Mycetagroicus cerradensis

| Mycetagroicus cerradensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetagroicus |

| Species: | M. cerradensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetagroicus cerradensis Brandão & Mayhé-Nunes, 2001 | |

Combining in formation from labels and field notes of Kempf and Lenko, we can say that this species occurs in the “cerrado” (samples #4151, 4246, and 4472). Although we have no clear information on the collecting sites of most samples, all localities we listed above are (or were) cerrado areas. Lenko recorded nests as subterranean, with one circular entrance circled by a 3 mm sand crater, surrounded by a 5 cm high mound with 12 cm at base. He has also recorded the workers of sample #4472 carrying minute plant fragments and very small seeds of grasses and other unspecified items. The Botucatu sample label says “pasture.” (Brandao and Mayhe-Nunes 2001)

Identification

Brandao and Mayhe-Nunes (2001) - Mycetagroicus cerradensis is easily recognized by three features: the presence of two prominent clypeal concave projections, rounded at apex, the subtriangular frontal lobes, and the absence of median pronotal teeth.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: -15.78333333° to -24.1°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Brazil (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

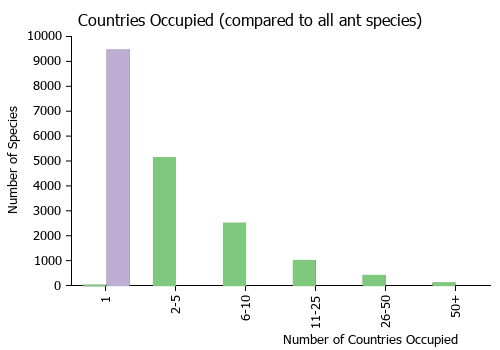

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Paratype of Mycetagroicus cerradensis. Worker. Specimen code casent0178478. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MZSP, Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103121. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

Phylogeny

| Mycetagroicus |

| ||||||||||||

Based on Micolino et al., 2020 (note Mycetagroicus urbanus not included).

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- cerradensis. Mycetagroicus cerradensis Brandão & Mayhé-Nunes, 2001: 644, figs. 1-7 (w.) BRAZIL.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

TL 3.36; HL 0.92: HW 0.92; IFW 0.52; ScL 0.78; TrL 1.34; Hfl 1.23. Uniformly brown-yellowish to medium brown: gaster darker than the rest of the body in the two Minas Gerais samples; the Paraopeba workers have also the frontal disk of the head darker than the rest of the body. Long and dense pilosity all over the body, hairs mostly erect, but flexuous, little shorter on the appendages than in other regions of the body.

Head. Dorsal surface of the mandibles with some 30 rugulae over a straight line perpendicular to the external margin at midlength, ending abruptly at the smooth flange parallel to the masticatory margin. Masticatory margin with an apical tooth followed by 7-10 minute regularly spaced teeth, except for the basal one which is separated from the others by a small diastema; the subapical teeth of similar size and triangular in young workers; external margin almost straight at base, weakly concave at apex, curving inwards at the level of the third subapical tooth. Clypeus with pronounced concave anterolateral projections with rounded apex, at each side, arising near the base of the frontal lobes. Frontal area triangular, depressed but mostly Inconspicuous. Frontal lobes subtriangular. the anterior border rounded, crenulated, and almost as long as the straight posterior borders: faces meeting in an attenuated angle of circa 120°. Frontal carinae sinuous, weakly diverging caudad, fading before reaching the occiput. Eyes with 12 facets across its greatest diameter. Antennal scapes surpassing the occipital corners by near one third of their length, when laid back over the head as much as possible. All funicular segments longer than broad.

Alitrunk. Lateral pranatal spines triangular when seen from above. projecting laterad when seen in frontal view. Pair of median projections on pronotum very short or absent; middle of the mesonotum with a low protuberance, better seen in side view, microscopically tuberculated. Anepisternum separated from katepisternum by a strong ridge. Metanotal groove relatively large in side view, shallowly impressed. Propodeal spiracle opening slit-shaped in side view.

Petiole, postpetiole, and gaster. Petiole without conspicuous projections: the node proper as seem from above slightly longer than broad, and broader anteriorly. Postpetiole slightly broader than long in dorsal view. Gaster with regularly spaced hair pits, almost in straight parallel lines. The dorsal disk of the gaster marked by two faint widely spaced longitudinal keels.

