Formica obscuripes

| Formica obscuripes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Formicini |

| Genus: | Formica |

| Species group: | rufa |

| Species: | F. obscuripes |

| Binomial name | |

| Formica obscuripes Forel, 1886 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Western Thatching Ant | |

| Language: | English |

Known as the Western Thatching Ant, Formica obscuripes is a dominant component in many habitats across much of western North America. Their large thatched mounds and huge colonies with tens or hundreds of thousands of workers are distinctive and when encountered there is little doubt as to their identity. When at high density they seem to suppress other Formica diversity in the vicinity of their nests. Workers are variable in size (polymorphic), forage during the day in large numbers across the ground and on vegetation, and perform nest maintainance on their mounds and in the immediate vicinity. They are host to a handful of other ants (inquilines and parasites, including Formicoxenus hirticornis and Formica talbotae) and a large number of guest insects (myrmecophiles and opportunists).

| At a Glance | • Polygynous • Temporary parasite |

Photo Gallery

Identification

Keys including this Species

Distribution

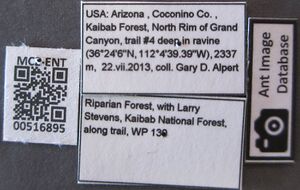

This taxon is especially prevalent in the Pacific Northwest and is uncommon in New Mexico. A collection of Formica obscuripes was made at Ft. Davis, Texas, in 1902 (specimen in AMNH) but it has not been collected since and it is unlikely to occur in this area.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 54.39017404° to 33.2938°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

Habitat

Formica obscuripes inhabits a wide range of habitats, including grasslands, prairies, sagebrush, shrub-steppe, mixed deciduous forest up to pinyon-juniper, coniferous forests, ponderosa pine-riparian areas, coastal and inland dunes, and alpine meadows. Nests are often found along the edges of meadows and other open areas.

Nesting Habits

This species builds large mounds consisting of small pieces of plant material with tunnels and galleries extending into the soil below the mound. It is one of the only true thatching ants, with mounds constructed completely of vegetative debris (soil is used in most "thatching" ants). New colonies are typically established in an open areas devoid of cover, under a small piece of rotten wood or small stump, with this wood remaining at the base of the nest as the nest grows over time. The mound is built using various material, commonly short twigs, grass stems, conifer needles, and other material, with specific composition based on available plant material from the area around the nest. The materials used can change over time as the surrounding vegetation changes. The size of mounds is highly variable and depends on the age and health of the colony. In their early stages nests are under logs or stones usually partially covered with thatch, with the thatching growing as the colony grows. The height of typical mounds ranges from 25mm to 500mm, although larger heights are common with mounds reaching nearly 2m in some cases. An important feature is a large brood chamber in the center of the thatch in which all the brood is kept. Sather (1972) provides a comprehensive account of the growth and maturity of mound structure. In large colonies workers are known to chew bark at the base of plants growing on or near the mound and spray formic acid into the open layer to kill the plant.

Colonies are polydomous (single colonies have multiple separate nests) and polygynous (single colonies have multiple queens). The number of workers and individual mounds in a colony can be exceptionally high. Near Lehman Hot Springs, Blue Mountains, Oregon, a supercolony was found that occupied an area of 4 hectares and consisted of 210 active nests with an estimated population in excess of 56 million (McIver et al., 1997).

Mounds are thought to collect solar radiation, providing warming during cooler periods, while the organic material may generally moderate temperatures and humidity levels within the nest.

Nest site selected in open areas devoid of cover. Nest begun at the base of some small plant (frequently sagebrush). Extensive use made of thatching. The finished nest consisting of a large mound of collected detritus. (Creighton, 1940)

Feeding

Formica obscuripes are general omnivore-predators, obtaining food primarily by scavenging or preying upon insects and other arthropods. Foraging takes place both on the ground and on vegetation, including high in trees. They also harvest honeydew from aphids and other homopterans and are known to occasionally eat plant tissue.

Colony Founding

These ants are temporary social parasites of Formica fusca-group species, including Formica pacifica. New colonies are established when an inseminated F. obscuripes queen enters the nest of a Formica fusca-group species and is accepted by the host workers. The host queen is eventually killed or driven off, and the host workers raise the brood of the invading queen. Eventually, only F. obscuripes workers remain as the original host workers die off.

