Lasius claviger

| Lasius claviger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Lasiini |

| Genus: | Lasius |

| Section: | flavus clade |

| Species group: | claviger |

| Species: | L. claviger |

| Binomial name | |

| Lasius claviger (Roger, 1862) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Smaller Yellow Ant | |

| Language: | English |

This subterranean ant nests in soil under stones and in well-decayed tree stumps in young to mature forests (Ellison et al., 2012). It exhibits temporary social parasitism. Queens found new colonies by infiltrating an established nest of another Lasius species, including Lasius alienus (de la Mora et al., 2021; Raczkowski & Luque, 2011), Lasius americanus and Lasius neoniger (and an unknown species, see Janda et al., 2004), killing the queen and using host workers to care for her initial brood. It is also a host for the temporary parasite Lasius plumopilosus. Workers are generalist predators and also feed on honeydew secreted by root-feeding mealy-bugs. Colonies can be enormous and spread over wide areas in the forest. Mating flights occur very late in the season, often in late September or early October. The queens mate and then spend the winter under rocks or wood, emerging in the spring to seek nests of their hosts. (Ellison et al., 2012)

| At a Glance | • Temporary parasite |

Photo Gallery

Identification

Keys including this Species

- Key to Lasius-Nearctic workers of Acanthomyops short key

- Key to Lasius-Nearctic Acanthomyops workers

- Key to Lasius-Nearctic Acanthomyops queens

- Key to Lasius-Nearctic Acanthomyops males

- Key to North American Lasius Species

- Key to New England Lasius

Distribution

Southern New England to Minnesota, south to Kansas and east to Florida.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 50.938° to 30.55856°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

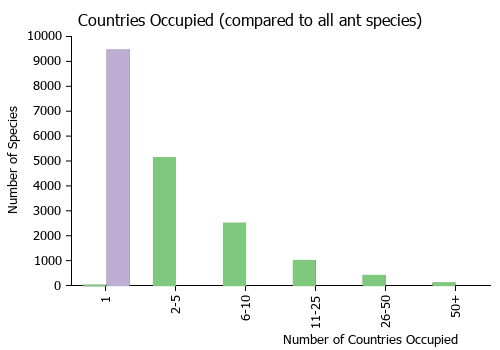

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

This section is reported, slightly modified, from Wing (1968).

Habitat data in varying degrees of completeness were associated with 137 of the 486 samples of claviger. Samples collected in woods numbered 78, those in the open, 30, those of uncertain origin, 29. With respect to immediate nest-cover, 45 were under stones, 21 associated with logs and stumps, 1 came from a grassy mound, 30 with miscellaneous or no cover, and 40 of uncertain status. One of the 30 nests in the miscellaneous category was under a beef marrow bone in a backyard in Ithaca, New York.

In addition to the data associated with specimens received for study; Carter (1962b) and Talbot (1963) have published data based on a large number of colonies. Carter found claviger common throughout North Carolina except in the Coastal Plain. Nests were located under stones, in well-decayed stumps, and without cover in a variety of soil types ranging from red clay to loose sand. They occurred in fields of various ages and in forests ranging from young to mature. The forests were composed of various species of pines, oaks, and hickory. Talbot, working in southern Michigan, found claviger versatile in its nesting habits. Nests were about equally frequent in deep woods, open woods, and fields. In deep woods, most nests were associated with logs and stumps. In open woods, stones and old logs usually formed the immediate nest-cover. Nests located in the open often were not associated with stones or wood; small mounds frequently marked their location. The soil thrown up at the time of flight probably was overgrown with grass, eventually becoming permanent mounds. Some of them were up to 3 feet in diameter and 2 to 4 inches high. My own field observations on claviger, principally in Minnesota, New York, and North Carolina, indicate that the location and immediate cover of nests varies somewhat from one local to another. Before more precise quantitative statements than those indicated above can be made, a number of habitats in various parts of the range need to be uniformly investigated.

