Acromyrmex octospinosus

| Acromyrmex octospinosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Acromyrmex |

| Species: | A. octospinosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Acromyrmex octospinosus (Reich, 1793) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Acromyrmex octospinosus is a host species of the social parasite Acromyrmex insinuator. Note that the taxonomic status of this species was recently revised by Mera-Rodríguez et al. (2024).

| At a Glance | • Highly invasive |

Identification

Median pronotal spines usually present and distinct, occasionally reduced or absent; head tapering behind eyes; head width less than or equal to 1.7 mm.

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 23.133° to -14.81°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Brazil, Costa Rica (type locality), Cuba (type locality), Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana (type locality), Greater Antilles, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico (type locality), Nicaragua, Panama, Peru (type locality), Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Boulogne et al. (2018) - Acromyrmex octospinosus causes serious damage to fields crops, pastures and plantations due to their foraging activities for its symbiotic fungus cultivation (Pérez et al 2011). Estimated damage was, for example, several million dollars per year in USA and Brazil (Cameron & Riggs 1985). A. octospinosus is native to South and Central America and exotic to Guadeloupe. This species was introduced in Guadeloupe in 1954 and progressively colonized the entire territory (Boulogne et al 2014), causing ongoing damage in both agricultural and protected areas. The 1995 cyclone favored ant invasion in natural areas where some plant species, such as the endemic arborescent ferns of the genus Cyathea, are now threatened and might completely disappear (Boulogne et al 2014). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) classifies this ant among the most serious pests of tropical and subtropical America (Pollard 1982).

Fernandez- Marin et al. (2003) - Incipient nests of Acromyrmex octospinosus have only 3-7 workers.

Nehring et al. (2015) - This species is parastized by queens of Acromyrmex insinuator.

Weber (1958) - The springtail species Cyphoderus inaequalis Folsom (Lepidocyrtidae: Cyphoderinae) is known from nests of this ant.

Wetterer (1993) - Acromyrmex volcanus is common in mature wet forest on the Atlantic slope of Costa Rica, occurring from sea level to about 1000m elevation. It is one of the most common and conspicuous attines in lowland primary forest, giving way to Atta in second growth and more open habitats.

J.T. Longino - At La Selva Biological Station, A. volcanus workers forage on the ground but nests are arboreal. When I first encountered the species in 1985, I was mystified by the large workers cutting fallen flowers on the forest floor and carrying them up tree trunks. Later, while climbing a tall Pentaclethra tree at La Selva, I was standing in the first major fork, 20m above the forest floor, when Acromyrmex workers suddenly appeared around my feet. I found a basketball-sized nest, with a large fungus garden, embedded in the accumulated canopy soil beneath the epiphyte layer in the fork. Subsequent observations by Wetterer and others have repeatedly confirmed the arboreal nesting habits at La Selva, but at elevations above 500m A. volcanus nests at ground level (Wetterer, pers. comm.). Wetterer (1993) reports quantitative data on the foraging and nesting ecology of A. volcanus at La Selva.

Reproduction

Liberti et al. (2018) studied sperm competition in this species. Queens of A. octospinosus (as A. echinatior) mate with multiple males. An earlier study (Liberti et al. 2016) found that queens produce reproductive tract fluid that enhances sperm motility. This increases the possibility that the subsequently stored sperm is viable. This current study found sperm motility increased when exposed to other male ejaculates. This increased activity was similar to what was observed with exposure to reproductive tract fluid in queens. Liberti et al. concluded "Our results suggest that ant sperm respond via a self–non-self recognition mechanism to similar or shared molecules expressed in the reproductive secretions of both sexes. Lower sperm motility in the presence of own seminal fluid indicates that enhanced motility is costly and may trade-off with sperm viability during sperm storage, consistent with studies in vertebrates. Our results imply that ant spermatozoa have evolved to adjust their energetic expenditure during insemination depending on the perceived level of sperm competition."

Interactions with other organisms

Many organisms use chemicals to deter enemies. Some spiders can modify the composition of their silk to deter predators from climbing onto their webs. The Malaysian golden orb-weaver Nephila antipodiana (Walckenaer) produces silk containing an alkaloid (2-pyrrolidinone) that functions as a defense against ant invasion. Ants avoid silk containing this chemical. In the present study, we test the generality of ants' silk avoidance behavior in the field. We introduced three ant species to the orb webs of Nephila clavipes (Linnaeus) in the tropical rainforest of La Selva, Costa Rica. We found that predatory army ants (Eciton burchellii) as well as non-predatory leaf-cutting ants (Atta cephalotes and A. octospinosus (as Acromyrmex volcanus)) avoided adult N. clavipes silk, suggesting that an additional species within genus Nephila may possess ant-deterring silk. Our field assay also suggests that silk avoidance behavior is found in multiple ant species.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the fungus Aspergillus flavus (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (as Acromyrmex echinatior; encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

- This species is a host for the fungus Ophiocordyceps kniphofioides (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the nematode Steinerema carpocapsae (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (multiple encounter modes; indirect transmission; transmission outside nest).

Life History Traits

- Mean colony size: 50,000 (Beckers et al., 1989)

- Foraging behaviour: mass recruiter (Beckers et al., 1989)

Castes

Images from AntWeb

Worker

| |

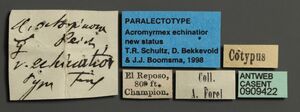

| Paralectotype of Acromyrmex echinatior. Worker. Specimen code casent0909422. Photographer Will Ericson, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MHNG, Geneva, Switzerland. |

| |

| Lectotype of Atta octospinosa echinatior. Worker (major/soldier). Specimen code casent0909421. Photographer Will Ericson, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MHNG, Geneva, Switzerland. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code inbiocri001284242. Photographer Estella Ortega, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by JTLC. |

Queen

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code inbiocri001283113. Photographer Estella Ortega, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by JTLC. |

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code inbiocri001283113. Photographer Estella Ortega, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | |

Male

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code inbiocri001283114. Photographer Estella Ortega, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by JTLC. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- octospinosus. Formica octospinosa Reich, 1793: 132 (w.) FRENCH GUIANA.