Nevada

Wheeler and Wheeler (1986) provide the following notes on this species in Nevada:

Formica obscuripes is scattered throughout the state north of the Hot Desert (i.e., north of latitude 38°N). We have 60 records from 44 localities; 4,300-10,480 ft. (80% between 5,000 and 9,000 ft.). Twenty of the records were from the Cool Desert (l from a Sarcobatus Subclimax and 1 from a disturbed area), 5 were from the Pinyon-Juniper Biome, 6 were from the Coniferous Forest Biome, and I was from the Alpine Biome. The nest is typically a dome-shaped thatch mound which was usually circular in basal outline but often elliptical. The thatch was mounted on an earthen base 5-8 cm high and was greater in diameter (43-150 cm, average 88 cm) than the thatch. The thatch itself was piled in the center of this base and measured 30-138 cm (average 66 cm) in diameter and 13-43 cm (average 30 cm) in height. The composition of the thatch was opportunistically determined, i.e., it depended upon the available plant material. Apparently when a favorite material was sufficiently abundant, the thatch was homogeneous; this was true especially of pine needles and juniper sprays. There are numerous entrances throughout the thatch; we counted at least 50 in one mound. The foregoing might be called typical, but many variants occurred; e.g., 2 nests were under stones and 1 was under a log lying on the ground. A common variant was a long pile of messy thatch along a prostrate sagebrush trunk.

Colonies were populous and the workers were very aggressive. When a colony was disturbed the surface of the mound was soon covered with workers. Many assumed the defensive position: head up and mandibles widely spread; gaster turned forward under the thorax and ready to spray formic acid into any wound made by the mandibles. Many workers started spraying at the beginning of the disturbance and soon there was an invisible cloud of formic acid vapor above the nest that was irritating to human eyes and noses. The bites of the workers were also annoying.

Under normal conditions workers would not expose themselves to direct sunlight during the hot hours of the day, but they worked diligently in any shaded areas no matter how small. Just what they were doing was hard to determine. Seemingly they were removing sticks from the thatch and putting them back at a slightly different angle.

This species was tending Aphis incognita (Hottes and Frison) at Bunker Hill (-16N-43), Lander Co., 8,100 ft. and Brevicorne symphoricarpi (Thomas) (both Homoptera: Aphididae; det. W.B. Stoetzel) on Symphoricarpos vaccinoides, on Murry Summit, White Pine Co., 8,200 ft.

Assocation with Other Species

Nests of Formica obscuripes provide a home for many insects and other athropods. These include species of beetles (Cremastocheilus, Euphoriaspis hirtipes, Haeterius), pseudoscorpians, springtails, hemipterans and dipterans (Microdon xanthopilis). The larvae of these species often use the thatch or chambers in the nest for hibernation or development and also feed on decaying matter. Formica obscuripes is also the primary host of the inquiline ant species Formica talbotae and the xenobiotic Formicoxenus diversipilosus and Formicoxenus hirticornis.

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis asclepiadis (a trophobiont) (Addicott, 1979a; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis salicariae (a trophobiont) (Addicott, 1979a; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis varians (a trophobiont) (Addicott, 1978; Addicott, 1979a; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Pleotrichophorus utensis (a trophobiont) (Billick et al., 2007; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Uroleucon escalantii (a trophobiont) (Billick et al., 2007; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a host for the crickets Myrmecophilus manni and Myrmecophilus nebrascensis.

- This species is a host for the tenebrionid beetle Alaudes singularis (a myrmecophile).

- This species is a host for the eurytomid wasp Sycophila sp. (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (associate).

- This species is a host for the braconid wasp Elasmosoma michaeli (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission outside nest).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon albicomatus (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon cothurnatus (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon piperi (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon tristis (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

Flight Period

| X | X | ||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info (April). Notes: Washington (May).