Reproduction

Annual sexual cycle June may be taken as a starting point for the cycle of this species. During June and July most records of sexual forms in nests are based on queen larvae and pupae. The immature stages of queens were investigated in claviger to determine their seasonal distribution as closely as possible. It is estimated that 6 weeks to 2 months elapse from the first appearance of queen larvae to the time when adult queens are found in the nest. The timing for males is probably similar to that of females. Investigation of the seasonal distribution of the sexual immatures of other taxa was done far less exhaustively than in claviger. It is likely, however, that the estimate for claviger will hold for other taxa producing alates during the warmer months of the year.

By August, mature claviger nests contain adult alates in sizable numbers. These nests remain relatively numerous on into October. Most nuptial flights begin in September and continue into November, with a few occurring earlier and later.

Associated with flights is the appearance of many dealate queens. In claviger, unlike other species, the dealate queens remain numerous until the end of the following April, when they suddenly disappear. claviger infests buildings infrequently, so most of these queens are collected out-of-doors, either singly or in groups. Occasionally they are associated with alate females, and more rarely with males. They are found in woods or fields under trash, stones, logs, or other cover. It is evident that large numbers of dealate queens of claviger regularly overwinter in all or most parts of the range. The reasons for their sudden disappearance in late April are unknown. Intensive field studies of this species during the spring months might well lead to an understanding of its method of colony foundation. At worst such field studies stand a chance of turning up clues that could help in designing experiments to test likely alternatives.

claviger is one of the two species with a sexual cycle that spans most of the year. The chief reason for this extensive time-range is the continuing abundance of overwintering dealate queens, which occur long after normal flight activities are over.

Talbot (1963) reported that extreme claviger flight dates at Tiffin, Ohio were September 11 and 25 during the period from 1933 to 1944. Buren (1944) reported flights during late August, September, and October in Iowa. Groskin (1947) reported an unusually late flight of claviger on December 3, 1963 in Pennsylvania. Talbot's observations at the Edwin S. George Reserve in Livingston Co., Michigan began in early June and ended in early September each year. The first date on which she found a claviger nest with adult alates was August 20. In commenting on her flight observations in Ohio, she stated that rains induced the workers to open the nests. Flights took place in mid-afternoon, and were favored by decreasing light, warmth, and high humidity. The nest observed during the flight of September 22 still contained males and females on October 21. Because of this observation, she surmised that the alates may have overwintered in the nest and flown during the next spring. Since flights are known to occur later than October 21, it does not necessarily follow that this colony failed to empty its nest of alates during that year. Even when a few alates do overwinter in parental nests, there is no reason to assume that this results in flights during the following spring. To my knowledge no spring flights have been observed for claviger.

Flight Period

| X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the ant Lasius interjectus (a temporary parasite) (de la Mora et al., 2021; Raczkowski & Luque, 2011).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Forda marginata (a trophobiont) (Cockerell, 1903; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a host for the nematode Oscheius dolichura (a parasite) (Quevillon, 2018) (multiple encounter modes; indirect transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a host for the nematode Oscheius dolichura (a parasite) (Nickle & Ayre, 1966).

Nest Guests

In addition to the 2 or 3 dozen vials with aphids and coccids, and a few with mites, the following papers listed other insects associated with claviger: Evans (1961), Pseudisobrachium ashmeadi and P. elongatum (Hymenoptera: Bethylidae). Schwarz (1890), Batrisodes montrosus, B. ferox (Coleoptera: Pselaphidae), Panagaeus crucigerus (Coleoptera: Carabidae), Quedius molochinus, Homoeusa expansa (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae), and the larvae of Brachyacantha ursina (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), which were preying on the Pemphigus pastured by the ants. Wickham (1898), Batrisodes frontalis found in the galleries of a nest under a log. Park (1935), Batrisodes globosus. Park (1932) studied the myrmecocole, Batrisodes globosus in a Lasius americanus colony. He concluded that this species may act occasionally as a predator of living host larvae, but more frequently aids the host colony by disposing of dead larvae. The habits of B. globosus are probably similar in the colonies of the closely related L.claviger.