- Type-material: holotype (?) worker.

- [Note: no indication of number of specimens is given.]

- Type-locality: French Guiana: Cayenne (Le Blond).

- Type-depository: unknown (no material known to exist).

- [Notes (i): specimen(s) possibly in MNHN as Reich is attributed to the Natural History Society of Paris; (ii) G.C. Reich is not mentioned in Horn & Kahle, 1936, 1937.]

- Forel, 1893e: 590 (s.q.m.); Wheeler, G.C. 1949: 674 (l.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1986d: 496 (l.).

- Combination in Atta: Emery, 1892b: 163;

- combination in Atta (Acromyrmex): Forel, 1893e: 590;

- combination in Acromyrmex: Mann, 1916: 454.

- Status as species: Forel, 1893e: 590 (redescription); André, 1893b: 152; Dalla Torre, 1893: 153; Emery, 1894c: 220; Forel, 1895b: 139; Forel, 1899c: 34; Forel, 1905b: 157; Emery, 1905c: 44; Wheeler, W.M. 1905b: 130; Forel, 1907e: 2; Forel, 1908b: 42; Forel, 1908e: 69; Forel, 1912e: 181; Wheeler, W.M. 1913b: 495; Santschi, 1913h: 41; Mann, 1916: 454; Wheeler, W.M. 1916d: 326; Crawley, 1916b: 373; Wheeler, W.M. 1922c: 13; Emery, 1924d: 350; Santschi, 1925a: 391 (in key); Borgmeier, 1927c: 134; Wheeler, W.M. 1933a: 63; Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 15, 69; Santschi, 1939e: 319 (in key); Santschi, 1939f: 166; Weber, 1941b: 125; Weber, 1945: 62; Weber, 1946b: 154; Brown, 1957e: 236; Gonçalves, 1961: 157; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Alayo, 1974: 42; Cherrett & Cherrett, 1989: 51; Bolton, 1995b: 56; Branstetter & Sáenz, 2012: 257; Fernández, et al. 2015: 70 (redescription); Fernández & Serna, 2019: 834.

- Senior synonym of guentheri: Emery, 1894c: 220; Forel, 1899c: 34, Santschi, 1913h: 41; Emery, 1924d: 350; Borgmeier, 1927c: 134; Gonçalves, 1961: 157; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 56; Fernández, et al. 2015: 71.

- Senior synonym of pallida Crawley: Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 70; Gonçalves, 1961: 157; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 56; Fernández, et al. 2015: 71.

- Distribution: Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Mexico, Trinidad, Venezuela.

- Current subspecies: nominal plus cubanus, ekchuah, inti.

- cubanus. Acromyrmex octospinosus subsp. cubanus Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 74 (s.) CUBA.

- Type-material: 9 syntype workers.

- Type-localities: 6 workers Cuba: Cojimar (W.M. Wheeler & C.F. Baker) (invalid restriction of type-locality by Kempf, 1972a: 14; no lectotype designated), 3 workers Cuba: Havana (G. Aguayo).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Mera‐Rodríguez et al. 2024: 12.

- Distribution: Cuba.

- ekchuah. Acromyrmex octospinosus subsp. ekchuah Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 73 (s.) MEXICO (Yucatan).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated, “numerous”).

- Type-localities: Mexico: Yucatan, Oxkutzab, Puz Cave (A.S. Pearse) (invalid restriction of type-locality by Kempf, 1972a: 14; no lectotype designated), Mexico: Yucatan, Oxkutzab, Gongora Cave (A.S. Pearse), Yucatan, Oxkutzab, Tiz Cave (A.S. Pearse), Yucatan, Merida, San Bulha Cave (A.S. Pearse), Yucatan, Calcehtok, Xkyc Cave (A.S. Pearse), Yucatan, Tizcacal, Luchil Cave (A.S. Pearse).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Wheeler, W.M. 1938: 252 (footnote); Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Mera‐Rodríguez et al. 2024: 12.

- Distribution: Mexico.

- inti. Acromyrmex octospinosus subsp. inti Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 72 (s.) PERU.

- Type-material: 4 syntype workers.

- Type-locality: Peru: San Bartolome (C.T. Brues).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 55; Bezděčková, et al. 2015: 114.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Mera‐Rodríguez et al. 2024: 12.

- Distribution: Peru.

- echinatior. Atta (Acromyrmex) octospinosa var. echinatior Forel, 1899c: 34 (w.q.) MEXICO (Chihuahua), GUATEMALA, COSTA RICA, PANAMA.

- Type-material: lectotype worker (by designation of Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998: 461), paralectotype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: lectotype Guatemala: Vera Paz, Senahu, El Reposo, Zapota, 800 ft (Champion); paralectotypes: with same data and from other original syntype localities.

- [Note: other original syntype localities: Mexico: Chihuahua, Montezuma (Cockerell), Costa Rica: Volcán de Irazu (Rogers), Panama: Volcán de Chiriqui, Bugaba (Champion) (invalid restriction of type-locality by Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 72 (in text); no lectotype designated).]

- Type-depository: MHNG.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 72 (m.).

- Combination in Acromyrmex: Emery, 1924d: 350.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Emery, 1905c: 44.

