Trachymyrmex nogalensis

| Trachymyrmex nogalensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Trachymyrmex |

| Species: | T. nogalensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Trachymyrmex nogalensis Byars, 1951 | |

Trachymyrmex nogalensis is rarely collected and is also the only Trachymyrmex species in the US whose male remains undiscovered.

Identification

Trachymyrmex nogalensis is distinguished from other US Trachymyrmex species by the short, unique “scrobes” and the unusual basal lobe on the antennal scapes. In the field it can be confused only with the occasionally sympatric Trachymyrmex arizonensis, from which it is easily distinguished by the basal lobe on the antennal scape, (absent in T. arizonensis), and the distinctive frontal lobes of T. arizonensis, (absent in T. nogalensis). (Rabeling et al. 2007)

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Only known from two locations in Arizona: the type locality, Nogales (in Santa Cruz County) and the Chiricahua Mountains (Cochise County) in the southeast corner of the state (Rabeling et al. 2007).

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 32.12824° to 31.340378°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

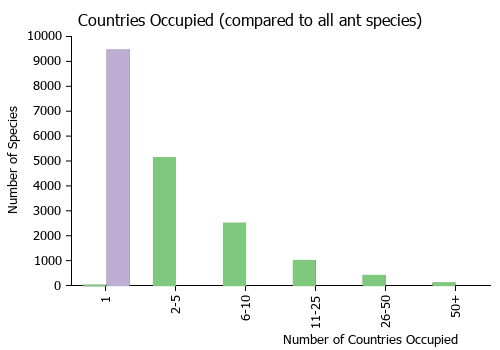

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

From Rabeling et al. (2007): All collections have been made in mid elevation habitats at 1200–1550 m. Byars (1951) collected workers and dealate queens on the porch of his house. Unfortunately, he provided no further information on the surrounding habitat or on any other nests. In the Chiricahua Mountains, we found T. nogalensis in creosote bush, mesquite-dominated desert habitats and on a rocky limestone outcrop dominated by Ocotillo, Acacia, Agave and Mimosa. Nests were cryptic and the entrances were located in cracks on rock-face. No information is available on nest architecture, fungus gardens, or number of workers in a colony because the extremely rocky ground makes excavation close to impossible. Trachymyrmex nogalensis is seldom encountered, probably because of it nocturnal foraging behavior and its cryptic nest sites. Studies of ecology, behavior and fungus cultivation would be fruitful areas for further research.

Castes

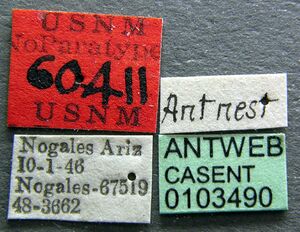

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Paratype of Trachymyrmex nogalensis. Worker. Specimen code casent0103490. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- nogalensis. Trachymyrmex nogalensis Byars, 1951: 109, figs. 1, 2 (w.) U.S.A. (Arizona).

- Type-material: holotype worker, paratype workers (number not stated, “numerous”), 2 paratype queens.

- Type-locality: holotype U.S.A.: Arizona, Nogales, 1.x.1946 (L.F. Byars); paratypes: workers with same data, 1 queen with same data but 10.vii.1947, 1 queen with same data but 5.viii.1948.

- Type-depositories: USNM (holotype); AMNH, MCZC, USNM (paratypes).

- Rabeling, et al. 2007: 13 (q.).

- Combination in Trachymyrmex: Solomon, Rabeling, et al. 2019: 948.

- Status as species: Smith, M.R. 1958c: 137; Hunt & Snelling, 1975: 22; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1411; Bolton, 1995b: 421; Rabeling, et al. 2007: 13 (redescription); Sánchez-Peña, et al. 2017: 87 (in key).

- Distribution: U.S.A.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Diagnosis from Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 1.1–1.35, HW 1.05–1.5, CI 96–112, SL 1.4–1.8, SI 117–133, ML 1.7–2.2. Large species (HL 1.1–1.35; HW 1.05–1.5), with relatively long legs and antennae (SI 117–133). Head generally longer than broad (CI 96–112), tapering slightly anterior to the eye, posterior border weakly concave. Antennal scape narrowing abruptly toward the antennal insertion, with a conspicuous lobe just distal to the narrowing. Frontal lobes well developed, evenly rounded, equilateral. Frontal carinae short, joining with preocular carinae to form short, distinctive “scrobes” that end just posterior to the level of the eye. Anterior terminus of the preocular carina forming a small tooth in full-face view. Anterolateral promesonotal teeth spinelike, sharply pointed, directed upwards and forward in side view. Propodeal spines toothlike, shorter than the distance between their bases. Body moderately tuberculate. Color yellowish brown.

Queen

Diagnosis from Rabeling et al. (2007): HL 1.36–1.45, HW 1.4–1.45, CI 97–104, SL 1.64–1.8, SI 117–124, ML 2.25–2.4. Generally as in worker diagnosis, but mesosoma with caste-specific morphology relating to wing-bearing and the head bearing small ocelli. Dorsolateral pronotal teeth large, tuberculate and sharply pointed in dorsal view; ventrolateral pronotal teeth well-developed, resembling a blunt lobe. Mesoscutum lacking longitudinal rugulae but with numerous small tubercles, each bearing a short, sharply recurved seta.

Male

Males are not known for this species.

Type Material

Holotype worker National Museum of Natural History. Examined (Rabeling et al. 2007).

Type Locality Information

Nogales, Arizona, U.S.A. (Rabeling et al. 2007).

Etymology

Trachymyrmex nogalensis was described from Nogales, Arizona, based on workers that Byars collected from a colony nesting under his house. The species name clearly refers to the type locality. (Rabeling et al. 2007)

References

- Byars, L. F. 1951. A new fungus-growing ant from Arizona. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 53: 109-111 (page 109, figs. 1, 2 worker described)

- Rabeling, C., S. P. Cover, R. A. Johnson, and U. G. Mueller. 2007. A review of the North American species of the fungus-gardening ant genus Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera : Formicidae). Zootaxa.1-53.

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Rabeling C., S. P. Cover, R. A. Johnson, and U. G. Mueller. 2007. A review of the North American species of the fungus-gardening ant genus Trachymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 1664: 1-53

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.