Trachymyrmex pomonae

| Trachymyrmex pomonae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Trachymyrmex |

| Species: | T. pomonae |

| Binomial name | |

| Trachymyrmex pomonae Rabeling & Cover, 2007 | |

A small Trachymyrmex species of open woodlands in a few mountain ranges of southwestern North America.

Identification

Probably sympatric with Trachymyrmex carinatus and Trachymyrmex arizonensis in mid elevation woodland habitats throughout much of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, but workers and queens of T. pomonae are easily recognized by their smaller size, shorter antennal scapes, notably asymmetric frontal lobes, and short preocular carinae that do not approach the frontal carinae. T. pomonae is most similar to Trachymyrmex desertorum, but is separable by its strongly asymmetric frontal lobes (weakly asymmetric at most in T. desertorum), smaller size, and different habitat preferences. (Rabeling et al. 2007)

Keys including this Species

Distribution

This species is known only from southern Arizona (Cochise and Santa Cruz Counties) and the state of Sonora, Mexico. (Rabeling et al. 2007)

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 31.89166667° to 29.26861111°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

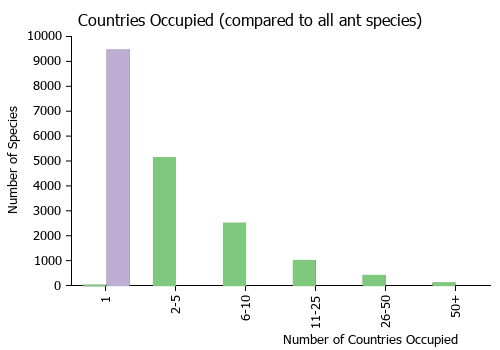

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

From Rabeling et al. (2007): Trachymyrmex pomonae is the smallest Trachymyrmex species occurring in the United States. In Arizona, T. pomonae lives sympatrically with Trachymyrmex carinatus and Trachymyrmex arizonensis in the Chiricahua, Patagonia, and Pajarito Mountains at elevations of 1200–1700 m. The open woodland habitat in these mountains is dominated by Emory and Gray Oaks (Quercus emoryi and Q. grisea), pinyon pine (Pinus edulis), juniper (Juniperus deppeana), and in some places Chihuahua Pine (Pinus leiophylla). Trachymyrmex pomonae nests in very rocky soil. Nest craters are small, approximately 5 cm in diameter, or absent. When craters are absent, the nests are difficult to find, because the entrance is minute and the ants inconspicuous. Excavated nests had 1–3 fungus chambers distributed from 5–40 cm below the surface; fungus gardens were suspended from the ceiling of the chambers. The largest colony contained 183 workers, 2 dealate queens, 45 pupae and 31 larvae. Although a nuptial flight was not observed directly, winged queens and males were found from 9–25 August in the years 1999, 2001 and 2005. Males were encountered at nest entrances, whereas winged queens were found walking on the ground. The collection dates suggest that T. pomonae disperses in the monsoon season (July–September), after heavy rainfall has softened the clayey loam soil, a habit shared with the other Trachymyrmex in Arizona. Workers forage diurnally in the leaf litter to collect vegetable debris and caterpillar feces, which they use to nourish the fungus garden.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- pomonae. Trachymyrmex pomonae Rabeling & Cover, in Rabeling, et al. 2007: 14, figs. 12-14 (w.q.m.) U.S.A. (Arizona), MEXICO (Sonora).

- Type-material: holotype worker, 110 paratype workers, 9 paratype queens, 1 paratype male.

- Type-locality: holotype U.S.A: Arizona, Cochise County, Chiricahua Mts, 0.5 km. N Southwestern Research Station, 31°53.20’N, 109°12.27’W, 5600 ft (1707 m.), 12.viii.2001, SPC 6330 (S.P. Cover); paratypes: 15 workers, 1 queen with same data, 13 workers with same data but SPC 6328, 48 workers, 8 queens, 1 male with same data but 14.viii.2001, UGM 010814-01 (U. G. Mueller), 34 workers with same data but 10.viii.2005, CR 050810-01 (C. Rabelling).

