. doi:10.1007/s00114-015-1294-3

- Park, J., Park, C.-H., Park, J. 2021. Complete mitochondrial genome of the H3 haplotype Argentine ant Linepithema humile (Mayr, 1868) (Formicidae; Hymenoptera). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 6, 786–788 (doi:10.1080/23802359.2021.1882900).

- Park, J., Xi, H., Park, J. 2019. The complete mitochondrial genome of Ochetellus glaber (Mayr, 1862) (Hymenoptera:Formicidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 147–149 (doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1698356).

- Park, S.-H., Hosoishi, S., Ogata, K. 2014. Long-term impacts of Argentine ant invasion of urban parks in Hiroshima, Japan. Journal of Ecology and Environment 37, 123–129 (doi:10.5141/ecoenv.2014.015).

- Pawluk, F., Borowiec, L., Salata, S. 2022. First record of Plagiolepis alluaudi Emery, 1894 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Poland. Annals of the Upper Silesian Museum in Bytom Entomology 31 (online 006) 1-5 (doi:10.5281/ZENODO.6522444).

- Pekar, S., L. Petrakova, O. Sedo, S. Korenko, and Z. Zdrahal. 2018. Trophic niche, capture efficiency and venom profiles of six sympatric ant-eating spider species (Araneae: Zodariidae). Molecular Ecology. 27:1053-1064. doi:10.1111/mec.14485

- Pérez‐Marcos, M., López‐Gallego, E., Arnaldos, M.I., Martínez‐Ibáñez, D., García, M.D. 2020. Formicidae (Hymenoptera) community in corpses at different altitudes in a semiarid wild environment in the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula. Entomological Science 23, 297–310 (doi:10.1111/ENS.12422).

- Piqueret, B., Montaudon, É., Devienne, P., Leroy, C., Marangoni, E., Sandoz, J.-C., d’Ettorre, P. 2023. Ants act as olfactory bio-detectors of tumours in patient-derived xenograft mice. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 290: 20221962 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.1962).

- Psalti, M.N., Gohlke, D., Libbrecht, R. 2021. Experimental increase of worker diversity benefits brood production in ants. BMC Ecology and Evolution 21, 163 (doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01890-x).

- Qiu, B., Larsen, R.S., Chang, N.-C., Wang, J., Boomsma, J.J., Zhang, G. 2018. Towards reconstructing the ancestral brain gene-network regulating caste differentiation in ants. Nature Ecology, Evolution 2, 1782–1791. (doi:10.1038/S41559-018-0689-X).

- Rosas-Mejía, M., Guénard, B., Aguilar-Méndez, M. J., Ghilardi, A., Vásquez-Bolaños, M., Economo, E. P., Janda, M. 2021. Alien ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Mexico: the first database of records. Biological Invasions 23(6), 1669–1680 (doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02423-1).

- Roux, J., Privman, E., Moretti, S., Daub, J.T., Robinson-Rechavi, M., Keller, L. 2014. Patterns of positive selection in seven ant genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31, 1661–1685 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msu141).

- Saito-Morooka, F., Fukuhara, K., Suda, K. 2015. The ant fauna of Rissho University at Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture (Insecta, Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Bulletin of geo-environmental science (17), 35-39.

- Salata, S., Borowiec, L., Trichas, A. 2020. Review of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Crete, with keys to species determination and zoogeographical remarks. Monographs of the Upper Silesian Museum No 12: 5–296 (doi:10.5281/ZENODO.3738001).

- Schär, S., Menchetti, M., Schifani, E., Hinojosa, J.C., Platania, L., Dapporto, L., Vila, R. 2020. Integrative biodiversity inventory of ants from a Sicilian archipelago reveals high diversity on young volcanic islands (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Organisms Diversity, Evolution 20, 405–416 (doi:10.1007/s13127-020-00442-3).

- Schifani, E. (2022). The new checklist of the Italian fauna: Formicidae. Biogeographia – The Journal of Integrative Biogeography 37, ucl006 (doi:10.21426/b637155803).

- Schifani, E., Nalini, E., Gentile, V., Alamanni, F., Ancona, C., Caria, M., Cillo, D., Bazzato, E. 2021. Ants of Sardinia: An updated checklist based on new faunistic, morphological and biogeographical notes. Redia 104, 21–35 (doi:10.19263/redia-104.21.03).

- Schultner, E., Pulliainen, U. 2020. Brood recognition and discrimination in ants. Insectes Sociaux 67, 11–34 (doi:10.1007/s00040-019-00747-3).