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Forel, 1912e: 181; Emery, 1924d: 350; Santschi, 1925a: 391 (in key); Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 71; Wheeler, W.M. 1938: 252; Santschi, 1939e: 319 (in key); Santschi, 1939f: 166 (in key); Weber, 1941b: 125; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Status as species: Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998: 460; Branstetter & Sáenz, 2012: 257.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Mera‐Rodríguez et al. 2024: 12.

- Distribution: Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama.

- volcanus. Acromyrmex octospinosus subsp. volcanus Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 73 (s.) COSTA RICA.

- Type-material: 7 syntype workers.

- Type-locality: Costa Rica: Volcán de Barba, Finca Hamburgo (C.W. Dodge).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 57 (error).

- Status as species: Wetterer, 1993: 66.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Mera‐Rodríguez et al. 2024: 12.

- Distribution: Costa Rica.

- guentheri. Atta (Acromyrmex) guentheri Forel, 1893e: 594 (s.w.q.m.) TRINIDAD, VENEZUELA.

- Type-material: syntype workers, syntype queens, syntype males (numbers not stated).

- Type-localities: Trinidad: (no further data) (Günther), Trinidad: (no further data) (F.W. Urich), Venezuela: (no further data) (F. Meinert).

- Type-depository: MHNG (perhaps also ZMUC).

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Emery, 1894c: 220; Forel, 1899c: 34; Santschi, 1913h: 41; Emery, 1924d: 350; Borgmeier, 1927c: 134; Gonçalves, 1961: 157; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 55; Fernández, et al. 2015: 71.

- pallida. Acromyrmex octospinosa var. pallida Crawley, 1921: 92 (s.w.) GUYANA.

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: Guyana (“British Guiana”): Issororo, 1918, no. 422 (Bodkin).

- Type-depository: BMNH.

- [Unresolved junior secondary homonym of Oecodoma pallida Smith, F. 1858b: 187 (Bolton, 1995b: 56).]

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Santschi, 1925a: 359; Santschi, 1939e: 319 (in key); Santschi, 1939f: 166 (in key).

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 70; Gonçalves, 1961: 157; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 56; Fernández, et al. 2015: 71.

Type Material

Atta octospinosa echinatior

- Schultz et al. (1998) - LECTOTYPE: Major worker. Guatemala: Senahuen Vera Paz, El Reposo, Zapote, 800 ft. (Champion). A. Forel Collection, Muséum d’Histoire naturelle, Geneva, Switzerland. Paratypes examined: 2 minor workers: Guatemala: Senahuen Vera Paz, El Reposo, 800 ft. (Champion). 1 alate and 1 dealate female: Panama: Volcan de Chiriquí, 25–1000 ft. (Champion). 2 alate females: Panama: Bugaba (Champion).

The list of specimens published in Forel’s (1899) description includes two workers, one from Guatemala and one from Costa Rica, the latter now apparently lost. Forel (1899) did not designate a holotype; five pins (seven specimens) in the syntype series bear the designation “type” written in Forel’s hand. Affixed to two of Forel’s syntype pins, one bearing a single major worker, the other bearing two females, are red “Typus” labels, but these may have been added subsequently and at any rate have no formal standing. Wheeler (1937) designated the type locality of A. octospinosus echinatior as Volcan de Chiriquí, Panama, the collection locality of two of Forel’s syntype females, but did not designate a lectotype. We have chosen to ignore this action and to designate the only remaining major worker in Forel’s syntype series as the lectotype for two important reasons: (1) species concepts in Acromyrmex are based entirely upon the characters of major workers and (2) Forel’s syntype females vary in size and collection locality, raising the possibility that they represent multiple species.

Description

Genetics

Acromyrmex octospinosus (as A. echinatior) has had their entire genome sequenced.

Palomeque et al. (2015) found class II mariner elements, a form of transposable elements, in the genome of this ant.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- 2n = 38, karyotype = 8M+6SM+14ST+10A (Brazil) (Barros et al., 2016) (as Acromyrmex echinatior).

References

- Adams, R.M.M., Wells, R.L., Yanoviak, S.P., Frost, C.J., Fox, E.G.P. 2020. Interspecific Eavesdropping on Ant Chemical Communication. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8. (doi:10.3389/fevo.2020.00024).

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Barros, L.A.C., Aguiar, H.J.A.C., Teixeira, G.C., Souza, D.J., Delabie, J.H.C., Mariano, C.S.F. 2021. Cytogenetic studies on the social parasite Acromyrmex ameliae (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) and its hosts reveal chromosome fusion in Acromyrmex. Zoologischer Anzeiger 293, 273–281 (doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2021.06.012).

- Beckers R., Goss, S., Deneubourg, J.L., Pasteels, J.M. 1989. Colony size, communication and ant foraging Strategy. Psyche 96: 239-256 (doi:10.1155/1989/94279).

- Billen, J.P.J. 2019. Diversidad y morfología de las glándulas exocrinas en las hormigas. Pp. 165-174 in: Fernández, F., Guerrero, R.J., Delsinne, T. (eds.) 2019d. Hormigas de Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1198 pp.

- Billen, J., Khalife, A., Ito, F., Anh, N.D., Esteves, F.A. 2021. The basitarsal sulcus gland, a novel exocrine structure in ants. Arthropod Structure, Development 61, 101041 (doi:10.1016/j.asd.2021.101041).

- Borowiec, M.L. 2019. Convergent evolution of the army ant syndrome and congruence in big-data phylogenetics. Systematic Biology 68, 642–656 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy088).