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Life History Traits

- Queen number: polygynous (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

- Queen mating frequency: single (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

Castes

Worker

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0005389. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by UCDC, Davis, CA, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- obscuripes. Formica rufa r. obscuripes Forel, 1886b: xxxix (w.) U.S.A. Emery, 1893i: 650 (q.m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1953c: 165 (l.); Hung, 1969: 456 (k.). Raised to species: Creighton, 1950a: 492. Senior synonym of aggerans: Forel, 1914c: 619; Creighton, 1940a: 1; of melanotica: Creighton, 1950a: 492. Material of the unavailable name rubiginosa referred here by Creighton, 1940a: 1. See also: Weber, 1935: 165.

- aggerans. Formica rufa subsp. aggerans Wheeler, W.M. 1912c: 90 (w.) U.S.A. Wheeler, W.M. 1913f: 430 (q.m.). Junior synonym of obscuripes: Forel, 1914c: 619; Creighton, 1940a: 1.

- melanotica. Formica rufa subsp. melanotica Creighton, 1940a: 1, fig. 1 (w.q.m.) U.S.A. [First available use of Formica rufa subsp. obscuriventris var. melanotica Emery, 1893i: 650; unavailable name.] Junior synonym of obscuripes: Creighton, 1950a: 492.

Description

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- n = 26 (USA) (Hung, 1969).

Worker Morphology

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Worker Morphology data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- Caste: weakly polymorphic

References

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Beattie, A., D. Culver. 1977. Effects of the Mound Nests of the Ant, Formica obscuripes, on the Surrounding Vegetation. American Midland Naturalist, 97/2: 390-399.

- Berg-Binder, M., A. Suarez. 2012. Testing the directed dispersal hypothesis: are native ant mounds (Formica sp.) favorable microhabitats for an invasive plant?. Oecologia, 169/2: 763-772.

- Billick, I., C. Carter. 2007. Testing the importance of the distribution of worker sizes to colony performance in the ant species Formica obscuripes Forel. Insectes Sociaux, 54/2: 113-117.

- Borowiec, M.L., Cover, S.P., Rabeling, C. 2021. The evolution of social parasitism in Formica ants revealed by a global phylogeny. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2026029118 (doi:10.1073/pnas.2026029118).

- Cantone S. 2017. Winged Ants, The Male, Dichotomous key to genera of winged male ants in the World, Behavioral ecology of mating flight (self-published).

- Carroll, T.M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). M.S. thesis, Purdue University.

- Clark, W., P. Blom. 1991. Observations of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae, Formicinae, Dolichoderinae) Utilizing Carrion. The Southwestern Naturalist, 36/1: 140-142.

- Cole, A. C. Jr. 1932. The Thatching Ant, Formica Obscuripes Forel Psyche Volume 39 (1932), Issue 1-2, Pages 30-33.

- Conway, J. 1996. A field study of the nesting ecology of the thatching ant, Formica obscuripes Forel, at high altitude in Colorado. Great Basin Naturalist, 56/4: 326-332.

- Conway, J. 1997. Foraging activity, trails, food sources, and predators of Formica obscuripes Forel (Hymenoptera:Formicidae) at high altitude in Colorado. Pan-Pacific Entomologist, 73/3: 172-183.

- Conway, J.R. 1996. Nuptial, Pre-, and Postnuptial Activity of the Thatching Ant, Formica obscuripes Forel, in Colorado. Great Basin Naturalist, 56(1), 1996, pp. 54-58

- Creighton, W. S. 1940a. A revision of the North American variants of the ant Formica rufa. American Museum Novitates 1055: 1-10. (page 1, Material of the unavailable name rubiginosa referred here.)

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 492, Raised to species)

- Crutsinger, G., N. Sanders. 2005. Aphid-Tending Ants Affect Secondary Users in Leaf Shelters and Rates of Herbivory on Salix hookeriana in a Coastal Dune Habitat. American Midland Naturalist, 154/2: 296-304.

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- Emery, C. 1893k. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Geogr. Biol. Tiere 7: 633-682 (page 650, queen, male described)

- Erickson, D., E. Wood, K. Oliver, I. Billick, P. Abbot. 2012. The Effect of Ants on the Population Dynamics of a Protective Symbiont of Aphids, Hamiltonella defensa. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 105/3: 447-453.