- Seifert, B. 2022. The ant genus Cardiocondyla (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): The species groups with Oriental and Australasian origin. Diversity 15, 25 (doi:10.3390/d15010025).

- Sharaf, M.R., Abdel-Dayem, M.S., Mohamed, A.A., Fisher, B.L., Aldawood, A.S. 2020. A preliminary synopsis of the ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Qatar with remarks on the zoogeography. Annales Zoologici 70: 533-560 (doi:10.3161/00034541anz2020.70.4.005).

- Shattuck, S. O. 1992a. Review of the dolichoderine ant genus Iridomyrmex Mayr with descriptions of three new genera (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Aust. Entomol. Soc. 31: 13-18 (page 16, Combination in Linepithema)

- Shattuck, S. O. 1994. Taxonomic catalog of the ant subfamilies Aneuretinae and Dolichoderinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Univ. Calif. Publ. Entomol. 112:i-xix, 1-241. (page 123, see also)

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Siddiqui, J.A., Bamisile, B.S., Khan, M.M., Islam, W., Hafeez, M., Bodlah, I., Xu, Y. 2021. Impact of invasive ant species on native fauna across similar habitats under global environmental changes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28(39), 54362–54382 (doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15961-5).

- Silva, P.S., Koch, E.B. de A., Arnhold, A., Delabie, J.H.C. 2022. Review of distribution modeling in ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) biogeographic studies. Sociobiology 69(4), e7775 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v69i4.7775).

- Smith, C. D. et al. (2011) Draft genome of the globally widespread and invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). PNAS. 108(14):5673-5678. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008617108

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. i-xvi, 1199-2209. (page 1418, see also)

- Stukalyuk, S., Radchenko, A., Akhmedov, A., Reshetov, A., Netsvetov, M. 2021. Acquisition of invasive traits in ant, Crematogaster subdentata Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in urban environments. Serangga 26: 1-29.

- Sunamura, E., Tamura, S., Urano, T., Shoda-Kagaya, E. 2020. Predation of invasive red-necked longhorn beetle Aromia bungii (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) eggs and hatchlings by native ants in Japan. Applied Entomology and Zoology 55, 291–298 (doi:10.1007/S13355-020-00681-Y).

- Takahashi, N., Touyama, Y., Kameyama, T., Ito, F. 2018. Effect of the Argentine ant on the specialist myrmecophilous cricket Myrmecophilus kubotai in western Japan. Entomological Science 21, 343–346 (doi:10.1111/ENS.12314).

- Terayama, M., Sunamura, E., Fujimaki, R., Ono, T., Eguchi, K. 2021. A Surprisingly Non-attractiveness of Commercial Poison Baits to Newly Established Population of White-Footed Ant, Technomyrmex brunneus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in a Remote Island of Japan. Sociobiology 68, 5898 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v68i1.5898).

- Tibcherani, M., Aranda, R., Mello, R.L. 2020. Time to go home: The temporal threshold in the regeneration of the ant community in the Brazilian savanna. Applied Soil Ecology 150, 103451 (doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.103451).

- Trigos-Peral, G., Abril, S., Angulo, E. 2020. Behavioral responses to numerical differences when two invasive ants meet: the case of Lasius neglectus and Linepithema humile. Biological Invasions (doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02412-4).

- Tseng, S.-P. 2020. Evolutionary history of a global invasive ant, Paratrechina longicornis (Dissertation_全文 ). Ph.D. thesis, Kyoto University.

- Ulysséa, M.A., Brandão, C.R.F. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57, 217–224 (doi:10.1590/s0085-56262013005000002).

- Ward, P. S. 1987. Distribution of the introduced Argentine ant (Iridomyrmex humilis) in natural habitats of the lower Sacramento Valley and its effects on the indigenous ant fauna. Hilgardia 55(2 2: 1-16 (page 1, see also)

- Wetterer, J.K. 2017. Invasive ants of Bermuda revisited. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 54, 33–41 (doi:10.3897/jhr.54.11444).

- Wetterer, J.K., Espadaler, X., Ashmole, N.P., Mendel, H., Cutler, C., Endeman, J. 2007. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the South Atlantic islands of Ascension Island, St Helena, and Tristan da Cunha. Myrmecological News 10: 29-37.

- Wetterer, J.K., Wetterer, A.L. 2004. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Bermuda. Florida Entomologist 87(2), 212–221 (doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2004)087[0212:ahfob2.0.CO;2]).