Type Material

Holotype: Worker, BRAZIL. sao Paulo State: Rancharla (22° 15' S, 50° 55' W). 5.x.1969, E. Amante (Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo # 6004 Kempfs notebook), deposited at MZSP. Paratypes (all from Brazil); 41 workers. same data as holotype (38 MZSP - one prepared for SEM: 3 National Museum of Natural History; 3 Centro de Pesquisas do Cacau); 4 workers, Distrito Federal: Brasilia (15° 47’ S, 47° 55' W), parque Nacional de Brasilia, 13-14.v.1971, “cerrado.” W. L. & D. E. Brown (col.) (2 MZSP: 2 Museum of Comparative Zoology): 33 workers, Golas: Faz. Cachoeirlnha, Jatal (17° 53' S, 51° 43' W), 20.vii.1964, Exp. Dep. Zool col. (MZSP # KL 4264) (20 MZSP; 3 California Academy of Sciences; 4 Instituto de Biologia Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro; 3 Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History; 3 USNM}: 3 workers, Mato Grosso (today Mato Grosso do Sul): Fazenda Fortaleza, Paranaiba (19° 40' S, 51° 11' W), 19.ii.1976. J. L. M. Diniz (Diniz's field book # 951) (MZSP): 3 workers, Minas Gerais: Paraopeba (19° 18' S, 44° 25' W), iii.1990, J. A. Barcelos (leg.) (2 MZSP; 1 CECL): 2 workers, Minas Gerais: Lassance (17° 54' S. 44° 34' W), 18.ix.1985, P. Pacheco col. (MZSP): 5 workers, Parana: Senges (21° 59' S, 48°23' W). 03.xi.1965, W. Kempf leg, (MZSP# 4154) (3 MZSP: 2 CECL); 19 workers, Sao Paulo: Fazenda Itaquere, Boa Esperanca do Sul (21° 59' S, 48° 23' W), 20.vii.1964, K. Lenko leg. (MZSP # 4472, Lenko notebook) (10 MZSP- one prepared for SEM: 3 CECL; 3 INPA; 3 The Natural History Museum): 6 workers, Sao Paulo: Agudos (22° 28' S, 49° 00' W), 13.xii.1955. W. Kempf leg. (MZSP # 1492: “Parque do Seminario” Kempf’s notebook) (4 MZSP; 2 CECL): 2 workers, Sao Paulo: Botucatu (22° 52' S. 48° 26' W), 11.iv.1985; 11.x.1984, M. F. Barros Pereira col (MZSP).

Etymology

The name refers to the distribution of this species, known only from the Brazilian “cerrados,” a savanna-like formation that once covered most of the Brazilian Central Plateau.

References

- Brandão, C. R. F.; Mayhé-Nunes, A. J. 2001. A new fungus-growing ant genus, Mycetagroicus gen. n., with the description of three new species and comments on the monophyly of the Attini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 38(3B): 639-665. (page 644, figs. 1-7 worker described)

- Solomon, S.E.; Lopes, C.T.; Mueller, U.G.; Rodrigues, A.; Sosa-Calvo, J.; Schultz, T.R.; Vasconcelos, H.L. 2011. Nesting biology and fungiculture of the fungus-growing ant, Mycetagroicus cerradensis: New light on the origin of higher attine agriculture. Journal of Insect Science: Vol. 11: Article 12: 1-14.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Brandão C. R. F., and A. J. Mayhé-Nunes. 2001. A new fungus-growing ant genus, Mycetoagroicus gen. n., with the description of three new species and comments on the monophyly of the Attini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 38: 639-665.

- Brandão, C.R.F. and Mayhe-Nunes. 2008. Uma nova espécie de formiga cultivadora de fungo, do gênero Mycetagroicus Brandão & Mayhé-Nunes (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Attini). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 52(3)

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Ramos L. S., R. Z. B. Filho, J. H. C. Delabie, S. Lacau, M. F. S. dos Santos, I. C. do Nascimento, and C. G. S. Marinho. 2003. Ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the leaf-litter in cerrado stricto sensu areas in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Lundiana 4(2): 95-102.

- Solomon S. E., C. Rabeling, J. Sosa-Calvo, C. Lopes, A. Rodrigues, H. L. Vasconcelos, M. Bacci, U. G. Mueller, and T. R. Schultz. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939–956.

- Solomon S., C. T. Lopes, U. G. Mueller, A. Rodrigues, J. Soza-Calvo, T. R. Schultz, and H. L. Vasconcelos. 2011 . Nesting biology and fungiculture of the fungus-growing ant Mycetagroicus cerradensis: New light on the origin of higher-attine agriculture. Journal of Insect Science 11: 11:12.

- Vasconcelos H. L., B. B. Araujo, A. J. Mayhé-Nunes. 2008. Patterns of diversity and abundance of fungus-growing ants (Formicidae: Attini) in areas of the Brazilian Cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 25(3): 445-450.