Cyphomyrmex flavidus

| Cyphomyrmex flavidus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Cyphomyrmex |

| Species: | C. flavidus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyphomyrmex flavidus Pergande, 1896 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Collected in Mexico nesting under rocks.

Identification

Wheeler (1907) - at first sight closely resembles Cyphomyrmex wheeleri. It may be distinguished, however, by the absence of teeth on the petiole, the much broader and more truncated ear-like corners of the head, longer antennal scapes and much blunter ridges and projections on the thorax. C. flavidus is thus intermediate in several respects between wheeleri and Cyphomyrmex rimosus, but is undoubtedly a distinct species.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 33.71888889° to -14.79861111°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States.

Neotropical Region: French Guiana, Mexico (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Kempf (1966) reported the following about the synonymized dentatus:

According to Wheeler (1901: 200-1), who first collected this species on December 26 (year not given), the species is "not uncommon along the barrancas where it nests under stones, forming irregular chambers about the roots of the grasses. There are sometimes two queens in a nest. The older and darker queens and workers have the head and thorax covered with a bluish bloom. C. rimosus (Wheeler obviously refers to the present form which he considered as a mere race of rimosus! W. W. K.) is said not to cultivate mushroom gardens, but this is scarcely correct. They certainly collect caterpillar excrement and on this they grow a peculiar fungus which is not in the form of a white mycelium, like that cultivated by some other species of Cyphomyrmex (C. wheeleri Forel, for example) but consisting of clusters of small orange yellow, spherical or pyriform nodules about 5 mill. (= 0.5 mm?) in diameter. The exhausted masses of caterpillar excreta are piled on the refuse heap in a distant corner of the nest. The eggs of C. rimosus (again the present form is meant! W. W. K.) are very broad and short, almost spherical".

Dr. Skwarra (1934: 131) rediscovered the same species at Cuernavaca, finding two earth nests, one of them in the loosely heaped up refuse of Atta nests. She surmises that dentatus possibly uses this material as substrate for its own fungus.

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code castype00657. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code castype00658. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

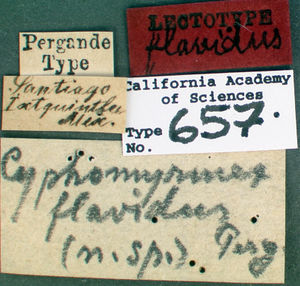

- flavidus. Cyphomyrmex flavidus Pergande, 1896: 895 (w.) MEXICO (Nayarit).

- Type-material: lectotype worker (by designation of Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 485), 2 paralectotype workers.

- [Notes (i): the taxon was based originally on 7 syntype workers; (ii) Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 485, cite 3w syntypes USNM; (iii) the remaining four could not be found by Snelling & Longino, but they suspect one may be in AMNH.]

- Type-locality: lectotype Mexico: Tepic, Santiago Ixtquintla, x.-xi.1894 (G. Eisen & Vaslit); paralectotypes with same data.

- Type-depositories: USNM (lectotype); LACM, USNM (paralectotypes).

- Status as species: Forel, 1899c: 41; Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 726 (redescription); Emery, 1924d: 341; Weber, 1940a: 409 (in key); Kempf, 1966: 172 (redescription); Weber, 1966: 167; Kempf, 1972a: 92; Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 485; Bolton, 1995b: 167; Ward, 2005: 65; Fernández & Serna, 2019: 850.

- Senior synonym of dentatus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 485; Bolton, 1995b: 167.

- Distribution: Colombia, Mexico, U.S.A.

- dentatus. Cyphomyrmex rimosus r. dentatus Forel, 1901c: 124 (w.) MEXICO (Morelos).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- [Note: Kempf, 1966: 184, cites 5w syntypes MCZC.]

- Type-locality: Mexico: Morelos, Cuernavaca (W.M. Wheeler).

- Type-depositories: MHNG, MCZC.

- Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 723 (q.).

- Subspecies of rimosus: Wheeler, W.M. 1907c: 722; Emery, 1924d: 342; Weber, 1940a: 412 (in key).

- Status as species: Kempf, 1966: 184 (redescription); Kempf, 1972a: 92.

- Junior synonym of flavidus: Snelling, R.R. & Longino, 1992: 485; Bolton, 1995b: 167.

Description

Worker

Wheeler (1907) - Length: 2.2-2.8 mm.