- Wetterer, J.K., Wild, A.L. et al. 2009. Worldwide spread of the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 12: 187-194.

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1951. The ant larvae of the subfamily Dolichoderinae. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 53: 169-210 (page 186, larva described)

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1990a [1989]. Notes on ant larvae. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 115: 457-473 (page 465, see also)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1913c. [Untitled. Description of Iridomyrmex humilis Mayr.]. Pp. 27-29 in: Newell, W., Barber, T. C. The Argentine ant. U. S. Dep. Agric. Bur. Entomol. Bull. 122:1-98. (page 28, queen described)

- Wiernasz, D.C., Hines, J., Parker, D.G., Cole, B.J. 2008. Mating for variety increases foraging activity in the harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Molecular Ecology 17, 1137–1144 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03646.x).

- Wild, A. L. 2007a. Taxonomic revision of the ant genus Linepithema (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). University of California Publications in Entomology. 126:1-159.

- Wild, A.L. 2004. Taxonomy and distribution of the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 97, 1204-1215.

- Witt, A.B.R., Giliomee, J.H. 2005. Dispersal of elaiosome-bearing seeds of six plant species by native species of ants and the introduced invasive ant, Linepithema humile (Mayr) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. African Plant Protection 11, 1-7.

- Xiong, Z., He, D., Guang, X., Li, Q. 2023. Novel tRNA gene rearrangements in the mitochondrial genomes of poneroid ants and phylogenetic implication of Paraponerinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Life 1310, 2068 (doi:10.3390/life13102068).

- Yu, Y. 2016. Risk of alien species introduction to Ogasawara Islands : Case study of ants at Tokyo Port. World Heritage Studies 1, 86-89.

Additional References

See also a list of some recent studies of the Argentine ant.

- Zhou, X., Slone, J.D., Rokas, A., Berger, S.L., Liebig, J., Ray, A., Reinberg, D., Zwiebel, L.J. 2012. Phylogenetic and transcriptomic analysis of chemosensory receptors in a pair of divergent ant species reveals sex-specific signatures of odor coding. PLoS Genetics 8, e1002930 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002930).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Andrade T., G. D. V. Marques, K. Del-Claro. 2007. Diversity of ground dwelling ants in Cerrado: an analysis of temporal variations and distinctive physiognomies of vegetation (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 50(1): 121-134.

- Borgmeier T. 1923. Catalogo systematico e synonymico das formigas do Brasil. 1 parte. Subfam. Dorylinae, Cerapachyinae, Ponerinae, Dolichoderinae. Archivos do Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro) 24: 33-103.

- Caldart V. M., S. Iop, J. A. Lutinski, and F. R. Mello Garcia. 2012. Ants diversity (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of the urban perimeter of Chapecó county, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoociências 14 (1, 2, 3): 81-94.

- Clemes Cardoso D., and J. H. Schoereder. 2014. Biotic and abiotic factors shaping ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) assemblages in Brazilian coastal sand dunes: the case of restinga in Santa Catarina. Florida Entomologist 97(4): 1443-1450.

- Clemes Cardoso D., and M. Passos Cristiano. 2010. Myrmecofauna of the Southern Catarinense Restinga sandy coastal plain: new records of species occurrence for the state of Santa Catarina and Brazil. Sociobiology 55(1b): 229-239.

- Corassa J. N., I. C. Magistrali, J. C. Moreno, E. B. Cantarelli, and A. Corassa. Effect of formicid granulated baits on non-target ants biodiversity in eucalyptus plantations litter. Comunicata Scientiae 4(1): 35-42.

- Costa-Milanez C. B., G. Lourenco-Silva, P. T. A. Castro, J. D. Majer, and S. P. Ribeiro. 2014. Are ant assemblages of Brazilian veredas characterised by location or habitat type? Braz. J. Biol. 74(1): 89-99.

- Dias N. S., R. Zanetti, M. S. Santos, J. Louzada, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2008. Interaction between forest fragments and adjacent coffee and pasture agroecosystems: responses of the ant communities (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Iheringia, Sér. Zool., Porto Alegre, 98(1): 136-142.

