Nylanderia fulva

| Nylanderia fulva | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Lasiini |

| Genus: | Nylanderia |

| Species: | N. fulva |

| Binomial name | |

| Nylanderia fulva (Mayr, 1862) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Tawny Crazy Ant | |

| Language: | English |

Kumar et al. (2015) - The tawny crazy ant, Nylanderia fulva is invading the southern United States (Gotzek et al. 2012). Its occurrence in the United States (US) was first documented in Houston in 2002 (Meyers and Gold 2008). It may have arrived in Florida earlier (Klotz et al. 1995; Deyrup et al. 2000), but collections of the very similar Nylanderia pubens from Florida dating back to the 1950s (Trager 1984) prevent an accurate identification of early pest populations. At present, this species occurs in Texas, Florida, southern Mississippi (MacGown and Layton 2010) and southern Louisiana (Hooper-Bui et al. 2010; Fig. 1). Introduction of N. fulva in Colombia caused extensive ecological and agricultural damage (Zenner de Polania 1990). In the Southern United States, N. fulva displaces red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta), and regionally distributed native species, thereby reducing both biological and functional diversity (LeBrun et al. 2013). Nylanderia fulva can also transport pathogens of plants, humans, and other animals (McDonald 2012). Nests within populations contain multiple queens (Zenner de Polania 1990). Interconnected nests of these ants form extraordinarily dense populations that greatly exceed the combined densities of all ants in adjacent uninvaded assemblages (LeBrun et al. 2013). They feed on small insects and vertebrates, and honeydew secreted by aphids (Zenner de Polania and Bola~nos 1985). They invade people’s homes, nest in crawl spaces and walls, and damage electrical equipment resulting in millions of dollars of losses (Blackwell 2014). Populations spread about 200 m per year as a result of nest fission at the invasion front (Meyers and Gold 2008). Female reproductives of N. fulva have not been observed to engage in alate flights, so long-distance dispersal occurs largely as a result of human transport of nesting ants.

| At a Glance | • Invasive • Supercolonies |

Identification

Males are needed for species determinations. See Nylanderia pubens.

Identification Keys including this Taxon

Distribution

Known from numerous locations throughout the neotropics, and beyond, but identification of this and similar Nylanderia suggest published accounts about this species are potentially suspect.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 25.68015° to -34.833°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States.

Neotropical Region: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil (type locality), Chile, Colombia, Cuba (type locality), Dominican Republic, Ecuador, French Guiana, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Mexico, Paraguay, Suriname, Uruguay.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

The following text and map are from Gotzek et al. (2012). References that were indicated but removed from the text are stated in the original publication:

There has been widespread misidentification of Nylanderia fulva. Within museum collections, misidentifications are common given the morphological similarities of the workers within the genus overall, as well as because of uncertainties regarding species boundaries.

Using a number of determination methods, it has been shown that this is the species that has experienced a population explosion in and around Houston, Texas that began in 2002 (Rasberry Ant).

Since its detection in Harris County, Texas, the new invasive has rapidly expanded its range and is now found in 21 counties in southeast Texas and has recently been discovered from southwestern Mississippi and Louisiana (see Figure).

Figure 1. Reported distribution of the Rasberry Crazy Ant in the United States (in blue). The distribution of Nylanderia cf. pubens in Florida is given in orange, but we suspect that these may prove to be N. fulva. Counties highlighted with solid colors indicate verified occurrences, whereas hatched counties are unconfirmed reports. Red dots indicate collection sites for samples used in this study. The actual distribution of N. fulva in the United States is most likely to be more widespread. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0045314.g001

Given the uncertainty of workerbased identifications of N. fulva and N. pubens most publications that involve either of these species are suspect; they may not involve the species listed in the publication, including the possibility that they are neither N. fulva nor N. pubens and are an entirely different Nylanderia species. It appears at this time that N. pubens is restricted to the Caribbean region. This species has been reported to be relatively to be relatively common in southern Florida in the 1950’s –1970’s, where it was also most recently found in 1994 (M. Deyrup, pers. comm. to JSL). It is not known whether these populations still persist today. Since we show that samples from northern Florida initially considered to be N. cf. pubens are actually N. fulva and given the invasive nature of N. fulva, we hypothesize that most or even all alleged occurrences of N. pubens in Florida are misidentified N. fulva. This would not be surprising, since the distribution is solely based on worker identifications (D. Oi, pers. comm. to DG). We also suspect that N. pubens may not have good invasive capabilities compared to N. fulva, given the currently rapidly expanding distribution of N. fulva in the United States and lack of N. pubens in our samples from northern Florida. It will require much better sampling of molecular data or male samples from throughout Florida to test our hypothesis. Currently, the Caribbean is likely the only place where N. fulva and N. pubens are sympatric and therefore the only region where identifications of workers will be difficult. If we are correct concerning the distribution and inability of N. pubens to become a pest, then the population explosions attributed to N. pubens that plagued the Caribbean from 19th century Bermuda to the recent outbreak on St. Croix and in southern Florida may very well have been N. fulva instead of N. pubens. Nylanderia fulva is known to be an invasive ant, most recently from Colombia where an outbreak occurred after this species was apparently introduced to control leafcutter ants and venomous snakes.

