Cyphomyrmex rimosus

| Cyphomyrmex rimosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Cyphomyrmex |

| Species: | C. rimosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyphomyrmex rimosus (Spinola, 1851) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

A tropical species, or complex of closely related species, that has been introduced to other areas from its native range in Central and South America.

| At a Glance | • Invasive |

Identification

Using published keys (Kempf 1966, Snelling and Longino 1992) some collections from some areas readily agree with published ideas of what constitutes the present set of valid species in this complex. In other cases individuals or nests series are difficult to determine to species, which in turn suggests our current understanding of the rimosus-species group needs a thorough taxonomic reevaluation. See the nomenclature section below for additional information.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

A common, introduced species found throughout Florida. It occurs in both undisturbed mesic or wet woods and various disturbed habitats. This species has only recently become abundant in northern Florida (where there are no early records) and is now sympatric with Cyphomyrmex minutus in southern Florida (Deyrup 1991). Pest status: none. First published Florida records: Deyrup and Trager 1986 (as C. fuscus Emery), Johnson 1986; earlier specimens: 1957. (Deyrup, Davis & Cover, 2000.)

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 25.86055° to -64.36°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States.

Neotropical Region: Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil (type locality), Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, French Guiana, Galapagos Islands, Greater Antilles, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Lesser Antilles, Mexico, Netherlands Antilles, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

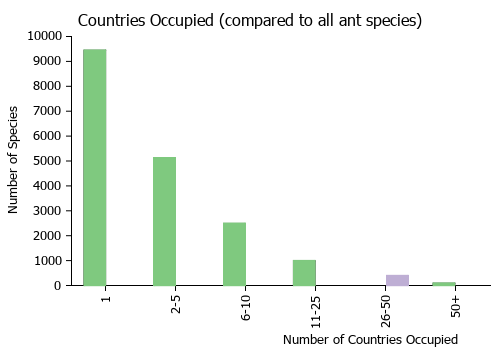

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

|

This species depends on fungi that it grows on compost beds of vegetable matter mixed with scavenged bits of dead insects; it does not cut pieces of leaves from living plants.

Stuble et al. (2010) found that this species removes seeds while Atchison & Lucky (2022) did not observe this behaviour.

Regional Notes

Brazil

Ramos-Lacau et al. (2015) found this species co-occurring with Mycetophylax lectus and Mycetophylax strigatus in savanna-forest in Southeast Brazil. Colonies were found nesting in the ground. Each nest had a single, simple circular nest-entrance. These averaged a few mm in diameter and did not have any well formed nest mound.

Costa Rica

Longino (2004) reports the following: This species, possibly a complex of cryptic species (see comments), occurs in a wide range of habitats, including dry open ground of synanthropic habitats, seasonal dry forest, and lowland rainforest. This is the most abundant species in open areas, replaced in abundance by Cyphomyrmex salvini in wet forest habitats. Nests are in the soil, under stones, or under dead wood on the ground. I have also found nests in subarboreal cavities, such as rotten knots in tree trunks and dead wood suspended in vegetation, but usually within 2m of the ground. Colonies can be polygynous; one nest I observed contained at least four dealate queens. Workers forage on the surface, harvesting small insect parts and caterpillar droppings for use as substrate for fungal gardens. In Corcovado National Park I observed workers regularly visiting extrafloral nectaries of Passiflora pittieri.

Florida

Snelling and Longino (1992) - The following biological information has been provided by J.C. Trager for two samples collected 16 June, 1984 in Gainesville:

These ... were under boards in a weedy lot next to my lab. The brood and fungus gardens of the colonies were kept apart but adjacent on grass stolons or compacted grass blades near the center of single nearly round 5-8 cm-diam. chambers, 1-2 cm deep. Males were clustered on the underside of the board (the warmest, driest part of the nest). The insect fragments, grasshopper feces, etc. collected with one series were heaped separately at opposite sides of the periphery of the nest chamber. This rigid compartmentalization of castes and materials is typical of... this ant. [Queens are usually] associated with the brood [and] most often there are 1 or 2 queens per nest, but I've seen 3 or 4 on occasion. Mating flights take place at the first faint light of dawn, following heavy rains alter a dry spell during the summer months.

Deyrup, Davis & Cover (2000): This species appears to have entered the state from the north or northwest, where it is most common, but it now occurs throughout the state. It is found in a great variety of natural and modified habitats. This is a fungus-growing species that is unlikely to compete with other arthropods, with the exception of Trachymyrmex septentrionalis in sandy uplands and the supposedly native Cyphomyrmex minutus in south Florida. It is possible that some scavenging arthropods will be affected by high populations of C. rimosus, but in general this species will probably have minimal impact on native species.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria spp. (a parasite) in Panama (Fernández-Marín et al., 2006) (at least 4 species of Acanthopria involved).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Mimopriella sp. (a parasite) in Panama (Fernández-Marín et al., 2006).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 1 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 2 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 3 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Acanthopria sp. 4 (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the diapriid wasp Mimopriella sp. (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode independent; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

Worker ants grasped at, bit, and in some cases, killed adult wasps that emerged in artificial nests or tried to enter natural nests (Fernández-Marín et al., 2006).

Flight Period

| X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Life History Traits

- Mean colony size: 100 (Blum et al., 1964; Beckers et al., 1989)

- Foraging behaviour: solitary forager (Blum et al., 1964; Beckers et al., 1989)

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103839. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0173243. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CDRS, Galapagos, Ecuador. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0179472. Photographer Erin Prado, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0103846. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0173242. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CDRS, Galapagos, Ecuador. |

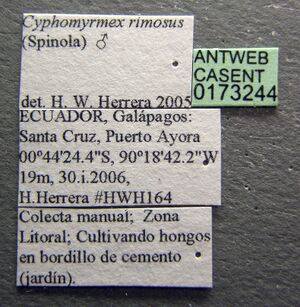

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0103840. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0173244. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CDRS, Galapagos, Ecuador. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- rimosus. Cryptocerus rimosus Spinola, 1851b: 49 (w.m.) BRAZIL (Pará).