- Fagundes R., G. Terra, S. P. Ribeiro, and J. D. Majer. 2010. The Bamboo Merostachys fischeriana (Bambusoideae: Bambuseae) as a Canopy Habitat for Ants of Neotropical Montane Forest. Neotropical Entomology 39(6):906-911

- Favretto M. A., E. Bortolon dos Santos, and C. J. Geuster. 2013. Entomofauna from West of Santa Catarina State, South of Brazil. EntomoBrasilis 6 (1): 42-63.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Fleck M. D., E. Bisognin Cantarelli, and F. Granzotto. 2015. Register of new species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Rio Grande do Sul state. Ciencia Florestal, Santa Maria 25(2): 491-499.

- Forel A. 1908. Ameisen aus Sao Paulo (Brasilien), Paraguay etc. gesammelt von Prof. Herm. v. Ihering, Dr. Lutz, Dr. Fiebrig, etc. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 58: 340-418.

- Gallardo A. 1916. Las hormigas de la República Argentina. Subfamilia Dolicoderinas. Anales del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Buenos Aires 28: 1-130.

- Gallardo A. 1920. Las hormigas de la República Argentina. Subfamilia Dorilinas. Anales del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Buenos Aires 30: 281-410.

- Heller, N.E. 2004. Colony structure in introduced and native populations of the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile. Insectes Sociaux 51(4): 378-386.

- Ilha C., J. A. Lutinski, D. Von Muller Pereira, F. R. Mello Garcia. 2009. Riqueza de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Bacia da Sanga Caramuru, municipio de Chapeco-SC. Biotemas 22(4): 95-105.

- Iop S., V. M. Caldart, J. A. Lutinski, and F. R. Mello Garcia. 2009. Formigas urbanas da cidade de Xanxerê, Santa Catarina, Brasil. Biotemas 22(2): 55-64.

- Kamura, C.M., M.S.C. Morini, C.J. Figueiredo, O.C. Bueno, and A.E.C. Campos-Farinha. 2007. Comunidades de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) em um ecossistema urbano próximo à Mata Atlântica. Brazilian Journal of Biology 67(4): 635-641

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kusnezov N. 1953. La fauna mirmecológica de Bolivia. Folia Universitaria. Cochabamba 6: 211-229.

- Lapola D. M., and H. G. Fowler. 2008. Questioning the implementation of habitat corridors: a case study in interior São Paulo using ants as bioindicators. Braz. J. Biol., 68(1): 11-20.

- LeBrun, E.G., C. V. Tillberg, A. V. Suarez, P. J. Folgarait, C. R. Smith and D. A. Holway. 2007. An Experimental Study of Competition between Fire Ants and Argentine Ants in Their Native Range. Ecology 88(1):63-75

- Luederwaldt H. 1918. Notas myrmecologicas. Rev. Mus. Paul. 10: 29-64.

- Lutinski J. A., B. C. Lopes, and A. B. B.de Morais. 2013. Diversidade de formigas urbanas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de dez cidades do sul do Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 13(3): 332-342.

- Lutinski J. A., F. R. Mello Garcia, C. J. Lutinska, and S. Iop. 2008. Ants diversity in Floresta Nacional de Chapecó in Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Ciência Rural, Santa Maria 38(7): 1810-1816.

- Marinho C. G. S., R. Zanetti, J. H. C. Delabie, M. N. Schlindwein, and L. de S. Ramos. 2002. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Diversity in Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae) Plantations and Cerrado Litter in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 31(2): 187-195.

- Marques G. D. V., and K. Del-Claro. 2006. The Ant Fauna in a Cerrado area: The Influence of Vegetation Structure and Seasonality (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 47(1): 1-18.

- Martinez M.J. and Weis E.M. 2011. field observations of two species of invasive ants, Linepithema humile Mayr, 1868 and Tetramoirum bicarinatum Nylander, 1846 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), at a suburban park in Southern California. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 87: 57-61

- Menozzi C. 1926. Neue Ameisen aus Brasilien. Zoologischer Anzeiger. 69: 68-72.

- Morini M. S. de C., C. de B. Munhae, R. Leung, D. F. Candiani, and J. C. Voltolini. 2007. Comunidades de formigas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) em fragmentos de Mata Atlântica situados em áreas urbanizadas. Iheringia, Sér. Zool., Porto Alegre, 97(3): 246-252.

- Oliveira R. F., L. C. de Almeida, D. R. de Suza, C. Bortoli Munhae, O. C. Bueno, and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2012. Ant diversity (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and predation by ants on the different stages of the sugarcane borer life cycle Diatraea saccharalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 109: 381387.

- Orr M. R., and S. H. Seike. 1998. Parasitoids deter foraging by Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) in their native habitat in Brazil. Oecologia 117: 420-425.