- Boulogne, I., L. Desfontaines, H. Ozier-Lafontaine, and G. Loranger-Merciris. 2018. Sustainable Management of Acromyrmex octospinosus (Reich): How Botanical Extracts Should Promote an Ecofriendly Control Strategy. Sociobiology. 65:348-357. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v65i3.1640

- Branstetter, M.G., Danforth, B.N., Pitts, J.P., Faircloth, B.C., Ward, P.S., Buffington, M.L., Gates, M.W., Kula, R.R., Brady, S.G. 2017. Phylogenomic insights into the evolution of stinging wasps and the origins of ants and bees. Current Biology 27, 1019–1025 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.027).

- Brown, M.J.F., Bonhoeffer, S. 2003. On the evolution of claustral colony founding in ants. Evolutionary Ecology Research 5: 305–313.

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- Casacci, L.P., Barbero, F., Slipinski, P., Witek, M. 2021. The inquiline ant Myrmica karavajevi uses both chemical and vibroacoustic deception mechanisms to integrate into its host colonies. Biology 10, 654 (doi:10.3390/ biology10070654)..

- Chernyshova, A.M. 2021. A genetic perspective on social insect castes: A synthetic review and empirical study. M.S. thesis, The University of Western Ontario. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7771.

- Silva, J.R.da, Souza, A.Z.de, Pirovani, C.P., Costa, H., Silva, A., Dias, J.C.T., Delabie, J.H.C., Fontana, R. 2018. Assessing the proteomic activity of the venom of the ant Ectatomma tuberculatum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ectatomminae). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2018, 1–11 (doi:10.1155/2018/7915464).

- Dahan, R.A., Grove, N.K., Bollazzi, M., Gerstner, B.P., Rabeling, C. 2021. Decoupled evolution of mating biology and social structure in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 76, 7 (doi:10.1007/s00265-021-03113-1).

- de Bekker, C., Will, I., Das, B., Adams, R.M.M. 2018. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and their parasites: effects of parasitic manipulations and host responses on ant behavioral ecology. Myrmecological News 28: 1-24 (doi:10.25849/myrmecol.news_028:001).

- de la Mora, A., Sankovitz, M., Purcell, J. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies. Myrmecological News 30: 53-71 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:053).

- Dekoninck, W., Wauters, N., Delsinne, T. 2019. Capitulo 35. Hormigas invasoras en Colombia. Hormigas de Colombia.

- Emery, C. 1892c [1891]. Note sinonimiche sulle formiche. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 23: 159-167 (page 163, Combination in Atta)

- Emery, C. 1894d. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bull. Soc. Entomol. Ital. 26: 137-241 (page 220, senior synonym of guentheri)

- Emery, C. 1924f [1922]. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Myrmicinae. [concl.]. Genera Insectorum 174C: 207-397 (page 350, Combination in Acromyrmex)

- Farder-Gomes, C.F., Oliveira, M.A., Castro Della Lucia, T.M., Serrão, J.E. 2019. Morphology of the ovary and spermatheca of the leafcutter ant Acromyrmex rugosus queens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 102, 515-519 (doi:10.1653/024.102.0312).

- Forel, A. 1893h. Note sur les Attini. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 37: 586-607 (page 590, soldier, queen, male described, Combination in Atta (Acromyrmex))

- Forel, A. 1899d. Formicidae. [part]. Biol. Cent.-Am. Hym. 3: 25-56 (page 34, worker, queen described)

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Gonçalves, C. R. 1961. O genero Acromyrmex no Brasil (Hym. Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 4: 113-180 (page 157, see also)

- Hamilton, N., Jones, T.H., Shik, J.Z., Wall, B., Schultz, T.R., Blair, H.A., Adams, R.M.M. 2018. Context is everything: mapping Cyphomyrmex-derived compounds to the fungus-growing ant phylogeny. Chemoecology 28, 137–144. (doi:10.1007/S00049-018-0265-5).

- Jacobs, S. 2020. Population genetic and behavioral aspects of male mating monopolies in Cardiocondyla venustula (Ph.D. thesis).

- Landero-Torres, I., Garcia-Martinez, M.A., Galindo-Tovar, M.E., Leyva-Ovalle, O.R., Lee-Espinosa, H.E., Murguia-Gonzalez, J., Negrin-Ruiz, J. 2014. Alpha diversity of the myrmecofauna of the Natural Protected Area Metlac from Fortin, Veracruz, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist 39: 541-553.

- Lau, M.K., Ellison, A.M., Nguyen, A., Penick, C., DeMarco, B., Gotelli, N.J., Sanders, N.J., Dunn, R.R., Helms Cahan, S. 2019. Draft Aphaenogaster genomes expand our view of ant genome size variation across climate gradients. PeerJ 7, e6447 (doi:10.7717/PEERJ.6447).

- Liberti, J., B. Baer, and J. J. Boomsma. 2016. Queen reproductive tract secretions enhance sperm motility in ants. Biology Letters. 12:20160722. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0722

- Liberti, J., B. Baer, and J. J. Boomsma. 2018. Rival seminal fluid induces enhanced sperm motility in a polyandrous ant. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 18:12. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1144-y

- Liberti, J., Sapountzis, P., Hansen, L.H., Sørensen, S.J., Adams, R.M.M., Boomsma, J.J. 2015. Bacterial symbiont sharing in Megalomyrmex social parasites and their fungus-growing ant hosts. Molecular Ecology 24, 3151–3169 (doi:10.1111/MEC.13216).

- Liberti, J., Sapountzis, P., Hansen, L.H., Sørensen, S.J., Adams, R.M.M., Boomsma, J.J. 2015. Bacterial symbiont sharing in Megalomyrmex social parasites and their fungus-growing ant hosts. Molecular Ecology 24, 3151–3169 (doi:10.1111/MEC.13216).