- Type-material: lectotype worker (by designation of Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491), 3 paralectotype males.

- Type-locality: lectotype Brazil: Pará, Belém, 1846 (V. Ghiliani); paralectotypes with same data.

- Type-depository: MRSN.

- [Also described as new by Spinola, 1853: 65.]

- Emery, 1894c: 224 (q.); Wheeler, G.C. 1949: 668 (l.).

- Combination in Cyphomyrmex: Emery, 1893h: 2;

- combination in Atta (Cyphomyrmex): Forel, 1912e: 188;

- combination in Cyphomyrmex: Bruch, 1914: 217.

- Status as species: Smith, F. 1853: 223; Smith, F. 1858b: 190; Smith, F. 1862d: 409; Mayr, 1863: 406; Roger, 1863b: 38; Dalla Torre, 1893: 150; Forel, 1893g: 374; Emery, 1893h: 2; Emery, 1894c: 225; Forel, 1895b: 137; Forel, 1897b: 300; Forel, 1899c: 40; Wheeler, W.M. 1905b: 130; Wheeler, W.M. 1907a: 275; Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 719 (redescription); Forel, 1908e: 69; Wheeler, W.M. 1911b: 170; Forel, 1911e: 257; Bruch, 1914: 217; Wheeler, W.M. & Mann, 1914: 42; Gallardo, 1916d: 323; Mann, 1916: 459; Luederwaldt, 1918: 39; Wheeler, W.M. 1922c: 13; Emery, 1924d: 342; Wheeler, W.M. 1925a: 45; Borgmeier, 1927c: 126; Aguayo, 1932: 223; Borgmeier, 1934: 107; Weber, 1938b: 188; Weber, 1940a: 410 (in key); Weber, 1941b: 99; Weber, 1945: 5; Weber, 1946b: 116; Weber, 1948b: 83; Kusnezov, 1949d: 439; Creighton, 1950a: 316; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 829; Kusnezov, 1953b: 338; Kusnezov, 1957b: 10 (in key); Smith, M.R. 1958c: 137; Weber, 1958d: 259; Kempf, 1961b: 519; Kempf, 1966: 198; Smith, M.R. 1967: 363; Kempf, 1972a: 93; Hunt & Snelling, 1975: 22; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1410; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 147; Zolessi, et al. 1988: 5; Deyrup, et al. 1989: 98; Brandão, 1991: 339; Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168; Deyrup, et al. 2000: 300; Mackay & Mackay, 2002: 102; Deyrup, 2003: 44; MacGown & Forster, 2005: 69; Wild, 2007b: 33; Branstetter & Sáenz, 2012: 258; Bezděčková, et al. 2015: 117; Deyrup, 2017: 70; Fernández & Serna, 2019: 850; Lubertazzi, 2019: 109; Herrera, Tocora, et al. 2024: 178.

- Senior synonym of cochunae: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Senior synonym of curiapensis: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Senior synonym of difformis: Emery, 1893h: 2; Forel, 1893e: 607; Forel, 1893g: 374; Dalla Torre, 1893: 150; Emery, 1894c: 224; Forel, 1895b: 137; Forel, 1899c: 40; Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 719; Gallardo, 1916d: 323; Emery, 1924d: 342; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 829; Kempf, 1966: 162; Kempf, 1972a: 93; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1410; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 147; Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Senior synonym of fuscula: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Senior synonym of fuscus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- Distribution: Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Brazil, French Guiana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Réunion I. (introduction), Suriname, Trinidad (+ Tobago), Uruguay, U.S.A., Venezuela.

- cochunae. Cyphomyrmex rimosus subsp. cochunae Kusnezov, 1949d: 439 (w.) ARGENTINA (Tucumán).

- Type-material: 216 syntype workers.

- Type-localities: ca 170 workers Argentina: Rio Cochuna, Concepción road at Andalgalá, 6.v.1948, nos 1855, 1875 (N. Kusnezov), 1 worker Argentina: Tucumán, La Reducción, ca 22 km. S Tucumán, Calimayo lake, no. 1517 (N. Kusnezov), 45 workers Tucumán, Quebrada de la Sosa, nos 3468, 3476 (N. Kusnezov).

- Type-depository: IMLT.

- Status as species: Kusnezov, 1957b: 10 (in key).

- Subspecies of rimosus: Kusnezov, 1953b: 338; Kempf, 1966: 162; Kempf, 1972a: 93.

- Junior synonym of rimosus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 167.

- curiapensis. Cyphomyrmex rimosus subsp. curiapensis Weber, 1938b: 190 (w.q.m.) VENEZUELA.

- Type-material: syntype workers, syntype queens, syntype males (numbers not stated, “one colony”).

- Type-locality: Venzuela: Orinoco Delta, Curiapo I., 7.ii.1935 (N.A. Weber).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Subspecies of rimosus: Weber, 1940a: 411 (in key); Weber, 1946b: 119.

- Junior synonym of fuscus: Weber, 1958d: 260; Kempf, 1966: 162; Kempf, 1972a: 94.

- Junior synonym of rimosus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- difformis. Meranoplus difformis Smith, F. 1858b: 195 (w.) BRAZIL (Pará).

- Type-material: holotype (?) worker.

- [Note: no indication of number of specimens is given.]

- Type-locality: Brazil: Santarem (no collector’s name).