- Pacheco R., and H. L. Vasconcelos. 2007. Invertebrate conservation in urban areas: ants in the Brazilian Cerrado. Landscape and Urban Planning 81: 193199.

- Pacheco, R., R.R. Silva, M.S. de C. Morini, C.R.F. Brandao. 2009. A Comparison of the Leaf-Litter Ant Fauna in a Secondary Atlantic Forest with an Adjacent Pine Plantation in Southeastern Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 38(1):055-065

- Pedersen, J.S., M.J.B. Krieger, V. Vogel, T. Giraud and L. Keller 2006. Native Supercolonies of Unrelated Individuals in the Invasive Argentine Ant. Evolution 60(4):782-791

- Pereira M. C., J. H. C. Delabie, Y. R. Suarez, and W. F. Antonialli Junior. 2013. Spatial connectivity of aquatic macrophytes and flood cycle influence species richness of an ant community of a Brazilian floodplain. Sociobiology 60(1): 41-49.

- Pignalberi C. T. 1961. Contribución al conocimiento de los formícidos de la provincia de Santa Fé. Pp. 165-173 in: Comisión Investigación Científica; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Argentina) 1961. Actas y trabajos del primer Congreso Sudamericano de Zoología (La Plata, 12-24 octubre 1959). Tomo III. Buenos Aires: Librart, 276 pp.

- Piva A., and A. E. de C. Campos. 2012. Ant Community Structure (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Two Neighborhoods with Different Urban Profiles in the City of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Psyche 2012 (390748): 1-8

- Ramos L. S., R. Z. B. Filho, J. H. C. Delabie, S. Lacau, M. F. S. dos Santos, I. C. do Nascimento, and C. G. S. Marinho. 2003. Ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the leaf-litter in cerrado stricto sensu areas in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Lundiana 4(2): 95-102.

- Ramos L. de S., C. G. S. Marinho, R. Zanetti, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2003. Impacto de iscas formicidas granuladas sobre a mirmecofauna não-alvo em eucaliptais segundo duas formas de aplicacação / Impact of formicid granulated baits on non-target ants in eucalyptus plantations according to two forms of application. Neotropical Entomology 32(2): 231-237.

- Ramos L. de S., R. Zanetti, C. G. S. Marinho, J. H. C. Delabie, M. N. Schlindwein, and R. P. Almado. 2004. Impact of mechanical and chemical weedings of Eucalyptus grandis undergrowth on an ant community (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Árvore 28(1): 139-146.

- Ribas C. R., J. H. Schoereder, M. Pic, and S. M. Soares. 2003. Tree heterogeneity, resource availability, and larger scale processes regulating arboreal ant species richness. Austral Ecology 28(3): 305-314.

- Rosa da Silva R. 1999. Formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do oeste de Santa Catarina: historico das coletas e lista atualizada das especies do Estado de Santa Catarina. Biotemas 12(2): 75-100.

- Santoandre S., J. Filloy, G. A. Zurita, and M. I. Bellocq. 2019. Ant taxonomic and functional diversity show differential response to plantation age in two contrasting biomes. Forest Ecology and Management 437: 304-313.

- Santos M. S., J. N. C. Louzada, N. Dias, R. Zanetti, J. H. C. Delabie, and I. C. Nascimento. 2006. Litter ants richness (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in remnants of a semi-deciduous forest in the Atlantic rain forest, Alto do Rio Grande region, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Iheringia, Sér. Zool., Porto Alegre, 96(1): 95-101.

- Santschi F. 1912. Quelques fourmis de l'Amérique australe. Revue Suisse de Zoologie 20: 519-534.

- Santschi F. 1916. Formicides sudaméricains nouveaux ou peu connus. Physis (Buenos Aires). 2: 365-399.

- Santschi F. 1925. Fourmis des provinces argentines de Santa Fe, Catamarca, Santa Cruz, Córdoba et Los Andes. Comunicaciones del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural "Bernardino Rivadavia" 2: 149-168.

- Schoereder J. H., T. G. Sobrinho, M. S. Madureira, C. R. Ribas, and P. S. Oliveira. 2010. The arboreal ant community visiting extrafloral nectaries in the Neotropical cerrado savanna. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 3: 3-27.

- Silva F. H. O., J. H. C. Delabie, G. B. dos Santos, E. Meurer, and M. I. Marques. 2013. Mini-Winkler Extractor and Pitfall Trap as Complementary Methods to Sample Formicidae. Neotrop Entomol 42: 351358.