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103541. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103542. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0103543. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- claviger. Formica clavigera Roger, 1862a: 241, pl. 1, fig. 13 (q.) U.S.A. Mayr, 1870b: 950 (w.m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J., 1953c: 155 (l.). Combination in Acanthomyops: Mayr, 1862: 700; in Lasius: Mayr, 1870b: 950; in Lasius (Acanthomyops): Emery, 1893i: 642; in Acanthomyops: Donisthorpe, 1916c: 276; in Lasius: Ward, 2005: 13. Senior synonym of parvula: Wing, 1968: 67. See also: Creighton, 1950a: 429; Regnier & Wilson, 1968: 955; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1440.

- parvula. Lasius (Acanthomyops) parvula Smith, M.R. 1934b: 213 (w.) U.S.A. Combination in Acanthomyops: Creighton, 1950a: 432; in Lasius: Ward, 2005: 13. Junior synonym of claviger: Wing, 1968: 67.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Wing (1968) - Body size and pilosity moderate, pubescence dilute to moderate. Crest of petiolar scale sharp to moderate, usually distinctly to feebly emarginate. Separated from Lasius interjectus by the more or less uniform distribution of standing hairs over dorsum of gaster and by lower SL. Separated from Lasius latipes by the conformation of the petiolar scale, and standing hairs usually confined to posterior 2h of gula. Separated from Lasius californicus by SI usually 80 or less. Separation from Lasius coloradensis is difficult as discussed in the treatment of variation of that taxon.

Standing body hairs simple to barbulate, moderate to numerous, of variable length, but most not extremely short. In most specimens, standing femoral hairs are largely confined to the fore femora. Pubescence variable, moderate at base of gaster, more dilute on its dorsum; that on front of head very dilute to moderate, but rarely more dense than at base of gaster. Body surface usually at least feebly shining. Body varying in appearance from robust to slender, the smaller specimens usually appearing at least fairly slender. Body and appendages pale yellow to brown.

Queen

Wing (1968) - Head not deformed. Antennal scapes and funiculi weakly clavate to clavate, antepenultimate segment of funiculus not over 1.55 times wider than long. SI not over 66, usually 63 or less. Body size moderate; HW at least 1.22, and usually 1.38 mm or more; AL ranging from 2.08 to 2.82 mm, usually over 2.25 mm. FW 0.33 to 0.51 mm; fore femora without genual plates; FI 33 to 42. Crest of petiolar scale sharp to moderately sharp, usually distinctly emarginate. Scale covered with 45 or fewer standing hairs. Gula with standing hairs usually confined to its posterior 2/3, and usually numbering less than 24, their maximum length rarely over 0.30 mm. Pilosity on dorsum of gaster: (1) confined to rows on posterior edges of tergites beyond first, or (2) more or less evenly distributed over entire surface, or (3) exhibiting a pattern intermediate between these two. Pubescence on head and gaster usually dilute, occasionally moderate, usually more dilute on head than on gaster. Body color medium to dark brown, not appearing black to naked eye.

Standing body hairs simple to finely barbulate. Most standing femoral hairs on fore femora. Most of body surface shining, often strongly so. Appendages usually lighter in color than body.

Male

Wing (1968) - Scapes slender to somewhat clavate. AL usually 1.60 mm or more, HW often 1.00 mm or more, SL usually 0.65 mm or more. Terminal width of pygostyle 0.04 mm or more. Width of petiolar scale through spiracles at least 1.5 times its height above spiracles. Pubescence dilute to moderate. Body color brown to moderately dark brown, but rarely dark enough to appear black or nearly black to naked eye.