- Type-depository: BMNH.

- [Misspelled as deformis by Roger, 1863a: 210, and many others.]

- Roger, 1863a: 210 (q.m.).

- Combination in Cataulacus: Roger, 1863a: 210;

- combination in Cyphomyrmex: Mayr, 1884: 38; Forel, 1885a: 367.

- Status as species: Smith, F. 1862d: 413; Roger, 1863a: 210; Mayr, 1863: 428; Roger, 1863b: 40; Mayr, 1884: 38; Forel, 1885a: 368; Mayr, 1887: 557 (in key); Emery, 1890b: 55; Emery, 1894k: 58.

- Junior synonym of minutus: Roger, 1863b: 40.

- Junior synonym of rimosus: Emery, 1893h: 2; Forel, 1893e: 607; Forel, 1893g: 374; Dalla Torre, 1893: 150; Emery, 1894c: 224; Forel, 1895b: 137; Forel, 1899c: 40; Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 719; Gallardo, 1916d: 323; Emery, 1924d: 342; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 829; Kempf, 1966: 162; Kempf, 1972a: 93; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1410; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 147; Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 167.

- fuscula. Cyphomyrmex rimosus var. fuscula Emery, 1924d: 342.

- Unnecessary replacement name for fuscus Emery, 1894c: 225.

- Subspecies of rimosus: Borgmeier, 1927c: 126; Santschi, 1931e: 279; Santschi, 1933e: 118; Eidmann, 1936b: 85; Weber, 1940a: 411 (in key); Kusnezov, 1949d: 439; Kusnezov, 1957b: 10 (in key).

- Junior synonym of fuscus: Weber, 1958d: 260; Kempf, 1966: 162; Kempf, 1972a: 94.

- Junior synonym of rimosus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

- fuscus. Cyphomyrmex rimosus var. fuscus Emery, 1894c: 225 (w.) BRAZIL (Santa Catarina).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- [Note: Weber, 1958d: 260, cites 9w, 1q, 2m syntypes, and gives the collector’s name as Schmidt.]

- Type-locality: Brazil: Santa Catarina (no collector’s name).

- Type-depositories: MHNG, MSNG.

- Subspecies of rimosus: Forel, 1895b: 143; Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 721; Forel, 1911c: 295; Forel, 1912e: 188; Luederwaldt, 1918: 39; Weber, 1958d: 260; Kempf, 1966: 162; Kempf, 1972a: 94; Brandão, 1991: 339.

- Junior synonym of rimosus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 491; Bolton, 1995b: 168.

Taxonomic Notes

Longino (2004) provides the following concerning the status of this species:

Snelling and Longino (1992) distinguished three similar species, Cyphomyrmex hamulatus, Cyphomyrmex minutus, and rimosus, based on differences in size, pilosity, and extent of the median basal groove of the first gastral tergite. Subsequently I have not been able to differentiate these taxa. There is abundant geographic variation. In some localities it appears that there are discrete sympatric forms, but in other areas the distinction is blurred. For example, in Florida there are two discrete forms, a native species that is relatively small and an introduced species that is larger and darker. The key in Snelling and Longino would separate these into minutus and rimosus, respectively. In Costa Rica, specimens that are collected from open areas, usually by finding nests in the soil or foragers on the surface, are relatively larger and with longer scapes than specimens found in wet forest leaf litter, but the size distributions overlap. Until further evidence for discrete species is produced, I prefer to call them all C. rimosus.

This is a problem for Florida, where there are clearly two species, one native and one introduced. The introduced form is similar to the types of Emery's fuscus, from Brazil (fuscus was synonymized under rimosus by Snelling and Longino). Cyphomyrmex rimosus s.l. may be a polytypic species, in which the native form gradually changes as populations extend through Central and South America, such that the southernmost populations are reproductively isolated from the northernmost populations and remain separate when placed in sympatry through introduction. Alternatively, there could be a complex mosaic of cryptic species, with Florida just being a simplified and more visible example of what occurs throughout the range.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

ha il 2.° segmento del peduncolo poco piu largo che lungo e le sporgenze del torace forti e acute, specialmente Ie punte laterali del pronoto. La forma del peduncolo e descritta esattamente da Smith, ed. e quella sulla quale mi appoggio per stabilire la sinonimia del Meranoplus difformis con la forma descritta da Spinola.

Queen

il metanoto discende molto ripido e in linea quasi retta, se si guarda di profilo, ed e armato di un paio di piccoli denti o tubercoli; il peduncolo e piu largo che nella regina.

Male

il capo e relativamente stretto, con gli angoli posteriori acutissimi; il 2.° segmento del peduncolo meno di una volta e mezzo largo quanto e lungo.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- 2n = 32, karyotype = 28M+4A (Panama) (Murakami et al., 1998).

References

- Adams, R.M.M., Wells, R.L., Yanoviak, S.P., Frost, C.J., Fox, E.G.P. 2020. Interspecific Eavesdropping on Ant Chemical Communication. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8. (doi:10.3389/fevo.2020.00024).

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Atchison, R. A., Lucky, A. 2022. Diversity and resilience of seed-removing ant species in Longleaf Sandhill to frequent fire. Diversity 14, 1012 (doi:10.3390/d14121012).

- Baena, M.L., Escobar, F., Valenzuela, J.E. 2019. Diversity snapshot of green–gray space ants in two Mexican cities. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science 40, 239–250 (doi:10.1007/s42690-019-00073-y).

- Beckers R., Goss, S., Deneubourg, J.L., Pasteels, J.M. 1989. Colony size, communication and ant foraging Strategy. Psyche 96: 239-256 (doi:10.1155/1989/94279).