- Silvestre R., M. F. Demetrio, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2012. Community Structure of Leaf-Litter Ants in a Neotropical Dry Forest: A Biogeographic Approach to Explain Betadiversity. Psyche doi:10.1155/2012/306925

- Tillberg, C.V., D.P. McCarthy, A.G. Dolezal and A.V. Suarez. 2006. Measuring the trophic ecology of ants using stable isotopes. Insectes Sociaux 53:65-69

- Ulyssea M.A., C. E. Cereto, F. B. Rosumek, R. R. Silva, and B. C. Lopes. 2011. Updated list of ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) recorded in Santa Catarina State, southern Brazil, with a discussion of research advances and priorities. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(4): 603-611.

- Vasconcelos, H.L., J.M.S. Vilhena, W.E. Magnusson and A.L.K.M. Albernaz. 2006. Long-term effects of forest fragmentation on Amazonian ant communities. Journal of Biogeography 33:1348-1356

- Vittar, F. 2008. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Mesopotamia Argentina. INSUGEO Miscelania 17(2):447-466

- Vittar, F., and F. Cuezzo. "Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina." Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina (versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471) 67, no. 1-2 (2008).

- Wild A. L. 2004. Taxonomy and distribution of the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 97: 1204-1215

- Wild A. L. 2007. Taxonomic revision of the ant genus Linepithema (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). University of California Publications in Entomology 126: 1-151

- Wild, A. L.. "A catalogue of the ants of Paraguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Zootaxa 1622 (2007): 1-55.

- Zoppas de Albuquerque E., and E. Diehl. 2009. Análise faunística das formigas epígeas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) em campo nativo no Planalto das Araucárias, Rio Grande do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 53(3): 398403.

- da Silva Araujo, M., Castro Della Lucia, T.M., DA VEIGA, Clayton E y CARDOSO DO NASCIMENTO, Ivan. 2004. Efeito da queima da palhada de cana-de-açúcar sobre comunidade de formicídeos. Ecol. austral. 14(2): 191-200.

- da Silva T. F., D. Russ Solis, T. de Carvalho Moretti, A. Calazans da Silva, M. E. Din Mostafa Habib. 2009. House-infesting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a municipality of southeastern Brazil. Sociobiology 54(1): 153-159.

- de Almeida Soares S., Y. R. Suarez, W. D. Fernandes, P. M. Soares Tenorio, J. H. C. Delabie, and W. F. Antonialli-Junior. 2013. Temporal variation in the composition of ant assemblages (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) on trees in the Pantanal floodplain, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Rev. Bras. entomol. 57: 84-90

- de Zolessi, L.C., Y.P. de Abenante and M.E. Philippi. 1987. Lista sistemática de las especies de formícidos del Uruguay. Comunicaciones Zoologicas del Museo de Historia Natural de Montevideo 11(165):1-9

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- Highly invasive

- Supercolonies

- Polygynous

- Photo Gallery

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- South subtropical

- South temperate

- FlightMonth

- Phorid fly Associate

- Host of Apocephalus silvestrii

- Host of Ceratoconus setipennis

- Host of Pseudacteon pusillus

- Syrphid fly Associate

- Host of Mixogaster lanei

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis coreopsidis

- Host of Aphis gossypii

- Host of Aphis nerii

- Host of Aphis spiraecola

- Host of Chaitophorus populicola

- Host of Myzus persicae

- Diapriid wasp Associate

- Host of Basalys sp.

- Host of Trichopria sp.

- Aphelinid wasp Associate

- Host of Aphytis melinus

- Host of Cales noacki

- Host of Eretmocerus sp.

- Encyrtid wasp Associate

- Host of Comperiella bifasciata

- Host of Leptomastix dactylopii

- Host of Metaphycus anneckei

- Host of Metaphycus hageni

- Host of Metaphycus lounsburyi

- Host of Ananusia longiscapus

- Butterfly Associate

- Host of Lampides boeticus

- Spider Associate

- Host of Zodarion sp.

- Nematode Associate

- Host of Diploscapter lycostoma

- Virus Associate

- Host of Aparavirus: Kashmir bee virus

- Host of Iflavirus: Deformed wing virus

- Host of Linepithema humile virus-1

- Host of Triatovirus: Black queen cell virus

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Dolichoderinae

- Leptomyrmecini

- Linepithema

- Linepithema humile

- Dolichoderinae species

- Leptomyrmecini species

- Linepithema species

- Ssr