- Forel, A. 1886c. Diagnoses provisoires de quelques espèces nouvelles de fourmis de Madagascar, récoltées par M. Grandidier. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 30:ci-cvii. (page xxix, worker described)

- Forel, A. 1914c. Einige amerikanische Ameisen. Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 1914: 615-620 (page 619, Senior synonym of aggerans)

- Fraser, A., A. Axen, N. Pierce. 2001. Assessing the quality of different ant species as partners of a myrmecophilous butterfly. Oecologia, 129/3: 452-460.

- Grinath, J., B. Inouye, N. Underwood, I. Billick. 2012. The indirect consequences of a mutualism: comparing positive and negative components of the net interaction between honeydew-tending ants and host plants. Journal of Animal Ecology, 81/2: 494-502.

- Heikkinen, M. 1999. Negative effects of the western thatching ant (Formica obscuripes) on spiders (Araneae) inhabiting big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata). Great Basin Naturalist, 59/4: 380-383.

- Henderson, G., R. Akre. 1986. Biology of the Myrmecophilous Cricket, Myrmecophilus manni (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 59/3: 454-467.

- Herbers, J. 1979. Caste-biased Polyethism in a Mound-building Ant Species. American Midland Naturalist. 101(1):69-75.

- Herbers, J. M. 1977. Behavioral constancy in Formica obscuripes (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 70:485-486. doi:10.1093/aesa/70.4.485

- Higgins, R., B. Lindgren. 2012. An evaluation of methods for sampling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Entomologist, 144/3: 491-507.

- Higgins, R.J., Lindgren, B.S. 2012. An evaluation of methods for sampling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in British Columbia, Canada. The Canadian Entomologist 144, 491–507 (doi:10.4039/tce.2012.50).

- Hung, A. C. F. 1969. The chromosome numbers of six species of formicine ants. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 62: 455-456 (page 455, karyotype described)

- Jurgensen, M.F., Storer, A.J. & Risch, A.C. 2005. Red Wood Ants in North America. Ann. Zool. Fennici 42:235-242, Helsinki, 28 June, 2005

- Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY.

- McIver, J., K. Yandell. 1998. Honeydew harvest in the western thatching ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). American Entomologist, 44/1: 30-35.

- McIver, J., T. Steen. 1994. Use of a secondary nests in Great Basin desert thatch ants (Formica obscuripes Forel). Great Basin Naturalist, 54/4: 359-365.

- McIver, J., Torgersen, T., Cimon, N. 1997. A supercolony of the thatch ant Formica obscuripes Forel (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Blue Mountains of Oregon. Northwest Science, 71/1: 18-29.

- Mico, E., A. Smith, M. Moron. 2000. New Larval Descriptions for Two Species of Euphoria Burmeister (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Cetoniinae: Cetoniini: Euphoriina) with a Key to the Known Larvae and a Review of the Larval Biology. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 93/4: 795-801.

- Rericha, L. 2007. Ants of Indiana. Indiana Department of Natural Resources, 51pp.

- Risch, A., M. Jurgensen, A. Storer, M. Hyselop, M. Schutz. 2008. Abundance and distribution of organic mound-building ants of the Formica rufa group in Yellowstone National Park. Journal of Applied Entomology, 132/4: 326-336.

- Sather, D.A. 1972. Nest morphogenesis and population ecology of two species of Formica. Ph. D. thesis, University of North Dakota.

- Seibert, T. 1992. Mutualistic interactions of the aphid Lachnus allegheniensis (Homoptera, Aphididae) and its tending ant Formica obscuripes (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 85/2: 173-178.

- Seibert, T. 1993. A nectar-secreting gall wasp and ant mutualism - selection and counter-selection shaping gall wasp phenology, fecundity, and persistence. Ecological Entomology, 18/3: 247-253.

- Shaw, S. 2007. A new species of Elasmosoma ruthe (Hymenoptera : Braconidae : Neoneurtnae) from the northwestern United States associated with the western thatching ants, Formica obscuripes Forel and Formica obscuriventris clivia Creighton (Hymenoptera : Formicidae). Proceedings on the Entomological Society of Washington, 109/1: 1-8.

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Talbot, M. 1972. Flights and Swarms of the Ant Formica obscuripes Forel. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 45/2: 254-258.

- Tilman, D. 1978. Cherries, Ants and Tent Caterpillars: Timing of Nectar Production in Relation to Susceptibility of Caterpillars to Ant Predation. Ecology, 59/4: 686-692.