- Bruch, C. 1914. Catálogo sistemático de los formícidos argentinos. Rev. Mus. La Plata 19: 211-234 (page 217, Combination in Cyphomyrmex)

- Cantone S. 2017. Winged Ants, The Male, Dichotomous key to genera of winged male ants in the World, Behavioral ecology of mating flight (self-published).

- Cantone S. 2018. Winged Ants, The queen. Dichotomous key to genera of winged female ants in the World. The Wings of Ants: morphological and systematic relationships (self-published).

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- Deyrup, M. 1991. Exotic ants of the Florida Keys. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proc. 4th Sym. Nat. Hist. Bahamas: 15-22.

- Deyrup, M., Davis, L. & Cover, S. 2000. Exotic ants in Florida. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 126, 293-325.

- Emery, C. 1893j. Intorno ad alcune formiche della collezione Spinola. Boll. Mus. Zool. Anat. Comp. R. Univ. Torino 8(1 163: 1-3 (page 2, Combination in Cyphomyrmex)

- Emery, C. 1894d. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 26: 137-241 (page 224, queen described, Senior synonym of difformis)

- Fernández-Marín, H., Zimmerman, J.K., Wcislo, W.T. 2005. Acanthopria and Mimopriella parasitoid wasps (Diapriidae) attack Cyphomyrmex fungus-growing ants (Formicidae, Attini). Naturwissenschaften 93, 17–21 (doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0048-z).

- Forel, A. 1893h. Note sur les Attini. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 37: 586-607 (page 607, Senior synonym of difformis)

- Forel, A. 1912f. Formicides néotropiques. Part II. 3me sous-famille Myrmicinae Lep. (Attini, Dacetii, Cryptocerini). Mém. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 19: 179-209 (page 188, Combination in Atta (Cyphomyrmex))

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Gochnour, B.M., Suiter, D.R., Booher, D. 2019. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) fauna of the Marine Port of Savannah, Garden City, Georgia (USA). Journal of Entomological Science 54, 417-429 (doi:10.18474/jes18-132).

- Hamilton, N., Jones, T.H., Shik, J.Z., Wall, B., Schultz, T.R., Blair, H.A., Adams, R.M.M. 2018. Context is everything: mapping Cyphomyrmex-derived compounds to the fungus-growing ant phylogeny. Chemoecology 28, 137–144. (doi:10.1007/S00049-018-0265-5).

- Hanisch, P.E., Sosa-Calvo, J., Schultz, T.R. 2022. The last piece of the puzzle? Phylogenetic position and natural history of the monotypic fungus-farming ant genus Paramycetophylax (Formicidae: Attini). Insect Systematics and Diversity 6 (1): 11:1-17 (doi:10.1093/isd/ixab029).

- Herrera, H.W., Baert, L., Dekoninck, W., Causton, C.E., Sevilla, C.R., Pozo, P., Hendrickx, F. 2020. Distribution and habitat preferences of Galápagos ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Belgian Journal of Entomology, 93: 1–60.

- Hill, J.G. 2015. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Big Thicket Region of Texas. Midsouth Entomologist 8: 24-34.

- Ipser, R.M., Brinkman, M.A., Gardner, W.A., Peeler, H.B. 2004. A survey of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia. Florida Entomologist 87: 253-260.

- Lubertazzi, D. 2019. The ants of Hispaniola. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 162(2), 59-210 (doi:10.3099/mcz-43.1).

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Melo, T.S., Koch, E.B.A., Andrade, A.R.S., Travassos, M.L.O., Peres, M.C.L., Delabie, J.H.C. 2021. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in different green areas in the metropolitan region of Salvador, Bahia state, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology 82, e236269 (doi:10.1590/1519-6984.236269).

- Mera-Rodríguez, D., Serna, F., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lattke, J., Rabeling, C. 2020. A checklist of the non-leaf-cutting fungus-growing ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from Colombia, with new biogeographic records. Check List 16, 1205–1227 (doi:10.15560/16.5.1205).

- Meurgey, F. 2020. Challenging the Wallacean shortfall: A total assessment of insect diversity on Guadeloupe (French West Indies), a checklist and bibliography. Insecta Mundi 786: 1–183.

- Murakami, T.; Fujiwara, A.; Yoshida, M. C. 1999. Cytogenetics of ten ant species of the tribe Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Chromosome Science 2(3): 135-139 (page 135-139, Karyotype described)

- Nielsen, A., Atchison, R., Lucky, A. 2020. Effects of the invasive Little Fire Ant (Wasmannia auropunctata) on ant community composition on UF Campus. University of Florida | Journal of Undergraduate Research | Volume 22

- Ramos-Lacau, L. S., P. S. D. Silva, J. H. C. Delabie, S. Lacau, and O. C. Bueno. 2015. Nest Biology and Demography of the Fungus-Growing Ant Cyphomyrmex lectus Forel (Myrmicinae: Attini) at a Disturbed Area Located in Rio Claro-SP, Brazil. Sociobiology. 62:462-466. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v62i3.709

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Pr (page 1410, see also)

- Snelling, R. R.; Longino, J. T. 1992. Revisionary notes on the fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex, rimosus group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Attini). Pp. 479-494 in: Quintero, D., Aiello, A. (eds.) Insects of Panama and Mesoamerica: selected stu (page 491, Senior synonym of cochunae and fuscus ( and its junior synonyms curiapenis and fuscula))

- Spinola, M. 1851b. Compte rendu des Hyménoptères inédits provenants du voyage entomologique de M. Ghiliani dans le Para en 1846. Extrait des Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences de Turin (2) 13: 3-78 (page 49, worker, male described)

- Spinola, M. 1853. Compte rendu des Hyménoptères inédits provenants du voyage entomologique de M. Ghiliani dans le Para en 1846. Mem. R. Accad. Sci. Torino (2) 13: 19-94 (page 65, also described as new)

- Stuble, K.L., Kirkman, L.K., Carroll, C.R. 2010. Are red imported fire ants facilitators of native seed dispersal? Biological Invasions 12, 1661–1669.