Head, without the mandibles, longer than broad, broader behind than in front, with obtusely excised posterior border and prominent posterior corners. Eyes convex, at the middle of the head. Mandibles small and acute, with oblique, apparently 5-toothed blades. Clypeus long and rather flat, with a minute median excision in its thin anterior border. Frontal area triangular. Lobes of frontal carina very large, horizontal, half as long as the head and extending out laterally a little beyond the borders of the head. Posteriorly each of these lobes has a deep subtriangular depression in its surface. The ridges of the frontal carina diverge backward to the posterior corners where they pass over into the postorbital carina, not through a rounded arc but rectangularly, so that the termination of the antennal groove is broad and truncated. There is a ridge on each side of the inferior occipital portion of the head and a pair of projections on the vertex, which are continued laterally along the occipital border as a pair of blunt ridges to the posterior corners. Antennal scapes enlarged towards the tips, which extend a little beyond the posterior corners; joints 2-7 of the funiculus a little broader than long. Thorax robust; pronotum with a pair of acute inferior teeth, which are directed forward, and a blunt protuberance on each side above', Mesonotum in the form of an elevated, elliptical and slightly concave disc, bordered with a low ridge which is interrupted in the middle behind and in the middle on each side. This ridge bears a pair of rounded swellings just in front of its lateral interruptions. Mesoepinotal constriction deep and narrow. Epinotum with a pair of swellings at its base; declivity sloping, longer than the base; spines reduced to a pair of laterally compressed and rather acute teeth which are as long as they are broad at the base. Petiole and post petiole resembling each other in shape; the former twice as broad as long, broader behind where its sides are produced as a pair of blunt angles; it is flattened above, without spines or teeth and with a small semicircular impression in the middle of its posterior border. Postpetiole broader than the petiole, more than twice as broad as long, rounded in front, with a median groove, broadening behind; posterior margin with three semicircular impressions of which the median is the largest. Gaster longer than broad, suboblong, with straight, feebly marginate sides, rounded anterior and posterior borders, and a short median groove at the base of the first segment. Hind femora curved, with an angular, compressed projection near the base on the flexor side. Opaque throughout, very finely and densely punctate-granular.

Hairs minute, appressed, slightly dilated, glistening white, rather sparse and indistinct. Pubescence fine, whitish, confined to the antennal funiculi.

Ferruginous yellow; clypeus, frontal lobes, front and middle of vertex more or less brownish; mandibular teeth black.

Queen

Wheeler (1907) describing the synonymized dentatus:

Two dealated females of dentatus in my collection measure 2.4 mm. in length, and have prominent but blunt and upturned prothoracic spines and strong laterally compressed epinotal teeth; the epinotal declivity is very concave, the postero-lateral cones of the postpetiole are more prominent and the median dorsal region of the same segment is more concave than in the worker. The head and thorax are much rougher than in the females of the typical rimosus and the gaster is more strongly tubercular, with a short but deep median depression at the base of the first segment. The body is dark brown, the upper surface of the head and thorax blackish and covered with a bluish bloom.

Type Material

Kempf (1966) - Workers collected by Eisen and Vaslit at Tepic and Santiago Ixcuintla in Nayarit State, Mexico; presumably deposited in the U.S. National Museum. No specimens seen.

References

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Kempf, W. W. 1966 [1965]. A revision of the Neotropical fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex Mayr. Part II: Group of rimosus (Spinola) (Hym., Formicidae). Stud. Entomol. 8: 161-200 (page 172, see also)

- Pergande, T. 1896. Mexican Formicidae. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. (2) 5: 858-896 (page 895, worker described)

- Skwarra, E. 1934. Ökologische Studien über Ameisen und Ameisenpflanzen in Mexiko. 153 p. Printer: R. Leupold, Königsberg.

- Snelling, R. R.; Longino, J. T. 1992. Revisionary notes on the fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex, rimosus group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Attini). Pp. 479-494 in: Quintero, D., Aiello, A. (eds.) Insects of Panama and Mesoamerica: selected stu (page 485, Senior synonym of dentatus)

- Varela-Hernández, F., Medel-Zosayas, B., Martínez-Luque, E.O., Jones, R.W., De la Mora, A. 2020. Biodiversity in central Mexico: Assessment of ants in a convergent region. Southwestern Entomologist 454: 673-686.

- Wheeler, W. M. 1901. Notices biologiques sur les fourmis Mexicaines. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 45:199-205.

- Wheeler, W. M. 1907d. The fungus-growing ants of North America. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 23: 669-807 (page 726, see also)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Cancino, E.R., D.R. Kasparan, J.M.A. Coronado Blanco, S.N. Myartseva, V.A. Trjapitzin, S.G. Hernandez Aguilar and J. Garcia Jimenez. 2010. Himenópteros de la Reserva El Cielo, Tamaulipas, México. Dugesiana 17(1):53-71

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- Groc S., J. H. C. Delabie, F. Fernandez, M. Leponce, J. Orivel, R. Silvestre, Heraldo L. Vasconcelos, and A. Dejean. 2013. Leaf-litter ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a pristine Guianese rainforest: stable functional structure versus high species turnover. Myrmecological News 19: 43-51.

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Klingenberg, C. and C.R.F. Brandao. 2005. The type specimens of fungus growing ants, Attini (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae) deposited in the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil. Papeis Avulsos de Zoologia 45(4):41-50

- Pergande, T. 1895. Mexican Formicidae. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences Ser. 2 :850-896

- Snelling R. R., and J. T. Longino. 1992. Revisionary notes on the fungus-growing ants of the genus Cyphomyrmex, rimosus group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Attini). Pp. 479-494 in: Quintero, D.; Aiello, A. (eds.) 1992. Insects of Panama and Mesoamerica: selected studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, xxii + 692 pp.

- Vasquez-Bolanos M. 2011. Checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Mexico. Dugesiana 18(1): 95-133.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133