- Ward, P. S., 2005, A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)., Zootaxa, pp. 1-68, vol. 936

- Weber, N. A. 1935. The biology of the thatching ant, Formica rufa obscuripes Forel, in North Dakota. Ecol. Monogr. 5: 165-206.

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1953c. The ant larvae of the subfamily Formicinae. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 46: 126-171 (page 165, larva described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Allred D. M. 1982. Ants of Utah. The Great Basin Naturalist 42: 415-511.

- Allred, D.M. 1982. The ants of Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 42:415-511.

- Alpert G. D., and R. D. Akre. 1973. Distribution, abundance, and behavior of the inquiline ant Leptothorax diversipilosus. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 66: 753-760.

- Beck D. E., D. M. Allred, W. J. Despain. 1967. Predaceous-scavenger ants in Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 27: 67-78

- Bestelmeyer B. T., and J. A. Wiens. 2001. Local and regional-scale responses of ant diversity to a semiarid biome transition. Ecography 24: 381-392.

- Blacker, N.C. 1992. Some Ants from Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. J. Entomol. Soc. Bri. Columbia 89:3-12.

- Blacker, N.C. 1992. Some ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 89:3-12

- Borchert, H.F. and N.L. Anderson. 1973. The Ants of the Bearpaw Mountains of Montana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 46(2):200-224

- Buren W. F. 1944. A list of Iowa ants. Iowa State College Journal of Science 18:277-312

- Carroll T. M. 2011. The ants of Indiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Master's Thesis Purdue university, 385 pages.

- Clark Adam. Personal communication on November 25th 2013.

- Clark W. H., and P. E. Blom. 1991. Observations of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae, Formicinae, Dolichoderinae) utilizing carrion. The Southwestern Naturalist 36(1): 140-142.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1934. An annotated list of the ants of the Snake River Plains, Idaho (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (Cambridge) 41: 221-227.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68: 34-39.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1937. An annotated list of the ants of Arizona (Hym.: Formicidae). [concl.]. Entomological News 48: 134-140.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Cole, A.C. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68(2):34-39

- Coovert, G.A. 2005. The Ants of Ohio (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin New Series Volume 15(2):1-196

- Downing H., and J. Clark. 2018. Ant biodiversity in the Northern Black Hills, South Dakota (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 91(2): 119-132.

- Dubois, M.B. and W.E. Laberge. 1988. An Annotated list of the ants of Illionois. pages 133-156 in Advances in Myrmecology, J. Trager

- Glasier J. R. N., S. Nielsen, J. H. Acorn, L. H. Borysenko, and T. Radtke. 2016. A checklist of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Saskatchewan. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 130(1): 40-48.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Kannowski P. B. 1956. The ants of Ramsey County, North Dakota. American Midland Naturalist 56(1): 168-185.

- Kittelson P. M., M. P. Priebe, and P. J. Graeve. 2008. Ant Diversity in Two Southern Minnesota Tallgrass Prairie Restoration Sites. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 115(14): 2832.

- Knowlton G. F. 1970. Ants of Curlew Valley. Proceedings of the Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 47(1): 208-212.

- La Rivers I. 1968. A first listing of the ants of Nevada. Biological Society of Nevada, Occasional Papers 17: 1-12.

- Lavigne R., and T. J. Tepedino. 1976. Checklist of the insects in Wyoming. I. Hymenoptera. Agric. Exp. Sta., Univ. Wyoming Res. J. 106: 24-26.

- Lidgren, B.S. and A.M. MacIsaac. 2002. A Preliminary Study of Ant Diversity and of Ant Dependence on Dead Wood in Central Interior British Columbia. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-181.

- Lindgren, B.S. and A.M. MacIsaac. 2002. Ant dependence on dead wood in Central Interior British Columbia. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep.PSW-GTR-181

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Mackay W. P., and E. E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- Mackay, W., D. Lowrie, A. Fisher, E. Mackay, F. Barnes and D. Lowrie. 1988. The ants of Los Alamos County, New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). pages 79-131 in J.C. Trager, editor, Advances in Myrmecololgy.

- Mallis A. 1941. A list of the ants of California with notes on their habits and distribution. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 40: 61-100.