- Type-depositories: MCZC (holotype); BMNH, CASC, CRPC, LACM, MCZC, MZSP, RAJC, SMNK, UCDC, USNM, WEMC (paratypes).

- Status as species: Solomon, Rabeling, et al. 2019: 948.

- Distribution: Mexico, U.S.A.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Diagnosis from Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 0.75–0.95, HW 0.78–0.95, CI 97–103, SL 0.73–0.88, SI 89–100, ML 1.0–1.28. The smallest species of Trachymyrmex in the US (HL 0.75–0.95; HW 0.78–0.95), with relatively short legs and antennal scapes (SI 89–100). Head quadrate (CI 97–103), sides subparallel behind the level of the eye, moderately tapering anteriorly between the eye and mandibular insertion. Posterior margin slightly to moderately concave. In full-face view, preocular carinae short, traversing only about half the distance between the eye and the frontal carinae. Frontal lobes subtriangular or rounded in full-face view, notably asymmetric with the anterior side of the lobe markedly longer than the posterior. Mesosomal teeth generally small in size, sometimes reduced to tubercles. Anterolateral promesonotal teeth short, usually pointed, projecting horizontally, not vertically. Propodeal teeth usually acute, shorter than the distance between the bases. Dorsal surface of the body moderately tuberculate, tuberculi small, tubercular setae short, recurved or straight and erect, tuberculi on sides of mesosoma minute, sometimes absent on sides of pronotum. Color medium reddish-brown.

HOLOTYPE WORKER: HL 0.81, HW 0.87, CI 107, SL 0.78, SI 90, ML 1.17. As in the diagnosis.. Integument of head coarse, sandpaperlike, with curved setae, posterior corners rounded. Dorsal and lateral margins of head tuberculate, largest tuberculi on posterior corners, smaller tuberculi on lateral margin. In full-face view, frontal carinae almost reach dorsal margin of head. In lateral view, preocular carinae form straight line traversing the antennal scrobe by 1/3 its width. Antennal scrobe shallow, not tuberculate, with some short setae in dorsal half of scrobe. Frontal lobes subtriangular with anterior side twice as long as posterior one. Mandibles shiny, striate with 7 teeth/denticles. Antennal scape with abundant appressed setae, surpassing dorsal margin of head by 1.5x its maximum diameter. Mesosomal teeth short and rounded, median pronotal teeth reduced. Each tooth bears several erect, curved setae. Dorsal surface of propodeum with two tuberculate ridges, leading to propodeal teeth; each ridge bearing three tuberculi and several recurved setae. Anterior peduncle of petiole short, less than 1/3 the length of petiolar node. Petiole half as wide as postpetiole. Postpetiole oval in dorsal view, wider than long; posterior margin concave. First gasteric tergite tuberculate with recurved setae; tuberculi small. Color uniformly medium reddish-brown, with a faint, dark stripe on first gastric tergite. Paratype workers: HL 0.75–0.95, HW 0.78–0.95, CI 97–103, SL 0.73–0.88, SI 89–100, ML 1.0–1.28.

Queen

Diagnosis from Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 0.95–1.05, HW 1.05–1.1, CI 105–111, SL 0.9, SI 82–86, ML 1.5–1.55. As in worker diagnosis, but with caste-specific morphology of the mesosoma related to wing bearing and the presence of small ocelli on the head. Dorsoventral pronotal teeth present only as right angles in dorsal view, rather than as a triangular tooth. Ventrolateral pronotal teeth small, broadly triangular. Mesoscutum with coarse longitudinal rugulae, tubercles absent, stiff, suberect setae moderately abundant, inclined posteriorly. First gastric tergite densely and minutely tuberculate, with abundant short, decumbent, slightly recurved setae.

