Acromyrmex echinatior

| Acromyrmex echinatior | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Acromyrmex |

| Species: | A. echinatior |

| Binomial name | |

| Acromyrmex echinatior (Forel, 1899) | |

Acromyrmex echinatior is a host species of the social parasite Acromyrmex insinuator.

Identification

Schultz et al. (1998) - Acromyrmex octospinosus var. echinatior was described by Forel (1900) and elevated to subspecies status by Wheeler (1937). These authors, as well as Santschi (1925), recognized A. octospinosus echinatior principally by the sculpture of the head and gaster of the major worker: “the tubercles on the posterior corners of the head, the pedicel, and the gaster are more developed and subspiniform, and some of those on the sides of the head are distinctly curved forward” (Wheeler, 1937).

WORKERS: In the fifty nests excavated in Panama, the largest major workers of A. echinatior are the same size as those of Acromyrmex octospinosus. However, a previous study by Bot and Boomsma (1997) found that pronotum width in A. echinatior (species 1 in that study) was significantly smaller than pronotum width in A. octospinosus (species 2 in that study). Qualitatively, major workers of the two species differ in the following ways: In A. echinatior the lateral pronotal spines are nearly vertical and parallel in frontal view, the vertical angle noticeably different from the angle of the anterior mesonotal spines, which diverge. In A. octospinosus, the anterior spines are not vertical and both pairs of spines diverge at approximately the same angle. Major workers of A. echinatior are hairier than those of A. octospinosus; e. g., at least some setae are present on the face of the propodeal dorsum in addition to those associated with the propodeal spines and with the anterior tubercles, whereas in A. octospinosus such setae are absent. In general, tubercles on the gaster of A. echinatior workers are sharp and dentiform to subspiniform, whereas those in A. octospinosus are low and blunted. Likewise, tubercles on the head of A. echinatior are sharp and spiniform, whereas those of A. octospinosus are shorter and blunter. We caution, however, that there is overlap between the two species in the form of the spines of the gaster and head and that these commonly cited characters are therefore not entirely reliable. Worker color is quite variable, ranging from yellow in callows to yellowish-ferrugineous to ferrugineous, with, as noted by Wheeler (1937) some workers acquiring a “bluish bloom.”

When workers from the entire range of both species are taken into account, the most constant distinguishing characters are the form of the spines on the head and gaster and to a lesser extent the differing angles of the lateral pronotal vs. anterior mesonotal spines. Major workers of A. echinatior from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico, including the lectotype, frequently lack setae on the propodeal dorsum and are often much larger than those from the Panamanian nests.

FEMALES: In the Panamanian nests, A. echinatior females are smaller than Acromyrmex octospinosus females, and differ from them in the presence of a pigment spot entirely surrounding the ocelli (absent in the Panamanian A. octospinosus), the presence of setae on the propodeal dorsum (absent in A. octospinosus), and the presence of a broadly convex median anteroventral postpetiolar extension (variable in A. octospinosus). The occipital tubercle is thin and sharp and the tubercles on the first gastric tergite are sharp and dentiform; in A. octospinosus the occipital tubercle is thick and blunt, and the gastric tubercles are blunt and rounded. Color variation in females corresponds to that in workers. Over the whole of the species’ Central American range, A. echinatior females are more variable in size than in the Panamanian sample, tending to be larger, and variable in the presence/absence of the ocellar pigment spot.

MALES: In the Panamanian nests, A. echinatior males are the same size as A. octospinosus males, but differ from them by the presence of a pigmented frontal triangle that is entirely delineated by rugae (unpigmented and ill-defined in A. octospinosus), the presence of setae on the propodeal dorsum (absent in A. octospinosus), and the presence of a broadly convex median anteroventral postpetiolar extension (variable in A. octospinosus). Color is yellow-ferrugineous. A. echinatior males over the rest of the species’ range are variable in the characters of the frontal triangle.

Assigning the Panamanian specimens to A. echinatior is not without problems. The largest Panamanian workers are smaller than the lectotype and smaller than other worker specimens from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico. Differences also exist in the characters of the propodeal setae (all castes), the ocellar pigment spot in females, and the form of the frontal triangle in males. Although the conservative position taken here is that these differences fall within the normal range of variation expected from a species distributed over a wide area, we would not be at all surprised to find that both Acromyrmex octospinosus sensu lato and Acromyrmex echinatior are composed of a number of cryptic species. If this is established by future research, then the Panamanian host of Acromyrmex insinuator may require species status separate from A. echinatior.