Standing body hairs simple to minutely barbulate, usually moderate in number. Body surface usually shining. Color medium reddish brown to dark brown, head and alitrunk often darker than gaster, appendages lighter.

Hybrids

Wing (1968) described a hybrid form of this species.

Lasius latipes × claviger hybrid

This sporadic form is recorded in a band from Minnesota and Central Illinois east to New England and New Jersey. It is by far the most common of all known hybrid taxa, most of which are known from only one or two collections.

Worker

Intermediate between latipes and claviger, but having the general appearance of latipes, from which it is not now reliably separable.

Pubescence on gaster dilute to dense. Petiolar scale variable, but usually quite similar to that of latipes. Standing hairs on gula almost invariably cover the entire surface. Length of standing body hairs and body size average and range a little greater than in latipes. Body color yellow to brownish yellow.

Queen

Intermediate between latipes and claviger. Head not or only slightly deformed. Antennal scapes and funiculi decidedly clavate; antepenultimate segment of funiculus greater than 1.55 and less than 2.30 times wider than long. Entire surface of gula covered with from 24 to 40 standing hairs, with maximum length usually less than 0.30 mm. FW 0.50 to 0.75 mm, usually at least 0.55 mm; genual plates of fore femora moderate, not conspicuous. FI 43-54. Crest of petiolar scale usually blunt to very blunt, not emarginate, rarely sharper and feebly emarginate. Scale covered with 50-75 standing hairs. Most standing femoral hairs confined to fore femora.

Pubescence on gaster from very dilute to very dense, that on rest of body usually much less dense, most of body usually shining. Pilosity on gaster variable, but most specimens have standing hairs largely confined to the posterior edges of tergites beyond first. Body color variable, most frequently a medium-dark castaneous brown. Some specimens are lighter yellowish brown, others are a dark grayish brown.

Male

Typical of the males of latipes in all known respects.

Type Material

Wing (1968) - Type locality: Pennsylvania. Location of type: The type specimen, a queen bearing the locality data "Pennsylvanien", is in the collection of the Institut fur spezielle Zoologie und Zoologisches Museum der Humboldt-Universitat, Berlin. The type, probably collected by Schaum near Philadelphia, is more or less intermediate between the "typical" and "variant" forms. The distribution of standing hairs on the dorsum of the gaster is that of the "typical" form. The antennal scapes and funiculi are weakly clavate, as in the "variant" form. Most of the standardized measurements fall in the midrange of the "variant" form. The 2 other queens mailed to me for examination bear "Nordamerika" labels. They appear to represent samples from separate localities, both of which are probably different from that of the type.

References

- Boudinot, B.E., Borowiec, M.L., Prebus, M.M. 2022. Phylogeny, evolution, and classification of the ant genus Lasius, the tribe Lasiini and the subfamily Formicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Systematic Entomology 47, 113-151 (doi:10.1111/syen.12522).

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Cantone S. 2017. Winged Ants, The Male, Dichotomous key to genera of winged male ants in the World, Behavioral ecology of mating flight (self-published).

- Carroll, T.M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). M.S. thesis, Purdue University.

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 429, see also)

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- de la Mora, A., Sankovitz, M., Purcell, J. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies. Myrmecological News 30: 53-71 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:053).

- Donisthorpe, H. 1916e. Synonymy of some genera of ants. [concl.]. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 28: 275-277 (page 276, Combination in Acanthomyops)

- Ellison, A.M., Gotelli, N.J., Farnsworht, E.J., Alpert, G.D. 2012. A Field Guide to the Ants of New England. Yale University Press, 256 pp.

- Emery, C. 1893k. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Geogr. Biol. Tiere 7: 633-682 (page 642, Combination in Lasius (Acanthomyops))

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87 (doi:10.3897@jhr.70.35207).

- Janda, M., Folkova, D. & Zrzavy, J. 2004. Phylogeny of Lasius ants based on mitochondrial DNA and morphology, and the evolution of social parasitism in the Lasiini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33: 595‐614.