- Lo, N., Beekman, M., Oldroyd, B.P. 2019. Caste in social insects: Genetic influences over caste determination. In: Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior (Second Edition), pp. 274–281 (doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20759-0).

- Mann, W. M. 1916. The Stanford Expedition to Brazil, 1911, John C. Branner, Director. The ants of Brazil. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 60: 399-490 (page 454, Combination in Acromyrmex)

- Mera‐Rodríguez, D., Fernández‐Marín, H., Rabeling, C. 2024. Phylogenomic approach to integrative taxonomy resolves a century‐old taxonomic puzzle and the evolutionary history of the Acromyrmex octospinosus species complex. Systematic Entomology, 1-26 (doi:10.1111/syen.12665).

- Meurgey, F. 2020. Challenging the Wallacean shortfall: A total assessment of insect diversity on Guadeloupe (French West Indies), a checklist and bibliography. Insecta Mundi 786: 1–183.

- Mokadam, C. 2021. Native and non-native ant impacts on native fungi (M.A. thesis, Buffalo State University).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Mueller, U.G., Ishak, H.D., Bruschi, S.M., Smith, C.C., Herman, J.J., Solomon, S.E., Mikheyev, A.S., Rabeling, C., Scott, J.J., Cooper, M., Rodrigues, A., Ortiz, A., Brandão, C.R.F., Lattke, J.E., Pagnocca, F.C., Rehner, S.A., Schultz, T.R., Vasconcelos, H.L., Adams, R.M.M., Bollazzi, M., Clark, R.M., Himler, A.G., LaPolla, J.S., Leal, I.R., Johnson, R.A., Roces, F., Sosa-Calvo, J., Wirth, R., Bacci, M. 2017. Biogeography of mutualistic fungi cultivated by leafcutter ants. Molecular Ecology 26, 6921–6937 (doi:10.1111/mec.14431).

- Nagel, M., Qiu, B., Brandenborg, L.E., Larsen, R.S., Ning, D., Boomsma, J.J., Zhang, G. 2020. The gene expression network regulating queen brain remodeling after insemination and its parallel use in ants with reproductive workers. Science Advances 6, eaaz5772 (doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz5772).

- Nehring, V., F. R. Dani, S. Turillazzi, J. J. Boomsma, and P. d'Ettorre. 2015. Integration strategies of a leaf-cutting ant social parasite. Animal Behaviour. 108:55-65. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.07.009

- Narváez-Vásquez, A., Gaviria, J., Vergara-Navarro, E.V., Rivera-Pedroza, L., Löhr, B. 2021. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) species diversity in secondary forest and three agricultural land uses of the Colombian Pacific Coast. Revista Chilena de Entomologia 47, 441–458 (doi:10.35249/rche.47.3.21.01).

- Nehring, V., Boomsma, J.J., d'Ettorre, P. 2012. Wingless virgin queens assume helper roles in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Current Biology 22, R671–R673 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.038).

- Palomeque, T., O. Sanllorente, X. Maside, J. Vela, P. Mora, M. I. Torres, G. Periquet, and P. Lorite. 2015. Evolutionary history of the Azteca-like mariner transposons and their host ants. Science of Nature. 102. doi:10.1007/s00114-015-1294-3

- Qiu, B., Larsen, R.S., Chang, N.-C., Wang, J., Boomsma, J.J., Zhang, G. 2018. Towards reconstructing the ancestral brain gene-network regulating caste differentiation in ants. Nature Ecology, Evolution 2, 1782–1791. (doi:10.1038/S41559-018-0689-X).

- Reich, G. C. 1793. Kurze Beschreibung neuen, oder noch wenig bekkanten Thiere, welche Herr Le Blond der naturforschenden Gesellschaft zu Paris aus Cayenne als Geschenk überschikt hat. Mag. Thierreichs 1: 128-134 (page 132, worker described)

- Ronque, M.U.V., Lyra, M.L., Migliorini, G.H., Bacci, M., Oliveira, P.S. 2020. Symbiotic bacterial communities in rainforest fungus-farming ants: evidence for species and colony specificity. Scientific Reports 10, 10172 (doi:10.1038/S41598-020-66772-6).

- Roux, J., Privman, E., Moretti, S., Daub, J.T., Robinson-Rechavi, M., Keller, L. 2014. Patterns of positive selection in seven ant genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31, 1661–1685 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msu141).

- Sales, T.A., Toledo, A.M.O., Lopes, J.F.S. 2020. The best of heavy queens: influence of post-flight weight on queens’ survival and productivity in Acromyrmex subterraneus (Forel, 1893) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux (doi:10.1007/S00040-020-00772-7).

- Sanne Nygaard, Guojie Zhang, Morten Schiøtt, Cai Li, Yannick Wurm, Haofu Hu, Jiajian Zhou, Lu Ji, Feng Qiu, Morten Rasmussen, Hailin Pan, Frank Hauser, Anders Krogh, Cornelis J.P. Grimmelikhuijzen, Jun Wang and Jacobus J. Boomsma (2011) The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming. Genome Research. 21:1339-1348. doi:10.1101/gr.121392.111

- Schultner, E., Pulliainen, U. 2020. Brood recognition and discrimination in ants. Insectes Sociaux 67, 11–34 (doi:10.1007/s00040-019-00747-3).

- Schultz, T.R., Bekkevold, D. ; Boomsma, J.J. 1998. Acromyrmex insinuator new species; an incipient social parasite of fungus-growing ants. Insectes Soc. 45(4): 457-471 (page 460, Raised to species)

- Siddiqui, J.A., Bamisile, B.S., Khan, M.M., Islam, W., Hafeez, M., Bodlah, I., Xu, Y. 2021. Impact of invasive ant species on native fauna across similar habitats under global environmental changes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28(39), 54362–54382 (doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15961-5).