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 18.62° to 8.808°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico (type locality), Nicaragua, Panama.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Nehring et al. (2015) - This species and the sympatric Acromyrmex octospinosus are both parasitized by Acromyrmex insinuator but the parasitic queens are only able to successfully reproduce in A. echinatior nests.

Reproduction

Liberti et al. (2018) studied sperm competition in this species. Queens of A. echinatior mate with multiple males. An earlier study (Liberti et al. 2016) found that queens produce reproductive tract fluid that enhances sperm motility. This increases the possibility that the subsequently stored sperm is viable. This current study found sperm motility increased when exposed to other male ejaculates. This increased activity was similar to what was observed with exposure to reproductive tract fluid in queens. Liberti et al. concluded "Our results suggest that ant sperm respond via a self–non-self recognition mechanism to similar or shared molecules expressed in the reproductive secretions of both sexes. Lower sperm motility in the presence of own seminal fluid indicates that enhanced motility is costly and may trade-off with sperm viability during sperm storage, consistent with studies in vertebrates. Our results imply that ant spermatozoa have evolved to adjust their energetic expenditure during insemination depending on the perceived level of sperm competition."

Genetics

Acromyrmex echinatior has had their entire genome sequenced.

Palomeque et al. (2015) found class II mariner elements, a form of transposable elements, in the genome of this ant.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the fungus Aspergillus flavus (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode primary; direct transmission; transmission within nest).

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

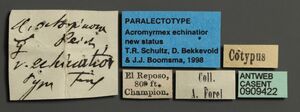

| Paralectotype of Acromyrmex echinatior. Worker. Specimen code casent0909422. Photographer Will Ericson, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MHNG, Geneva, Switzerland. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- echinatior. Atta (Acromyrmex) octospinosa var. echinatior Forel, 1899c: 34 (w.q.) MEXICO (Chihuahua), GUATEMALA, COSTA RICA, PANAMA.

- Type-material: lectotype worker (by designation of Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998: 461), paralectotype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: lectotype Guatemala: Vera Paz, Senahu, El Reposo, Zapota, 800 ft (Champion); paralectotypes: with same data and from other original syntype localities.

- [Note: other original syntype localities: Mexico: Chihuahua, Montezuma (Cockerell), Costa Rica: Volcán de Irazu (Rogers), Panama: Volcán de Chiriqui, Bugaba (Champion) (invalid restriction of type-locality by Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 72 (in text); no lectotype designated).]

- Type-depository: MHNG.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 72 (m.).

- Combination in Acromyrmex: Emery, 1924d: 350.

- Junior synonym of octospinosus: Emery, 1905c: 44.

- Subspecies of octospinosus: Forel, 1912e: 181; Emery, 1924d: 350; Santschi, 1925a: 391 (in key); Wheeler, W.M. 1937c: 71; Wheeler, W.M. 1938: 252; Santschi, 1939e: 319 (in key); Santschi, 1939f: 166 (in key); Weber, 1941b: 125; Kempf, 1972a: 14; Bolton, 1995b: 55.

- Status as species: Schultz, Bekkevold & Boomsma, 1998: 460; Branstetter & Sáenz, 2012: 257.

- Distribution: Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Type Material

Schultz et al. (1998) - LECTOTYPE: Major worker. Guatemala: Senahuen Vera Paz, El Reposo, Zapote, 800 ft. (Champion). A. Forel Collection, Muséum d’Histoire naturelle, Geneva, Switzerland. Paratypes examined: 2 minor workers: Guatemala: Senahuen Vera Paz, El Reposo, 800 ft. (Champion). 1 alate and 1 dealate female: Panama: Volcan de Chiriquí, 25–1000 ft. (Champion). 2 alate females: Panama: Bugaba (Champion).