- Tibcherani, M., Aranda, R., Mello, R.L. 2020. Time to go home: The temporal threshold in the regeneration of the ant community in the Brazilian savanna. Applied Soil Ecology 150, 103451 (doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.103451).

- Tschinkel, W.R. 2015. The architecture of subterranean ant nests: beauty and mystery underfoot. Journal of Bioeconomics 17:271–291 (DOI 10.1007/s10818-015-9203-6).

- Ulysséa, M.A., Brandão, C.R.F. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57, 217–224 (doi:10.1590/s0085-56262013005000002).

- Wetterer, J.K. 2021. Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of St. Vincent, West Indies. Sociobiology 68, e6725 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v68i2.6725).

- Wheeler, G. C. 1949 [1948]. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689 (page 668, larva described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Achury R., and A.V. Suarez. 2017. Richness and composition of ground-dwelling ants in tropical rainforest and surrounding landscapes in the Colombian Inter-Andean valley. Neotropical Entomology https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-017-0565-4

- Ahuatzin D. A., E. J. Corro, A. Aguirre Jaimes, J. E. Valenzuela Gonzalez, R. Machado Feitosa, M. Cezar Ribeiro, J. Carlos Lopez Acosta, R. Coates, W. Dattilo. 2019. Forest cover drives leaf litter ant diversity in primary rainforest remnants within human-modified tropical landscapes. Biodiversity and Conservation 28(5): 1091-1107.

- Alonso L. E., J. Persaud, and A. Williams. 2016. Biodiversity assessment survey of the south Rupununi Savannah, Guyana. BAT Survey Report No.1, 306 pages.

- Alonso L., M. Kaspari, and A. Alonso. 2001. Assessment of the Ants of the Lower Urubamba Region, Peru. Pp 87-93. In: Alsonso A, Dallmeier F, Campbell P, editors. Urubamba: The biodiversity of a Peruvian rainforest. SI/MAB Biodiversity Program-Smithsonian Institution. 204 p.

- Bestelmeyer B. T., and J. A. Wiens. 1996. The Effects of Land Use on the Structure of Ground-Foraging Ant Communities in the Argentine Chaco. Ecological Applications 6(4): 1225-40.

- Bieber A. G. D., P. D. Silva, and P. S. Oliveira. 2013. Attractiveness of Fallen Fleshy Fruits to Ants Depends on Previous Handling by Frugivores. Écoscience 20: 85-89.

- Blüthgen, N., M. Verhaagh, W. Goitia and N. Bluthgen. 2000. Ant nests in tank bromeliads an example of non-specific interaction. Insectes Sociaux 47:313-316

- Boer P. 2019. Ants of Saba, species list. Accessed on January 22 2019 at http://www.nlmieren.nl/websitepages/SPECIES%20LIST%20SABA.html

- Brandao, C.R.F. 1991. Adendos ao catalogo abreviado das formigas da regiao neotropical (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 35: 319-412.

- Bruch C. 1914. Catálogo sistemático de los formícidos argentinos. Revista del Museo de La Plata 19: 211-234.

- Calixto J. M. 2013. Lista preliminar das especies de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do estado do Parana, Brasil. Universidad Federal do Parana 34 pages.

- Cancino, E.R., D.R. Kasparan, J.M.A. Coronado Blanco, S.N. Myartseva, V.A. Trjapitzin, S.G. Hernandez Aguilar and J. Garcia Jimenez. 2010. Himenópteros de la Reserva El Cielo, Tamaulipas, México. Dugesiana 17(1):53-71

- Cardoso, D.C., T.G. Sobrinho and J.H. Schoereder. 2010. Ant community composition and its relationship with phytophysiognomies in a Brazilian Restinga. Insectes Sociaux 57:293-301

- Castano-Meneses G., R. De Jesus Santos, J. R. Mala Dos Santos, J. H. C. Delabie, L. L. Lopes, and C. F. Mariano. 2019. Invertebrates associated to Ponerine ants nests in two cocoa farming systems in the southeast of the state of Bahia, Brazil. Tropical Ecology 60: 52–61.

- Castano-Meneses, G., M. Vasquez-Bolanos, J. L. Navarrete-Heredia, G. A. Quiroz-Rocha, and I. Alcala-Martinez. 2015. Avances de Formicidae de Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

- Chacon de Ulloa P., A. M. Osorio-Garica, R. Achury, and C. Bermudez-Rivas. 2012. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del Bosque seco tropical (Bs-T) de la cuenca alta del rio Cauca, Colombia. Biota Colombiana 13(2): 165-181.

- Christianini A. V., A. J. Mayhé-Nunes, and P. S. Oliveira. 2012. Exploitation of Fallen Diaspores By Ants: Are There Ant-Plant Partner Choices? Biotropica 44: 360-367.

- Christianini A. V., and P. S. Oliveira. 2009. The relevance of ants as seed rescuers of a primarily bird-dispersed tree in the neotropical cerrado savanna. Oecologia 160: 735745.

- Claver S., S. L. Silnik, and F. F. Campon. 2014. Response of ants to grazing disturbance at the central Monte Desert of Argentina: community descriptors and functional group scheme. J Arid Land 6(1): 117?127.

- Clemes Cardoso D., and J. H. Schoereder. 2014. Biotic and abiotic factors shaping ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) assemblages in Brazilian coastal sand dunes: the case of restinga in Santa Catarina. Florida Entomologist 97(4): 1443-1450.