- McIver J. D., T. R. Torgersen, and N. J. Cimon. 1997. A supercolony of the thach ant Formica obscuripes Forel (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Blue Mountains of Oregon. Northwest Science 71(1): 18-29.

- Menke S. B., E. Gaulke, A. Hamel, and N. Vachter. 2015. The effects of restoration age and prescribed burns on grassland ant community structure. Environmental Entomology http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvv110

- Munsee, J. R.; Jansma, W. B.; Schrock, J. R. 1986. Revision of the checklist of Indiana ants with the addition of five new species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1985, publ. 1986 Vol. 95 pp. 265-274

- Paulsen, M.J. 2002. Observations on possible myrmecophily in Stephanucha pilipennis Kraatz (Coleoptera: Scarabaedidae: Cetoniinae) in Western Nebraska. Coleopterists Bulletin 56(3):451-452

- Rees D. M., and A. W. Grundmann. 1940. A preliminary list of the ants of Utah. Bulletin of the University of Utah, 31(5): 1-12.

- Sharplin, J. 1966. An annotated list of the Formicidae (Hymenoptera) of Central and Southern Alberta. Quaetiones Entomoligcae 2:243-253

- Smith M. R. 1928. An additional annotated list of the ants of Mississippi. With a description of a new species of Aphaenogaster (Hym.: Formicidae) (continued from page 246). Entomological News 39: 275-279.

- Smith M. R. 1952. On the collection of ants made by Titus Ulke in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the early nineties. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 60: 55-63.

- Talbot M. 1976. A list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Edwin S. George Reserve, Livingston County, Michigan. Great Lakes Entomologist 8: 245-246.

- Talbot M. 1977. The natural history of the workerless ant parasite Formica talbotae. Psyche (Cambridge) 83: 282-288.

- Weber N. A. 1935. The biology of the thatching ant, Formica rufa obscuripes Forel, in North Dakota. Ecol. Monogr. 5: 165-206.

- Wheeler G. C., J. N. Wheeler, and P. B. Kannowski. 1994. Checklist of the ants of Michigan (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Great Lakes Entomologist 26(4): 297-310

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1987. A Checklist of the Ants of South Dakota. Prairie Nat. 19(3): 199-208.

- Wheeler W. M. 1913. A revision of the ants of the genus Formica (Linné) Mayr. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 53: 379-565.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. The mountain ants of western North America. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 52: 457-569.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1978. Mountain ants of Nevada. Great Basin Naturalist 35(4):379-396

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Montana. Psyche 95:101-114

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Wyoming. Insecta Mundi 2(3&4):230-239

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler and P.B. Kannowski. 1994. CHECKLIST OF THE ANTS OF MICHIGAN (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE). Great Lakes Entomologist 26:1:297-310

- Wheeler, G.C., J. Wheeler, T.D. Galloway and G.L. Ayre. 1989. A list of the ants of Manitoba. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Manitoba 45:34-49

- Wilson E. O. 1977. The first workerless parasite in the ant genus Formica (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (Cambridge) 83: 277-281.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- Polygynous

- Temporary parasite

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Nesting Notes

- Ant Associate

- Host of Formica pacifica

- ''Microdon'' fly Associate

- Host of Microdon xanthopilis

- Host of Formica talbotae

- Host of Formicoxenus diversipilosus

- Host of Formicoxenus hirticornis

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis asclepiadis

- Host of Aphis salicariae

- Host of Aphis varians

- Host of Pleotrichophorus utensis

- Host of Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae

- Host of Uroleucon escalantii

- Cricket Associate

- Host of Myrmecophilus manni

- Host of Myrmecophilus nebrascensis

- Tenebrionid beetle Associate

- Host of Alaudes singularis

- Eurytomid wasp Associate

- Host of Sycophila sp.

- Braconid wasp Associate

- Host of Elasmosoma michaeli

- Host of Microdon albicomatus

- Host of Microdon cothurnatus

- Host of Microdon piperi

- Host of Microdon tristis

- FlightMonth

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Formicinae

- Formicini

- Formica

- Formica obscuripes

- Formicinae species

- Formicini species

- Formica species

- Need Body Text

- Rufa group

- Ssr