The list of specimens published in Forel’s (1899) description includes two workers, one from Guatemala and one from Costa Rica, the latter now apparently lost. Forel (1899) did not designate a holotype; five pins (seven specimens) in the syntype series bear the designation “type” written in Forel’s hand. Affixed to two of Forel’s syntype pins, one bearing a single major worker, the other bearing two females, are red “Typus” labels, but these may have been added subsequently and at any rate have no formal standing. Wheeler (1937) designated the type locality of A. octospinosus echinatior as Volcan de Chiriquí, Panama, the collection locality of two of Forel’s syntype females, but did not designate a lectotype. We have chosen to ignore this action and to designate the only remaining major worker in Forel’s syntype series as the lectotype for two important reasons: (1) species concepts in Acromyrmex are based entirely upon the characters of major workers and (2) Forel’s syntype females vary in size and collection locality, raising the possibility that they represent multiple species.

Description

Worker

Schultz et al. (1998) - LECTOTYPE: HL = 2.16; HW = 2.64; WL = 3.72; SL = 2.64; maximum diameter of eye = 0.43.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- 2n = 38, karyotype = 8M+6SM+14ST+10A (Brazil) (Barros et al., 2016).

References

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Barros, L.A.C., Aguiar, H.J.A.C., Teixeira, G.C., Souza, D.J., Delabie, J.H.C., Mariano, C.S.F. 2021. Cytogenetic studies on the social parasite Acromyrmex ameliae (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) and its hosts reveal chromosome fusion in Acromyrmex. Zoologischer Anzeiger 293, 273–281 (doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2021.06.012).

- Borowiec, M.L. 2019. Convergent evolution of the army ant syndrome and congruence in big-data phylogenetics. Systematic Biology 68, 642–656 (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy088).

- Branstetter, M.G., Danforth, B.N., Pitts, J.P., Faircloth, B.C., Ward, P.S., Buffington, M.L., Gates, M.W., Kula, R.R., Brady, S.G. 2017. Phylogenomic insights into the evolution of stinging wasps and the origins of ants and bees. Current Biology 27, 1019–1025 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.027).

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Cardoso, D. C., Cristiano, M. P. 2021. Karyotype diversity, mode, and tempo of the chromosomal evolution of Attina (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini): Is there an upper limit to chromosome number? Insects 1212, 1084 (doi:10.3390/insects12121084).

- Casacci, L.P., Barbero, F., Slipinski, P., Witek, M. 2021. The inquiline ant Myrmica karavajevi uses both chemical and vibroacoustic deception mechanisms to integrate into its host colonies. Biology 10, 654 (doi:10.3390/ biology10070654)..

- Chernyshova, A.M. 2021. A genetic perspective on social insect castes: A synthetic review and empirical study. M.S. thesis, The University of Western Ontario. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7771.

- Dahan, R.A., Grove, N.K., Bollazzi, M., Gerstner, B.P., Rabeling, C. 2021. Decoupled evolution of mating biology and social structure in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 76, 7 (doi:10.1007/s00265-021-03113-1).

- de Bekker, C., Will, I., Das, B., Adams, R.M.M. 2018. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and their parasites: effects of parasitic manipulations and host responses on ant behavioral ecology. Myrmecological News 28: 1-24 (doi:10.25849/myrmecol.news_028:001).

- de la Mora, A., Sankovitz, M., Purcell, J. 2020. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as host and intruder: recent advances and future directions in the study of exploitative strategies. Myrmecological News 30: 53-71 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:053).

- Emery, C. 1924f [1922]. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Myrmicinae. [concl.]. Genera Insectorum 174C: 207-397 (page 350, Combination in Acromyrmex)

- Farder-Gomes, C.F., Oliveira, M.A., Castro Della Lucia, T.M., Serrão, J.E. 2019. Morphology of the ovary and spermatheca of the leafcutter ant Acromyrmex rugosus queens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 102, 515-519 (doi:10.1653/024.102.0312).

- Forel, A. 1899d. Formicidae. [part]. Biol. Cent.-Am. Hym. 3: 25-56 (page 34, worker, queen described)

- Hamilton, N., Jones, T.H., Shik, J.Z., Wall, B., Schultz, T.R., Blair, H.A., Adams, R.M.M. 2018. Context is everything: mapping Cyphomyrmex-derived compounds to the fungus-growing ant phylogeny. Chemoecology 28, 137–144. (doi:10.1007/S00049-018-0265-5).

- Jacobs, S. 2020. Population genetic and behavioral aspects of male mating monopolies in Cardiocondyla venustula (Ph.D. thesis).