- Clemes Cardoso D., and M. Passos Cristiano. 2010. Myrmecofauna of the Southern Catarinense Restinga sandy coastal plain: new records of species occurrence for the state of Santa Catarina and Brazil. Sociobiology 55(1b): 229-239.

- Costa-Milanez C. B., F. F. Ribeiro, P. T. A. Castro, J. D. Majer, S. P. Ribeiro. 2015. Effct of fire on ant assemblages in Brazilian Cerrado in areas containing Vereda wetlands. Sociobiology 62(4): 494-505.

- Costa-Milanez C. B., G. Lourenco-Silva, P. T. A. Castro, J. D. Majer, and S. P. Ribeiro. 2014. Are ant assemblages of Brazilian veredas characterised by location or habitat type? Braz. J. Biol. 74(1): 89-99.

- Cuezzo, F. 1998. Formicidae. Chapter 42 in Morrone J.J., and S. Coscaron (dirs) Biodiversidad de artropodos argentinos: una perspectiva biotaxonomica Ediciones Sur, La Plata. Pages 452-462.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Del Toro, I., M. Vázquez, W.P. Mackay, P. Rojas and R. Zapata-Mata. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Tabasco: explorando la diversidad de la mirmecofauna en las selvas tropicales de baja altitud. Dugesiana 16(1):1-14.

- Emery C. 1890. Studii sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 22: 38-8

- Emery C. 1894. Estudios sobre las hormigas de Costa Rica. Anales del Museo Nacional de Costa Rica 1888-1889: 45-64.

- Emery C. 1894. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 26: 137-241.

- Escalante Gutiérrez J. A. 1993. Especies de hormigas conocidas del Perú (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Revista Peruana de Entomología 34:1-13.

- Favretto M. A., E. Bortolon dos Santos, and C. J. Geuster. 2013. Entomofauna from West of Santa Catarina State, South of Brazil. EntomoBrasilis 6 (1): 42-63.

- Fernandes I., and J. de Souza. 2018. Dataset of long-term monitoring of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the influence areas of a hydroelectric power plant on the Madeira River in the Amazon Basin. Biodiversity Data Journal 6: e24375.

- Fernandes T. T., R. R. Silva, D. Rodrigues de Souza-Campana, O. Guilherme Morais da Silva, and M. Santina de Castro Morini. 2019. Winged ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) presence in twigs on the leaf litter of Atlantic Forest. Biota Neotropica 19(3): http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1676-0611-bn-2018-0694

- Fernandes T. T., W. Dattilo, R. R. Silva, P. Luna, C. M. Oliveira, and M. Santina de Castro Morini. 2019. Ant occupation of twigs in the leaf litter of the Atlantic Forest: influence of the environment and external twig structure. Tropical Conservation Science 12: 1-9.

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fernández F., E. E. Palacio, W. P. Mackay, and E. S. MacKay. 1996. Introducción al estudio de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Colombia. Pp. 349-412 in: Andrade M. G., G. Amat García, and F. Fernández. (eds.) 1996. Insectos de Colombia. Estudios escogidos. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 541 pp

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Fichaux M., B. Bechade, J. Donald, A. Weyna, J. H. C. Delabie, J. Murienne, C. Baraloto, and J. Orivel. 2019. Habitats shape taxonomic and functional composition of Neotropical ant assemblages. Oecologia 189(2): 501-513.

- Field Museum Collection, Chicago, Illinois (C. Moreau)

- Fontenla Rizo J. L. 1993. Composición y estructura de comunidades de hormigas en un sistema de formaciones vegetales costeras. Poeyana. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba 441: 1-19.

- Fontenla Rizo J. L. 1993. Mirmecofauna de Isla de la Juventud y de algunos cayos del archipielago cubano. Poeyana. Instituto de Ecologia y Sistematica, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba 444:1-7.

- Fontenla Rizo J. L., and L. M. Hernández. 1993. Relaciones de coexistencia en comunidades de hormigas en un agroecosistema de caña de azúcar. Poeyana. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba 438: 1-16.

- Forel A. 1897. Quelques Formicides de l'Antille de Grenada récoltés par M. H. H. Smith. Transactions of the Entomological Society of London. 1897: 297-300.

- Forel A. 1908. Catálogo systemático da collecção de formigas do Ceará. Boletim do Museu Rocha 1(1): 62-69.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Galkowski C. 2016. New data on the ants from the Guadeloupe (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Bull. Soc. Linn. Bordeaux 151, 44(1): 25-36.

- Gallardo A. 1916. Notes systématiques et éthologiques sur les fourmis attines de la République Argentine. Anales del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Buenos Aires 28: 317-344.

- Garcia-Martinez M. A., V. Vanoye-Eligio, O. R. Leyva-Ovalle, P. Zetina-Cordoba, M. J. Aguilar-Mendez, and M. Rosas-Mejia. 2019. Diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a sub-montane and sub-tropical cityscape of Northeastern Mexico. Sociobiology 66(3): 440-447.

- Gove, A. D., J. D. Majer, and V. Rico-Gray. 2009. Ant assemblages in isolated trees are more sensitive to species loss and replacement than their woodland counterparts. Basic and Applied Ecology 10: 187-195.

- INBio Collection (via Gbif)

- Jacquemin J., T. Drouet, T. Delsinne, Y. Roisin, and M. Leponce. 2012. Soil properties only weakly affect subterranean ant distribution at small spatial scales. Applied Soil Ecology 62: 163-169.