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Mayr, G. 1862. Myrmecologische Studien. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 12: 649-776 (page 700, Combination in Acanthomyops)

- Mayr, G. 1870b. Neue Formiciden. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 20: 939-996 (page 950, Combination in Lasius)

- Mayr, G. 1870b. Neue Formiciden. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 20: 939-996 (page 950, worker, male described)

- Meurville, M.-P., LeBoeuf, A.C. 2021. Trophallaxis: the functions and evolution of social fluid exchange in ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 31: 1-30 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:001).

- Nickle, W.R., Ayre, G.L. 1966. Caenorhabditis dolichura (A. Schneider, 1866) Dougherty (Rhabditidae, Nematoda) in the head glands of the ants Camponotus herculeanus (L.) and Acanthomyops claviger (Roger) in Ontario. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Ontario 96: 96–98.

- Regnier, F. E.; Wilson, E. O. 1968. The alarm-defense system of the ant Acanthomyops claviger. J. Insect Physiol. 14: 955-970 (page 955, see also)

- Rericha, L. 2007. Ants of Indiana. Indiana Department of Natural Resources, 51pp.

- Roger, J. 1862a. Einige neue exotische Ameisen-Gattungen und Arten. Berl. Entomol. Z. 6: 233-254 (page 241, pl. 1, fig. 13 queen described)

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. i-xvi, 1199-2209. (page 1440, see also)

- Ward, P.S. 2005. A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 936: 1-68 (page 13, revived combination in Lasius (Acanthomyops))

- Waters, J.S., Keough, N.W., Burt, J., Eckel, J.D., Hutchinson, T., Ewanchuk, J., Rock, M., Markert, J.A., Axen, H.J., Gregg, D. 2022. Survey of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in the city of Providence (Rhode Island, United States) and a new northern-most record for Brachyponera chinensis (Emery, 1895). Check List 18(6), 1347–1368 (doi:10.15560/18.6.1347).

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1953c. The ant larvae of the subfamily Formicinae. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 46: 126-171 (page 155, larva described)

- Wing, M. W. 1968a. Taxonomic revision of the Nearctic genus Acanthomyops (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Mem. Cornell Univ. Agric. Exp. Stn. 405: 1-173 (page 67, Senior synonym of parvula)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Bare O. S. 1929. A taxonomic study of Nebraska ants, or Formicidae (Hymenoptera). Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA.

- Beck D. E., D. M. Allred, W. J. Despain. 1967. Predaceous-scavenger ants in Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 27: 67-78

- Belcher A. K., M. R. Berenbaum, and A. V. Suarez. 2016. Urbana House Ants 2.0.: revisiting M. R. Smith's 1926 survey of house-infesting ants in central Illinois after 87 years. American Entomologist 62(3): 182-193.

- Blades, D.C.A. and S.A. Marshall. Terrestrial arthropods of Canadian Peatlands: Synopsis of pan trap collections at four southern Ontario peatlands. Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 169:221-284

- Canadensys Database. Dowloaded on 5th February 2014 at http://www.canadensys.net/

- Carroll T. M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Master's Thesis Purdue university, 385 pages.

- Cheesman L. E., and W. C. Crawley. 1928. A contribution towards the insect fauna of French Oceania. - Part III. Formicidae. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 10(2): 514-525.

- Chessman, L. E. and Crawley, W. C. 1928. A Contribution towards the Insect Fauna of French Oceania. Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 2(10):514-525.

- Clark Adam. Personal communication on November 25th 2013.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Coovert G. A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ohio Biological Survey, Inc. 15(2): 1-207.

- Coovert, G.A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin New Series Volume 15(2):1-196

- Davis W. T., and J. Bequaert. 1922. An annoted list of the ants of Staten Island and Long Island, N. Y. Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 17(1): 1-25.