Therefore outbreaks may be common in N. fulva and should be expected in all inhabited areas, at least in the putative invasive part of its range. The current reported distribution of N. fulva in the United States is still patchy, but the pattern suggests that it will be able to invade the entire Gulf Coast, if it has not already done so. To accurately predict its potential range will require more detailed descriptions of its ecology, natural history, and distribution in its native range which can then be used to inform predictive environmental niche modeling. However, the native range of N. fulva must first be identified and, ideally, the source population(s) of the invasive populations must also be known. While this information is still lacking, it is highly likely that N. fulva is native to South America, probably southern South America (the type locality is in Brazil). Like other notorious invasive ants, e.g., Solenopsis invicta or Linepithema humile, it is possible that N. fulva could be yet another ant from the greater Parana drainage that has become invasive elsewhere. Detailed phylogeographic and population genetic studies based on broad and extensive sampling across the entire range of the species will help address these issues and provide the basis for effective management of N. fulva in North America, for example through the introduction of co-evolved biological control agents.

Research can now focus on this species’ population dynamics, ecology, natural history, and identification of its native range to better understand the causes and consequences of such rapid population growth. This endeavor would not have been possible without the collection-based resources and taxonomic expertise present in natural history museums, underscoring their value for both basic and applied research.

Eyer et al. (2018) highlighted a shift in colony structure following invasion. In its native range, colonies are separated from one another, whereas no boundaries between nests are found in its invasive range. This genetic result is confirmed by a lack of aggression towards conspecifics. This suggests that N. fulva forms a single supercolony spreading more than 2000km covering its entire invasive range. This social structure provides several advantages in terms of colony growth, density, productivity and survival, and favors its invasive success outcompeting native species through resource monopolization. Drastic genetic differences between males and females might stem from a distortion of segregation, with queens preferentially transmitted paternal alleles to their sons and maternal ones to their daughters. As a consequence, the sexually produced female castes are highly heterozygous as they always inherited different alleles from their mother and father. This strategy allows N. fulva to maintain heterozygosity and overcomes the depletion of genetic diversity resulting from the founder event.

Regional Information

Brazil

DaRocha et al. (2015) studied the diversity of ants found in bromeliads of a single large tree of Erythrina, a common cocoa shade tree, at an agricultural research center in Ilhéus, Brazil. Forty-seven species of ants were found in 36 of 52 the bromeliads examined. Bromeliads with suspended soil and those that were larger had higher ant diversity. Nylanderia fulva was found in 18 different bromeliads but was associated with twigs and bark cavities, rather than suspended soil or litter, of the plants.

Chemical Ecology

LeBrun et al. (2015) found a behaviour, first noted and resulting from interactions between Solenopsis invicta and N. fulva, that detoxifies fire ant venom is expressed widely across ants in the subfamily Formicinae:

Solenopsis invicta is one of twenty exclusively New World fire ants, a subgroup of species within the large genus Solenopsis characterized by large, aggressive colonies of polymorphic workers with piperidine alkaloid-based venom (Blum 1992). Nylanderia fulva detoxifies S. invicta venom by applying its own venom, formic acid, to body parts exposed to S. invicta venom, using a prescribed series of stereotyped actions, or acidopore grooming. Standing on its hind and middle legs, the worker curls its gaster underneath its body. It then touches its acidopore (specialized exocrine-gland duct located at the gaster tip, uniquely shared among formicines) to its mandibles, runs its front legs through its mandibles, and grooms itself vigorously by rubbing its legs over its body, periodically reapplying its acidopore to its mandibles. Acidopore grooming by N. fulva results in greatly increased survivorship following conflict with fire ants or artificial exposure to fire ant venom (LeBrun et al. 2014). Although it is not yet demonstrated how formic acid alters the bioactivity of fire ant venom, formic acid protonates the nitrogen in fire ant venom alkaloids forming a protic ionic liquid with distinct physical properties (Chen et al. 2014). Among changes to the venom including the denaturation of associated venom enzymes and an increase in viscosity, the formate salt of the alkaloid is more polar and less lipophilic, which may reduce the ability of the protonated alkaloid to penetrate the waxy cuticle or cell membranes (Meinwald 2014). In addition to fire ant venom detoxification, the toxicity of formic acid itself is reduced as a result of salt formation. Acidopore grooming provides an effective mechanism for detoxification because, in conflicts with other ants, fire ants primarily apply venom topically by gaster flagging (a venom dispersal behavior) and smearing or flicking venom droplets exuded on the tips of their stingers onto competitors (Obin and Vandermeer 1985).