- Travaglini, R.V., Forti, L.C., Arnosti, A., Stefanelli, L.E.P., Ferreira, A.R.F., Camargo, R.D.S., Camargo-Mathias, M.I. 2020. Description using ultramorphological techniques of the infection of Beauveria bassiana (Bals.-Criv.) Vuill. in larvae and adults of Atta sexdens (Linnaeus, 1758) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi - Ciências Naturais 15, 101–111 (doi:10.46357/bcnaturais.v15i1.201).

- Ulysséa, M.A., Brandão, C.R.F. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57, 217–224 (doi:10.1590/s0085-56262013005000002).

- Varela-Hernández, F., Medel-Zosayas, B., Martínez-Luque, E.O., Jones, R.W., De la Mora, A. 2020. Biodiversity in central Mexico: Assessment of ants in a convergent region. Southwestern Entomologist 454: 673-686.

- Wang, C., Billen, J., Wei, C., He, H. 2019. Morphology and ultrastructure of the infrabuccal pocket in Camponotus japonicus Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux 66, 637–646 (doi:10.1007/s00040-019-00726-8).

- Wheeler, G. C. 1949 [1948]. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689 (page 674, larva described)

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1986f. Supplementary studies on ant larvae: Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 94: 489-499 (page 496, larva described)

- Wheeler, W. M. 1937c. Mosaics and other anomalies among ants. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 95 pp. (page 70, senior synonym of pallida)

- Wiernasz, D.C., Hines, J., Parker, D.G., Cole, B.J. 2008. Mating for variety increases foraging activity in the harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Molecular Ecology 17, 1137–1144 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03646.x).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Adams B. J., S. A. Schnitzer, and S. P. Yanoviak. 2019. Connectivity explains local ant community structure in a Neotropical forest canopy: a large-scale experimental approach. Ecology 100(6): e02673.

- Ahuatzin D. A., E. J. Corro, A. Aguirre Jaimes, J. E. Valenzuela Gonzalez, R. Machado Feitosa, M. Cezar Ribeiro, J. Carlos Lopez Acosta, R. Coates, W. Dattilo. 2019. Forest cover drives leaf litter ant diversity in primary rainforest remnants within human-modified tropical landscapes. Biodiversity and Conservation 28(5): 1091-1107.

- Alayo D. P. 1974. Introduccion al estudio de los Himenopteros de Cuba. Superfamilia Formicoidea. Academia de Ciencias de Cuba. Instituto de Zoologia. Serie Biologica no.53: 58 pp. La Habana.

- Amat-G G., M. G. Andrade-C. and F. Fernández. (eds.) 1999. Insectos de Colombia. Volumen II. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 433 pp. 131975

- Bekkevold, D., J. Frydenberg and J.J. Boomsma. 1999. Multiple mating and facultative polygyny in the Panamanian leafcutter ant Acromyrmex echinatior. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 46:103-109.

- Boer P. 2019. Ants of Curacao, species list. Accessed on January 22 2019 at http://www.nlmieren.nl/websitepages/SPECIES%20LIST%20CURACAO.html

- Boomsma, J.J. , E.J. Fjerdingstad and J. Frydenberg. 1999. Multiple paternity, relatedness and genetic diversity in Acromyrmex leaf-cutter ants. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (B) 266:249-254.

- Bustos H., J. 1994. Contribucion al conocimiento de al fauna de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del occidente del Departamento de Narino (Colombia). Bol. Mus. Ent. Univ. Valle 2(1,2):19-30

- Castano-Meneses, G., M. Vasquez-Bolanos, J. L. Navarrete-Heredia, G. A. Quiroz-Rocha, and I. Alcala-Martinez. 2015. Avances de Formicidae de Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

- Celini L., V. Roy, J. Delabie, K. Questel, and P. Mora. 2012. Presence et origine d'Acromyrmex octospinosus (Reich, 1793) a Saint-Barthelemy, Petites Antilles (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Attini). Bulletin de la Societe Entomologique de France 117(2): 167-172.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- de Abreu J. M., and J. H. C. Delabie. 1986. Controle das formigas cortadeiras em plantios de cacau. Revista Theobroma 16(4): 199-211.

- Del Toro, I., M. Vázquez, W.P. Mackay, P. Rojas and R. Zapata-Mata. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Tabasco: explorando la diversidad de la mirmecofauna en las selvas tropicales de baja altitud. Dugesiana 16(1):1-14.

- Delabie J. H. C., R. Céréghino, S. Groc, A. Dejean, M. Gibernau, B. Corbara, and A. Dejean. 2009. Ants as biological indicators of Wayana Amerindian land use in French Guiana. Comptes Rendus Biologies 332(7): 673-684.

- Emery C. 1896. Formiche raccolte dal dott. E. Festa nei pressi del golfo di Darien. Bollettino dei Musei di Zoologia ed Anatomia Comparata della Reale Università di Torino 11(229): 1-4.

- Escalante Gutiérrez J. A. 1993. Especies de hormigas conocidas del Perú (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Revista Peruana de Entomología 34:1-13.