- Del Toro I., K. Towle, D. N. Morrison, and S. L. Pelini. 2013. Community Structure, Ecological and Behavioral Traits of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Massachusetts Open and Forested Habitats. Northeastern Naturalist 20: 1-12.

- Del Toro, I. 2010. PERSONAL COMMUNICATION. MUSEUM RECORDS COLLATED BY ISRAEL DEL TORO

- Dennis C. A. 1938. The distribution of ant species in Tennessee with reference to ecological factors. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 31: 267-308.

- Deyrup M. 2016. Ants of Florida: identification and natural history. CRC Press, 423 pages.

- Deyrup, M. 2003. An updated list of Florida ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 86(1):43-48.

- Drummond F. A., A. M. llison, E. Groden, and G. D. Ouellette. 2012. The ants (Formicidae). In Biodiversity of the Schoodic Peninsula: Results of the Insect and Arachnid Bioblitzes at the Schoodic District of Acadia National Park, Maine. Maine Agricultural and forest experiment station, The University of Maine, Technical Bulletin 206. 217 pages

- DuBois M. B. 1981. New records of ants in Kansas, III. State Biological Survey of Kansas. Technical Publications 10: 32-44

- Dubois, M.B. and W.E. Laberge. 1988. An Annotated list of the ants of Illionois. pages 133-156 in Advances in Myrmecology, J. Trager

- Ellison A. M., S. Record, A. Arguello, and N. J. Gotelli. 2007. Rapid Inventory of the Ant Assemblage in a Temperate Hardwood Forest: Species Composition and Assessment of Sampling Methods. Environ. Entomol. 36(4): 766-775.

- Ellison A. M., and E. J. Farnsworth. 2014. Targeted sampling increases knowledge and improves estimates of ant species richness in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 21(1): NENHC-13NENHC-24.

- Emery C. 1893. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 7: 633-682.

- Field Museum Collection, Chicago, Illinois (C. Moreau)

- Frye J. A., T. Frye, and T. W. Suman. 2014. The ant fauna of inland sand dune communities in Worcester County, Maryland. Northeastern Naturalist, 21(3): 446-471.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Guénard B., K. A. Mccaffrey, A. Lucky, and R. R. Dunn. 2012. Ants of North Carolina: an updated list (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 3552: 1-36.

- Hayes W. P. 1925. A preliminary list of the ants of Kansas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). [concl.]. Entomological News 36: 69-73

- Headley A. E. 1943. The ants of Ashtabula County, Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). The Ohio Journal of Science 43(1): 22-31.

- Hill, J.G. 2006. Ants collected at Okatibbee Lake, Lauderdale County, Mississippi

- Ivanov, K. 2019. The ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): an updated checklist. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 70: 65–87.

- Ivanov K., L. Hightower, S. T. Dash, and J. B. Keiper. 2019. 150 years in the making: first comprehensive list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Virginia, USA. Zootaxa 4554 (2): 532–560.

- Kjar D. 2009. The ant community of a riparian forest in the Dyke Marsh Preserve, Fairfax County, Virginiam and a checklist of Mid-Atlantic Formicidae. Banisteria 33: 3-17.

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Lubertazi, D. Personal Communication. Specimen Data from Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard

- Lynch J. F. 1988. An annotated checklist and key to the species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Chesapeake Bay region. The Maryland Naturalist 31: 61-106

- MacGown, J.A. and JV.G. Hill. Ants of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Tennessee and North Carolina).

- Menke S. B., E. Gaulke, A. Hamel, and N. Vachter. 2015. The effects of restoration age and prescribed burns on grassland ant community structure. Environmental Entomology http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv110

- Menke S. B., and N. Vachter. 2014. A comparison of the effectiveness of pitfall traps and winkler litter samples for characterization of terrestrial ant (Formicidae) communities in temperate savannas. The Great Lakes Entomologist 47(3-4): 149-165.