- Lau, M.K., Ellison, A.M., Nguyen, A., Penick, C., DeMarco, B., Gotelli, N.J., Sanders, N.J., Dunn, R.R., Helms Cahan, S. 2019. Draft Aphaenogaster genomes expand our view of ant genome size variation across climate gradients. PeerJ 7, e6447 (doi:10.7717/PEERJ.6447).

- Liberti, J., B. Baer, and J. J. Boomsma. 2016. Queen reproductive tract secretions enhance sperm motility in ants. Biology Letters. 12:20160722. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0722

- Liberti, J., B. Baer, and J. J. Boomsma. 2018. Rival seminal fluid induces enhanced sperm motility in a polyandrous ant. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 18:12. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1144-y

- Liberti, J., Sapountzis, P., Hansen, L.H., Sørensen, S.J., Adams, R.M.M., Boomsma, J.J. 2015. Bacterial symbiont sharing in Megalomyrmex social parasites and their fungus-growing ant hosts. Molecular Ecology 24, 3151–3169 (doi:10.1111/MEC.13216).

- Lo, N., Beekman, M., Oldroyd, B.P. 2019. Caste in social insects: Genetic influences over caste determination. In: Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior (Second Edition), pp. 274–281 (doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20759-0).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Mueller, U.G., Ishak, H.D., Bruschi, S.M., Smith, C.C., Herman, J.J., Solomon, S.E., Mikheyev, A.S., Rabeling, C., Scott, J.J., Cooper, M., Rodrigues, A., Ortiz, A., Brandão, C.R.F., Lattke, J.E., Pagnocca, F.C., Rehner, S.A., Schultz, T.R., Vasconcelos, H.L., Adams, R.M.M., Bollazzi, M., Clark, R.M., Himler, A.G., LaPolla, J.S., Leal, I.R., Johnson, R.A., Roces, F., Sosa-Calvo, J., Wirth, R., Bacci, M. 2017. Biogeography of mutualistic fungi cultivated by leafcutter ants. Molecular Ecology 26, 6921–6937 (doi:10.1111/mec.14431).

- Nagel, M., Qiu, B., Brandenborg, L.E., Larsen, R.S., Ning, D., Boomsma, J.J., Zhang, G. 2020. The gene expression network regulating queen brain remodeling after insemination and its parallel use in ants with reproductive workers. Science Advances 6, eaaz5772 (doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz5772).

- Nehring, V., Boomsma, J.J., d'Ettorre, P. 2012. Wingless virgin queens assume helper roles in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Current Biology 22, R671–R673 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.038).

- Nehring, V., F. R. Dani, S. Turillazzi, J. J. Boomsma, and P. d'Ettorre. 2015. Integration strategies of a leaf-cutting ant social parasite. Animal Behaviour. 108:55-65. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.07.009

- Palomeque, T., O. Sanllorente, X. Maside, J. Vela, P. Mora, M. I. Torres, G. Periquet, and P. Lorite. 2015. Evolutionary history of the Azteca-like mariner transposons and their host ants. Science of Nature. 102. doi:10.1007/s00114-015-1294-3

- Qiu, B., Larsen, R.S., Chang, N.-C., Wang, J., Boomsma, J.J., Zhang, G. 2018. Towards reconstructing the ancestral brain gene-network regulating caste differentiation in ants. Nature Ecology, Evolution 2, 1782–1791. (doi:10.1038/S41559-018-0689-X).

- Ronque, M.U.V., Lyra, M.L., Migliorini, G.H., Bacci, M., Oliveira, P.S. 2020. Symbiotic bacterial communities in rainforest fungus-farming ants: evidence for species and colony specificity. Scientific Reports 10, 10172 (doi:10.1038/S41598-020-66772-6).

- Roux, J., Privman, E., Moretti, S., Daub, J.T., Robinson-Rechavi, M., Keller, L. 2014. Patterns of positive selection in seven ant genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31, 1661–1685 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msu141).

- Sanne Nygaard, Guojie Zhang, Morten Schiøtt, Cai Li, Yannick Wurm, Haofu Hu, Jiajian Zhou, Lu Ji, Feng Qiu, Morten Rasmussen, Hailin Pan, Frank Hauser, Anders Krogh, Cornelis J.P. Grimmelikhuijzen, Jun Wang and Jacobus J. Boomsma (2011) The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming. Genome Research. 21:1339-1348. doi:10.1101/gr.121392.111

- Schultner, E., Pulliainen, U. 2020. Brood recognition and discrimination in ants. Insectes Sociaux 67, 11–34 (doi:10.1007/s00040-019-00747-3).