- Jaffe, K., Mauleon, H. and Kermarrec A. 1990. Predatory Ants of Diaprepes Abbreviatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) In Citrus Groves In Martinique and Guadeloupe, F.W.I. Florida Entomologist. 73(4):684-687.

- Jaffe, Klaus and Lattke, John. 1994. Ant Fauna of the French and Venezuelan Islands in the Caribbean in Exotic Ants, editor D.F. Williams. 182-190.

- Kaspari M. 1996. Litter ant patchiness at the 1-m 2 scale: disturbance dynamics in three Neotropical forests. Oecologia 107: 265-273.

- Kaspari M., D. Donoso, J. A. Lucas, T. Zumbusch, and A. D. Kay. 2012. Using nutritional ecology to predict community structure: a field test in Neotropical ants. Ecosphere 3(11): art.93.

- Kempf W. W. 1961. A survey of the ants of the soil fauna in Surinam (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Studia Entomologica 4: 481-524.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Kusnezov N. 1949. El género Cyphomyrmex (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) en la Argentina. Acta Zoologica Lilloana 8: 427-456.

- Kusnezov N. 1952. El género Camponotus en la Argentina (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Acta Zoologica Lilloana 12: 183-252.

- Kusnezov N. 1953. La fauna mirmecológica de Bolivia. Folia Universitaria. Cochabamba 6: 211-229.

- Kusnezov N. 1963. Zoogeografia de las hormigas en sudamerica. Acta Zoologica Lilloana 19: 25-186

- Kusnezov N. 1978. Hormigas argentinas: clave para su identificación. Miscelánea. Instituto Miguel Lillo 61:1-147 + 28 pl.

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/

- Luederwaldt H. 1918. Notas myrmecologicas. Rev. Mus. Paul. 10: 29-64.

- Lutinski J. A., B. C. Lopes, and A. B. B.de Morais. 2013. Diversidade de formigas urbanas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de dez cidades do sul do Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 13(3): 332-342.

- Maes, J.-M. and W.P. MacKay. 1993. Catalogo de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia 23.

- Mann W. M. 1916. The Stanford Expedition to Brazil, 1911, John C. Branner, Director. The ants of Brazil. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 60: 399-490

- Mirmecofauna de la reserva ecologica de San Felipe Bacalar

- Murakami T., A. Fujiwara,and M. C. Yoshida. 1999. Cytogenetics of ten ant species of the tribe Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Chromosome Science 2(3): 135-139.

- Nascimento Santos M., J. H. C. Delabie, and J. M. Queiroz. 2019. Biodiversity conservation in urban parks: a study of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Rio de Janeiro City. Urban Ecosystems https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00872-8

- Nunes F. A., G. B. Martins Segundo, Y. B. Vasconcelos, R. Azevedo, and Y. Quinet. 2011. Ground-foraging ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and rainfall effect on pitfall trapping in a deciduous thorn woodland (Caatinga), Northeastern Brazil. Rev. Biol. Trop. 59 (4): 1637-1650.

- Osorio Rosado J. L, M. G. de Goncalves, W. Drose, E. J. Ely e Silva, R. F. Kruger, and A. Enimar Loeck. 2013. Effect of climatic variables and vine crops on the epigeic ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Campanha region, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Insect Conserv 17: 1113-1123.

- Philpott, S.M., P. Bichier, R. Rice, and R. Greenberg. 2007. Field testing ecological and economic benefits of coffee certification programs. Conservation Biology 21: 975-985.

- Pignalberi C. T. 1961. Contribución al conocimiento de los formícidos de la provincia de Santa Fé. Pp. 165-173 in: Comisión Investigación Científica; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Argentina) 1961. Actas y trabajos del primer Congreso Sudamericano de Zoología (La Plata, 12-24 octubre 1959). Tomo III. Buenos Aires: Librart, 276 pp.

- Quiroz-Robledo L., and J. Valenzuela-Gonzalez. 1995. A comparison of ground ant communities in a tropical rainforest and adjacent grassland in Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist 20(2): 203-213.

- Radoszkowsky O. 1884. Fourmis de Cayenne Française. Trudy Russkago Entomologicheskago Obshchestva 18: 30-39.

- Ramirez M., J. Montoya-Lerma, and I. Armbrecht. 2010. Fodder banks: Does cyclic pruning influence soil ant richness (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)? AVANCES EN INVESTIGACIÓN AGROPECUARIA 13(3): 47-66.

- Rojas P., C. Fragoso, and W. P. MacKay. 2014. Ant communities along a gradient of plant succession in Mexican tropical coastal dunes. Sociobiology 61(2): 119-132.

- Rosa da Silva R. 1999. Formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do oeste de Santa Catarina: historico das coletas e lista atualizada das especies do Estado de Santa Catarina. Biotemas 12(2): 75-100.

- Rosado J. L. O., M. G. de Gonçalves, W. Dröse, E. J. E. e Silva, R. F. Krüger, R. M. Feitosa, and A. E. Loeck. 2012. Epigeic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in vineyards and grassland areas in the Campanha region, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Check List, Journal of species lists and distribution 8(6): 1184-1189.

- Rosumek, F.B., M.A. Ulyssea, B.C. Lopes, J. Steiner. 2008. Formigas de solo e de bromélias em uma área de Mata Atlântica, Ilha de Santa Catarina, sul do Brasil: Levantamento de espécies e novos registros. Revista Biotemas 21(4):81-89.

- Santoandre S., J. Filloy, G. A. Zurita, and M. I. Bellocq. 2019. Ant taxonomic and functional diversity show differential response to plantation age in two contrasting biomes. Forest Ecology and Management 437: 304-313.

- Santschi F. 1931. Contribution à l'étude des fourmis de l'Argentine. Anales de la Sociedad Cientifica Argentina. 112: 273-282.