- Merle W. W. 1939. An Annotated List of the Ants of Maine (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News. 50: 161-165

- Munsee, J. R.; Jansma, W. B.; Schrock, J. R. 1986. Revision of the checklist of Indiana ants with the addition of five new species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1985, publ. 1986 Vol. 95 pp. 265-274

- Nuhn, T.P. and C.G. Wright. 1979. An Ecological Survey of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Landscaped Suburban Habitat. American Midland Naturalist 102(2):353-362

- Ouellette G. D., F. A. Drummond, B. Choate and E. Groden. 2010. Ant diversity and distribution in Acadia National Park, Maine. Environmental Entomology 39: 1447-1556

- Procter W. 1938. Biological survey of the Mount Desert Region. Part VI. The insect fauna. Philadelphia: Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, 496 pp.

- Raczkowski, J.M. and G.M. Luque. 2011. Colony founding and social parasitism in Lasius (Acanthomyops). Insectes Sociaux 58:237-244

- Rees D. M., and A. W. Grundmann. 1940. A preliminary list of the ants of Utah. Bulletin of the University of Utah, 31(5): 1-12.

- Smith M. R. 1931. An additional annotated list of the ants of Mississippi (Hym.: Formicoidea). Entomological News 42: 16-24.

- Smith M. R. 1935. A list of the ants of Oklahoma (Hymen.: Formicidae) (continued from page 241). Entomological News 46: 261-264.

- Smith M. R. 1952. On the collection of ants made by Titus Ulke in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the early nineties. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 60: 55-63.

- Smith M. R. 1962. A new species of exotic Ponera from North Carolina (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Acta Hymenopterologica 1: 377-382.

- Smith M. R. 1965. House-infesting ants of the eastern United States. Their recognition, biology, and economic importance. United States Department of Agriculture. Technical Bulletin 1326: 1-105.

- Sturtevant A. H. 1931. Ants collected on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Psyche (Cambridge) 38: 73-79

- Talbot M. 1976. A list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Edwin S. George Reserve, Livingston County, Michigan. Great Lakes Entomologist 8: 245-246.

- Warren, L.O. and E.P. Rouse. 1969. The Ants of Arkansas. Bulletin of the Agricultural Experiment Station 742:1-67

- Wheeler G. C., J. N. Wheeler, and P. B. Kannowski. 1994. Checklist of the ants of Michigan (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Great Lakes Entomologist 26(4): 297-310

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler J. 1989. A checklist of the ants of Oklahoma. Prairie Naturalist 21: 203-210.

- Wheeler W. M. 1905. An annotated list of the ants of New Jersey. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 21: 371-403.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. Fauna of New England. 7. List of the Formicidae. Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 1-24

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. Fauna of New England. 7. List of the Formicidae. Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 1-24.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. A list of Indiana ants. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 26: 460-466.

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler and P.B. Kannowski. 1994. CHECKLIST OF THE ANTS OF MICHIGAN (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE). Great Lakes Entomologist 26:1:297-310

- Wheeler, William Morton. 1932. Ants from the Society Islands. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin. 113:13-19.

- Wing M. W. 1939. An annotated list of the ants of Maine (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomological News 50:161-165.

- Wing M. W. 1968. Taxonomic revision of the Nearctic genus Acanthomyops (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Memoirs of the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station 405: 1-173.

- Young J., and D. E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publication. Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station 71: 1-42.

- Young, J. and D.E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publications of Oklahoma State University MP-71

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- Ant Associate

- Host of Lasius alienus

- Host of Lasius americanus

- Host of Lasius neoniger

- Host of Lasius plumopilosus

- Temporary parasite

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- FlightMonth

- Host of Lasius interjectus

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Forda marginata

- Host of Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae

- Nematode Associate

- Host of Oscheius dolichura

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Formicinae

- Lasiini

- Lasius

- Lasius claviger

- Formicinae species

- Lasiini species

- Lasius species

- Need Overview

- Need Body Text