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fernández F., E. E. Palacio, W. P. Mackay, and E. S. MacKay. 1996. Introducción al estudio de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Colombia. Pp. 349-412 in: Andrade M. G., G. Amat García, and F. Fernández. (eds.) 1996. Insectos de Colombia. Estudios escogidos. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 541 pp

- Fernández F., V. Castro-Huertas, and F. Serna. 2015. Hormigas cortadoras de hojas de Colombia: Acromyrmex & Atta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Fauna de Colombia, Monografía No.5. Bogotá D.C., Colombia: Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 350 pp.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Fernandez-Marin, H., J.K. Zimmerman and W.T. Wzislo. 2007. Fungus garden platforms improve hygiene during nest establishment in Acromyrmex ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Attini). Insectes Sociaux 54:64-69

- Field Museum Collection, Chicago, Illinois (C. Moreau)

- Fontanla Rizo J.L. 1997. Lista preliminar de las hormigas de Cuba. Cocuyo 6: 18-21.

- Fontenla J. L. 2005. Species of ants (Formicidae) recorded during the rapid biological inventory of the Zapata Peninsula, 8-15 September 2002. In: Kirkconnell P., A., D. F. Stotz, y / and J. M. Shopland, eds. 2005. Cuba: Península de Zapata. Rapid Biological Inventories Report 07. The Field Museum, Chicago

- Fontenla J. L., and J. Alfonso-Simonetti. 2018. Classification of Cuban ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) into functional groups. Poeyana Revista Cubana de Zoologia 506: 21-30.

- Fontenla Rizo J. L. 1993. Composición y estructura de comunidades de hormigas en un sistema de formaciones vegetales costeras. Poeyana. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, Academia de Ciencias de Cuba 441: 1-19.

- Fontenla Rizo J. L. 1997. Lista preliminar de las hormigas de Cuba (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Cocuyo 6: 18-21.

- Forel A. 1905. Miscellanea myrmécologiques II (1905). Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 49: 155-185.

- Forel A. 1907. Formiciden aus dem Naturhistorischen Museum in Hamburg. II. Teil. Neueingänge seit 1900. Mitt. Naturhist. Mus. Hambg. 24: 1-20.

- Forel A. 1908. Catálogo systemático da collecção de formigas do Ceará. Boletim do Museu Rocha 1(1): 62-69.

- Forel A. 1908. Fourmis de Costa-Rica récoltées par M. Paul Biolley. Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles 44: 35-72.

- Forel A. 1912. Formicides néotropiques. Part II. 3me sous-famille Myrmicinae Lep. (Attini, Dacetii, Cryptocerini). Mémoires de la Société Entomologique de Belgique. 19: 179-209.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Galkowski C. 2016. New data on the ants from the Guadeloupe (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Bull. Soc. Linn. Bordeaux 151, 44(1): 25-36.

- Gonçalves C. R. 1961. O genero Acromyrmex no Brasil (Hym. Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 4: 113-180.

- Groc S., J. H. C. Delabie, F. Fernandez, M. Leponce, J. Orivel, R. Silvestre, Heraldo L. Vasconcelos, and A. Dejean. 2013. Leaf-litter ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a pristine Guianese rainforest: stable functional structure versus high species turnover. Myrmecological News 19: 43-51.

- Groc S., J. Orivel, A. Dejean, J. Martin, M. Etienne, B. Corbara, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2009. Baseline study of the leaf-litter ant fauna in a French Guianese forest. Insect Conservation and Diversity 2: 183-193.

- INBio Collection (via Gbif)

- Jacobs J. M., J. T. Longino, and F. J. Joyce. 2011. Ants of the Islas Murciélago: an inventory of the ants on tropical dry forest islands in northwest Costa Rica. Tropical Conservation Science 4(2): 149-171.

- Jaffe, Klaus and Lattke, John. 1994. Ant Fauna of the French and Venezuelan Islands in the Caribbean in Exotic Ants, editor D.F. Williams. 182-190.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kooij P. W., B. M. Dentinger, D. A. Donoso, J. Z. Shik, and E. Gaya. 2018. Cryptic diversity in Colombian edible leaf-cutting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insects 9: 191.

- Kusnezov N. 1963. Zoogeografia de las hormigas en sudamerica. Acta Zoologica Lilloana 19: 25-186

- Landero-Torres I., M. A. Garcia-Martinez, M. E. Galindo-Tovar, O. R. Leyva-Ovalle, H. E. Lee-Espinosa, J. Murguia-Gonzalez, and J. Negrin-Ruiz. 2014. Alpha diversity of the myrmecofauna of the Natural Protected Area Metlac from Fortin, Veracruz, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist 39(3): 541-553.

- Levings S. C. 1983. Seasonal, annual, and among-site variation in the ground ant community of a deciduous tropical forest: some causes of patchy species distributions. Ecological Monographs 53(4): 435-455.

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/

- Longino J. T. 2013. Ants of Honduras. Consulted on 18 Jan 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/longinollama/reports/ants-of-honduras

- Longino J. T. 2013. Ants of Nicargua. Consulted on 18 Jan 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/longinollama/reports/ants-of-nicaragua

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Longino J. T., J. Coddington, and R. K. Colwell. 2002. The ant fauna of a tropical rain forest: estimating species richness three different ways. Ecology 83: 689-702.

- Maes, J.-M. and W.P. MacKay. 1993. Catalogo de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia 23.

- Marques Silva T. G. 2013. Partición aditiva de la diversidad de hormigas entre escalas espaciales en el Bosque Tropical Caducifolio de México. In Formicidae de Mexico (eds. M. Vasquez-Bolanos, G. Castano-Meneses, A. Cisneros-Caballero, G. A. Quiroz-Rocha, and J. L. Navarrete-Heredia) p 83-89.