PARATYPE QUEEN: HL 0.96, HW 0.99, CI 103, SL 0.84, SI 85, ML 1.47. As in worker and queen diagnosis, with caste specific structure of mesosomal morphology. Integument of head sandpaperlike, slightly irregular, fine-textured, dull with scattered minute tubercles. Head, tuberculation, frontal and preocular carinae, antennal scrobes and frontal lobes shaped as in worker. Mandibles shiny, striate with 9 teeth/denticles. Antennal scapes with many appressed setae, surpassing posterior corner of head 1x its maximum diameter. Mesosoma with typical morphology of the queen caste. In dorsal view, dorsolateral pronotal teeth short, broad, its peak almost forming a 90° angle, projecting horizontally not vertically. Posterior margin of scutellum slightly concave, edges do not form a distinct tooth. In lateral view, propodeal teeth very short and pointed, approximately 3⁄4 as long as broad at its base. Petiole, postpetiole, and gaster shaped as in workers.

Male

Diagnosis from Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 0.6–0.75. HW 0.6–0.75, CI 100–108, SL 0.6–0.8, SI 93–107, ML 1.3–1.65. Somewhat variable in size, but smaller than other North American Trachymyrmex males (ML 1.3–1.65). Dorsolateral pronotal teeth absent. Ventrolateral pronotal teeth small, triangular. Preocular carinae as described in the key. Posterior corners of head angulate in full-face view and bearing only small tuberculi.

PARATYPE MALE: HL 0.65, HW 0.7, CI 108, SL 0.65, SI 93, ML 1.3. Head broader than long, mandibles short, apical and subapical tooth present, other teeth small to minute, sometimes indistinct or partly to entirely absent. Preocular carinae weakening posteriorly, becoming less conspicuous, broken, or sometimes incomplete as it forms the posterior border of the antennal scrobe. Dorsal surface of head coarsely granulate, finely rugulose, posterior margin with less than 15 small tuberculi, no tooth present on the corners. Posterolateral pronotal teeth short, broadly pyramidal, sometimes rounded. Anterolateral pronotal teeth absent. Sculpture on mesosoma, petiole, postpetiole and gaster coarsely granulate. Fine rugulae present on most of the mesosoma, primarily longitudinal on the mesoscutum, mostly reticulate on the scutellum and on the sides. Rugulae and tuberculi largely absent from the first gastric tergite, but numerous short, appressed, recurved setae present. Head dark blackish brown, scape lighter brown, mandibles and funiculus yellowish brown.

Type Material

Holotype worker (SPC 6330) and the following paratypes: 15 workers, 1 queen [12-VIII- 2001, SPC 6330]; 13 workers [12-VIII-2001, SPC 6328]; 48 workers, 8 queens, 1 male [14-VIII-2001, UGM010814-01]; 34 workers [10-VIII-2005, CR050810-01]. Museum of Comparative Zoology, The Natural History Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, National Museum of Natural History, California Academy of Sciences, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, University of California, Davis and the private collections of Robert A. Johnson (Tempe, AZ, USA), William P. Mackay (El Paso, TX, USA) and Christian Rabeling (Austin, TX, USA). Examined (Rabeling et al. 2007).

Type Locality Information

U.S.A., Arizona: Cochise County, Chiricahua Mountains 0.5 km north of Southwestern Research Station. (Rabeling et al. 2007).

Etymology

In traditional Roman religion, Pomona was the goddess of fruit trees, gardens and orchards. Trachymyrmex pomonae therefore is Pomona’s Trachymyrmex, because the ant’s cultivation of fungus gardens is a highly developed form of “pomology” that would surely please the goddess. (Rabeling et al. 2007).

References

- Matthews, A.E., Rowan, C., Stone, C., Kellner, K., Seal, J.N. 2020. Development, characterization, and cross-amplification of polymorphic microsatellite markers for North American Trachymyrmex and Mycetomoellerius ants. BMC Research Notes 13, 173 (doi:10.1186/s13104-020-05015-3).

- Rabeling C, Cover SP, Mueller UG & Johnson RA. 2007. A review of the North American species of the fungus-gardening ant genus Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 1664:1-54.

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.