- Santschi F. 1933. Fourmis de la République Argentine en particulier du territoire de Misiones. Anales de la Sociedad Cientifica Argentina. 116: 105-124.

- Smith M. A., W. Hallwachs, D. H. Janzen. 2014. Diversity and phylogenetic community structure of ants along a Costa Rican elevational gradient. Ecography 37(8): 720-731.

- Solomon, S.E. and A.S. Mikheyev. 2005. The ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) fauna of Cocos Island, Costa Rica. Florida Entomologist 88(4):415-423

- Sosa-Calvo J. 2007. Ants of the leaf litter of two plateaus in Eastern Suriname. In Alonso, L.E. and J.H. Mol (eds.). 2007. A rapid biological assessment of the Lely and Nassau plateaus, Suriname (with additional information on the Brownsberg Plateau). RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment 43. Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA.

- Torres J.A. 1984. Niches and Coexistence of Ant Communities in Puerto Rico: Repeated Patterns. Biotropica 16(4): 284-295.

- Ulyssea M. A., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57(2): 217224.

- Ulyssea M.A., C. E. Cereto, F. B. Rosumek, R. R. Silva, and B. C. Lopes. 2011. Updated list of ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) recorded in Santa Catarina State, southern Brazil, with a discussion of research advances and priorities. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(4): 603-611.

- Ulysséa M. A., C. R. F. Brandão. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57(2): 217-224.

- Varela-Hernandez, F., M. Rocha-Ortega, R. W. Jones, and W. P. Mackay. 2016. Insectos: Hormigas (Formicidae) del estado de Queretaro, Mexico. Pages 397-404 in W. Jones., and V. Serrano-Cardenas, editors. Historia Natural de Queretaro. Universidad Autonoma de Queretaro, Mexico.

- Vasconcelos, H.L., J.M.S. Vilhena, W.E. Magnusson and A.L.K.M. Albernaz. 2006. Long-term effects of forest fragmentation on Amazonian ant communities. Journal of Biogeography 33:1348-1356

- Vittar, F. 2008. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Mesopotamia Argentina. INSUGEO Miscelania 17(2):447-466

- Vittar, F., and F. Cuezzo. "Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina." Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina (versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471) 67, no. 1-2 (2008).

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Weber N. A. 1937. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part l. New forms. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 7: 378-409.

- Weber N. A. 1938. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part IV. Additional new forms. Part V. The Attini of Bolivia. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 9: 154-206.

- Weber N. A. 1938. The food of the giant toad, Bufo marinus (L.), in Trinidad and British Guiana with special reference to the ants. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 31: 499-503.

- Weber N. A. 1941. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VII. The Barro Colorado Island, Canal Zone, species. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 12: 93-130.

- Weber N. A. 1945. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VIII. The Trinidad, B. W. I., species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 16: 1-88.

- Weber N. A. 1946. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part IX. The British Guiana species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 17: 114-172.

- Weber N. A. 1947. Lower Orinoco River fungus-growing ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae, Attini). Boletín de Entomologia Venezolana 6: 143-161.

- Weber N. A. 1948. Studies on the fauna of Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire and the Venezuelan islands: No. 14. Ants from the Leeward Group and some other Caribbean localities. Natuurwetenschappelijke Studiekring voor Suriname en de Nederlandse Antillen 5: 78-86.

- Weber N. A. 1952. Biological notes on Dacetini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). American Museum Novitates 1554: 1-7.

- Weber N. A. 1958. Some attine synonyms and types (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 60: 259-264.

- Weber, Neal A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79:141-145.

- Weber, Neal A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants. Entomological News. 79(6): 141-145.

- Weber, Neil A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79(6):141-145.

- Wheeler G. C. 1949. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689.

- Wheeler W. M. 1905. The ants of the Bahamas, with a list of the known West Indian species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21: 79-135.

- Wheeler W. M. 1907. A collection of ants from British Honduras. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 23: 271-277.

- Wheeler W. M. 1907. The fungus-growing ants of North America. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 23: 669-807.

- Wheeler W. M. 1922. The ants of Trinidad. American Museum Novitates 45: 1-16.

- Wheeler W. M. 1925. Neotropical ants in the collections of the Royal Museum of Stockholm. Arkiv för Zoologi 17A(8): 1-55.

- Zolessi L. C. de, Y. P. Abenante, and M. E. de Philippi. 1988. Lista sistematica de las especies de Formicidos del Uruguay. Comun. Zool. Mus. Hist. Nat. Montev. 11: 1-9.

- Zolessi L. C. de; Y. P. de Abenante, and M. E. Philippi. 1989. Catálogo sistemático de las especies de Formícidos del Uruguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Montevideo: ORCYT Unesco, 40 + ix pp.

- da Silva de Oliveira A. B., and F. A. Schmidt. 2019. Ant assemblages of Brazil nut trees Bertholletia excelsa in forest and pasture habitats in the Southwestern Brazilian Amazon. Biodiversity and Conservation 28(2): 329-344.

- de Zolessi, L.C., Y.P. de Abenante and M.E. Phillipi. 1989. Catalago Systematico de las Especies de Formicidos del Uruguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Oficina Regional de Ciencia y Technologia de la Unesco para America Latina y el Caribe- ORCYT. Montevideo, Uruguay

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Invasive

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- South subtropical

- South temperate

- Diapriid wasp Associate

- Host of Acanthopria spp.

- Host of Mimopriella sp.

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 1

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 2

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 3

- Host of Acanthopria sp. 4

- FlightMonth

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Attini

- Cyphomyrmex

- Cyphomyrmex rimosus

- Myrmicinae species

- Attini species

- Cyphomyrmex species

- Ssr