- Medina U. C. A., F. Fernandez, and M. G. Andrade-C. 2010. Insectos: escarabajos coprofagos, hormigas y mariposas. Capitulo 6. Pp 197-215. En: Lasso, C. A., J. S. Usma, F. Trujillo y A. Rial (eds.). 2010. Biodiversidad de la cuenca del Orinoco: bases científicas para la identificación de áreas prioritarias para la conservación y uso sostenible de la biodiversidad. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, WWF Colombia, Fundación Omacha, Fundación La Salle e Instituto de Estudios de la Orinoquia (Universidad Nacional de Colombia). Bogotá, D. C., Colombia.

- Pérez-Sánchez A. J., J. E. Lattke, and M. A. Riera-Valera. 2014. The Myrmecofauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Macanao Semi-arid Peninsula in Venezuela: An Altitudinal Variation Glance. J Biodivers Biopros Dev 1: 116. doi:10.4172/ijbbd.1000116

- Philpott, S.M., P. Bichier, R. Rice, and R. Greenberg. 2007. Field testing ecological and economic benefits of coffee certification programs. Conservation Biology 21: 975-985.

- Poulsen, M., A.N.M. Bot, M.G. Neilsen and J.J. Boomsma. 2002. Experimental Evidence for the Costs and Hygienic Significance of the Antibiotic Metapleural Gland Secretion in Leaf-Cutting Ants. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 52 (2):151-157

- Poulsen, M., W.O.H. Hughes and J.J. Boomsma. 2006. Differential resistance and the importance of antibiotic production in Acromyrmex echinatior leaf-cutting ant castes towards the entomopathogenic fungus Aspergillus nomius. Insectes Sociaux 53:349-355

- Reddell J. R., and J. C. Cokendolpher. 2001. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from caves of Belize, Mexico, and California and Texas (U.S.A.) Texas. Texas Memorial Museum Speleological Monographs 5: 129-154.

- Reynoso-Campos J. J., J. A. Rodriguez-Garza, and M. Vasquez-Bolanos. 2015. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Isla Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico (pp. 27-39). En: Castaño Meneses G., M. Vásquez-Bolaños, J. L. Navarrete-Heredia, G. A. Quiroz-Rocha e I. Alcalá-Martínez (Coords.). Avances de Formicidae de México. UNAM, Universiad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Jalisco.

- Santschi F. 1925. Revision du genre Acromyrmex Mayr. Revue Suisse de Zoologie 31: 355-398.

- Schultz T. R., D. Bekkevold, J. J. Boomsma. 1998. Acromyrmex insinuator new species; an incipient social parasite of fungus-growing ants. Insectes Soc. 45(4): 457-471.

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.

- Sumner, S., D.K. Aanen, J. Delabie and J.J. Boomsma. 2004. The evolution of social parasitism inAcromyrmexleaf-cutting ants: a test of Emerys rule. Insectes Sociaux 51(1):37-42.

- Sumner, S., W.O.H. Hughes and J.J. Boomsma. 2003. Evidence for Differential Selection and Potential Adaptive Evolution in the Worker Caste of an Inquiline Social Parasite. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 54(3):256-263

- Ulyssea M. A., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57(2): 217224.

- Ulysséa M. A., C. R. F. Brandão. 2013. Ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) from the seasonally dry tropical forest of northeastern Brazil: a compilation from field surveys in Bahia and literature records. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 57(2): 217-224.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Weber N. A. 1938. The food of the giant toad, Bufo marinus (L.), in Trinidad and British Guiana with special reference to the ants. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 31: 499-503.

- Weber N. A. 1941. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VII. The Barro Colorado Island, Canal Zone, species. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 12: 93-130.

- Weber N. A. 1945. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VIII. The Trinidad, B. W. I., species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 16: 1-88.

- Weber N. A. 1946. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part IX. The British Guiana species. Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 17: 114-172.

- Weber N. A. 1947. Lower Orinoco River fungus-growing ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae, Attini). Boletín de Entomologia Venezolana 6: 143-161.

- Weber, Neal A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79:141-145.

- Weber, Neil A. 1968. Tobago Island Fungus-growing Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 79(6):141-145.

- Wetterer J. K. 1993. Foraging and nesting ecology of a Costa Rican leaf-cutting ant, Acromyrmex volcanus. Psyche (Camb.) 100: 65-76.

- Wetterer J. K. 1998. Ants on Cecropia trees in urban San José, Costa Rica. Florida Entomologist 81: 118-121.

- Wheeler G. C. 1949. The larvae of the fungus-growing ants. Am. Midl. Nat. 40: 664-689.

- Wheeler W. M. 1905. The ants of the Bahamas, with a list of the known West Indian species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21: 79-135.

- Wheeler W. M. 1913. The ants of Cuba. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 54: 477-505.

- Wheeler W. M. 1919. The ants of Tobago Island. Psyche (Cambridge) 26: 113.

- Wheeler W. M. 1922. The ants of Trinidad. American Museum Novitates 45: 1-16.

- Wheeler W. M. 1937. Mosaics and other anomalies among ants. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 95 pp.

- Wheeler, William Morton. 1916. Ants Collected in Trinidad by Professor Roland Thaxter, Mr. F. W. Urich, and Others. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparitive Zoology at Harvard University. 40(8):322-330

- Zelikova, T.J. and M.D. Breed. 2008. Effects of habitat disturbance on ant community composition and seed dispersal by ants in a tropical dry forest in Costa Rica. Journal of Tropical Ecology 24:309-316

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Highly invasive

- Need species key

- Tropical

- Ant Associate

- Host of Acromyrmex insinuator

- Fungus Associate

- Host of Aspergillus flavus

- Host of Ophiocordyceps kniphofioides

- Nematode Associate

- Host of Steinerema carpocapsae

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Attini

- Acromyrmex

- Acromyrmex octospinosus

- Myrmicinae species

- Attini species

- Acromyrmex species