- Schultz, T.R., Bekkevold, D. ; Boomsma, J.J. 1998. Acromyrmex insinuator new species; an incipient social parasite of fungus-growing ants. Insectes Soc. 45(4): 457-471 (page 460, Raised to species)

- Silva, J.R.da, Souza, A.Z.de, Pirovani, C.P., Costa, H., Silva, A., Dias, J.C.T., Delabie, J.H.C., Fontana, R. 2018. Assessing the proteomic activity of the venom of the ant Ectatomma tuberculatum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ectatomminae). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2018, 1–11 (doi:10.1155/2018/7915464).

- Travaglini, R.V., Forti, L.C., Arnosti, A., Stefanelli, L.E.P., Ferreira, A.R.F., Camargo, R.D.S., Camargo-Mathias, M.I. 2020. Description using ultramorphological techniques of the infection of Beauveria bassiana (Bals.-Criv.) Vuill. in larvae and adults of Atta sexdens (Linnaeus, 1758) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi - Ciências Naturais 15, 101–111 (doi:10.46357/bcnaturais.v15i1.201).

- Wheeler, W. M. 1937c. Mosaics and other anomalies among ants. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 95 pp. (page 72, male described; page 71, subspecies of octospinosus)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Ahuatzin D. A., E. J. Corro, A. Aguirre Jaimes, J. E. Valenzuela Gonzalez, R. Machado Feitosa, M. Cezar Ribeiro, J. Carlos Lopez Acosta, R. Coates, W. Dattilo. 2019. Forest cover drives leaf litter ant diversity in primary rainforest remnants within human-modified tropical landscapes. Biodiversity and Conservation 28(5): 1091-1107.

- Bekkevold, D., J. Frydenberg and J.J. Boomsma. 1999. Multiple mating and facultative polygyny in the Panamanian leafcutter ant Acromyrmex echinatior. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 46:103-109.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Forel A. 1912. Formicides néotropiques. Part II. 3me sous-famille Myrmicinae Lep. (Attini, Dacetii, Cryptocerini). Mémoires de la Société Entomologique de Belgique. 19: 179-209.

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kooij P. W., B. M. Dentinger, D. A. Donoso, J. Z. Shik, and E. Gaya. 2018. Cryptic diversity in Colombian edible leaf-cutting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insects 9: 191.

- Longino J. T. 2013. Ants of Nicargua. Consulted on 18 Jan 2013. https://sites.google.com/site/longinollama/reports/ants-of-nicaragua

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Maes, J.-M. and W.P. MacKay. 1993. Catalogo de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia 23.

- Philpott, S.M., P. Bichier, R. Rice, and R. Greenberg. 2007. Field testing ecological and economic benefits of coffee certification programs. Conservation Biology 21: 975-985.

- Poulsen, M., W.O.H. Hughes and J.J. Boomsma. 2006. Differential resistance and the importance of antibiotic production in Acromyrmex echinatior leaf-cutting ant castes towards the entomopathogenic fungus Aspergillus nomius. Insectes Sociaux 53:349-355

- Schultz T. R., D. Bekkevold, J. J. Boomsma. 1998. Acromyrmex insinuator new species; an incipient social parasite of fungus-growing ants. Insectes Soc. 45(4): 457-471.

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.

- Sumner, S., D.K. Aanen, J. Delabie and J.J. Boomsma. 2004. The evolution of social parasitism inAcromyrmexleaf-cutting ants: a test of Emerys rule. Insectes Sociaux 51(1):37-42.

- Sumner, S., W.O.H. Hughes and J.J. Boomsma. 2003. Evidence for Differential Selection and Potential Adaptive Evolution in the Worker Caste of an Inquiline Social Parasite. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 54(3):256-263

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Weber N. A. 1941. The biology of the fungus-growing ants. Part VII. The Barro Colorado Island, Canal Zone, species. Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 12: 93-130.

- Wheeler W. M. 1937. Mosaics and other anomalies among ants. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 95 pp.

- Zelikova, T.J. and M.D. Breed. 2008. Effects of habitat disturbance on ant community composition and seed dispersal by ants in a tropical dry forest in Costa Rica. Journal of Tropical Ecology 24:309-316