The specific chemistry of the reaction of formic acid with venom alkaloids and its use when challenged with specific venom types indicates that alkaloid venoms are targets of detoxification grooming. Solenopsis thief ants, and Monomorium species stand out as brood-predators of formicine ants that produce piperidine, pyrrolidine, and pyrroline venom, providing an important ecological context for the use of detoxification behavior. Detoxification behavior also represents a mechanism that can influence the order of assemblage dominance hierarchies surrounding food competition. Thus, this behavior likely influences ant-assemblages through a variety of ecological pathways.

Zhang et al (2015) discovered the interaction of Dufour’s gland secretion and formic acid from the venom gland was a potent recruitment communication in Nylanderia fulva. They suggested "Such recruitment via airborne volatiles from two separate glands is evidently an efficient mechanism enhancing both cooperative exploitation of large food items and the ability to marshal mass attack against enemies. This type of synergistic recruitment may also explain why N. fulva workers sometimes accumulate in massive numbers in electrical equipment. The initial response to outdoor electrical devices may simply be due to warmth, but short circuiting could create a snowball effect, whereby electrical and physical stimulation leads to ever more Dufour’s gland and venom gland discharge resulting in a much more dramatic response."

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Diptera

This species is a host for the phorid fly Pseudacteon convexicauda (a parasite) in Argentina (Sanchez-Restrepo et al., 2020).

Endoparasites

Plowes et al. (2015) discovered the microsporidian fungus Myrmecomorba nylanderiae in adult N. fulva.

Hemiptera

This species is associated with the aphids Aphis craccivora, Aphis vernoniae, Chaitophorus viminicola, Cinara juniperivora, Sanbornia juniperi and Shivaphis celti (Saddiqui et al., 2019 and included references).

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0173491. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ALWC, Alex L. Wild Collection. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

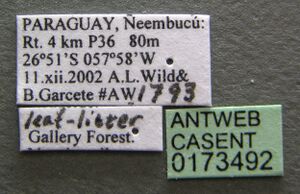

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0173492. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ALWC, Alex L. Wild Collection. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- fulva. Prenolepis fulva Mayr, 1862: 698 (w.q.) BRAZIL. Forel, 1891b: 94 (m.); Forel, 1912i: 67 (m.). Combination in Pr. (Nylanderia): Forel, 1908b: 67; in Paratrechina (Nylanderia): Emery, 1925b: 222; in Nylanderia: Kempf, 1972a: 166; in Paratrechina: Snelling, R.R. & Hunt, 1976: 122; in Nylanderia: LaPolla, Brady & Shattuck, 2010a: 127. Senior synonym of fumata: Wild, 2007b: 45. See also: Fernández, 2000: 146; Fox, et al. 2010: 795. Current subspecies: nominal plus biolleyi, fumatipennis, incisa, longiscapa, nesiotis. Senior synonym of cubana: LaPolla & Kallal, 2019: 405.

- cubana. Paratrechina (Nylanderia) fulva st. cubana Santschi, 1930e: 81 (w.) CUBA.

- Combination in Nylanderia: Kempf, 1972a: 167.

- Combination in Paratrechina: Brandão, 1991: 366.

- Combinaiton in Nylanderia: LaPolla, Brady & Shattuck, 2010a: 127.

- Junior synonym of fulva: LaPolla & Kallal, 2019: 405.

- fumata. Prenolepis fulva var. fumata Forel, 1909a: 264 (w.) PARAGUAY. Forel, 1912i: 67 (q.). Combination in Pr. (Nylanderia): Forel, 1913l: 246; in Paratrechina (Nylanderia): Emery, 1925b: 222; in Nylanderia: Kempf, 1972a: 166; in Paratrechina: Brandão, 1991: 366; in Nylanderia: LaPolla, Brady & Shattuck, 2010a: 127. Junior synonym of fulva: Wild, 2007b: 45.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Lange: 3.1 – 3.5mm. Gelbbraun, glanzend, Mandibeln, Geissel, Beine und besonders die Gelenke der Beine und die Tarsen heller. Mandibeln langsgestreift. Clypeus fast glatt, vorne nicht ausgerandet. Kopf seicht und zerstreut runzlig punctirt. Thorax fein runzlig punctirt , ebenso der Hinterleib, Scheibe des ersteren fast glatt. Schuppe oben abgerundet.

Queen

Lange: 6mm. Rothbraun, Gelenke der Beine und Tarsen gelb. Anliegende Pubescenz am Hinterleibe reichlich. Clypeus glanzend, fast glatt. Kopf, Thorax und Hinterleib fein runzlig punctirt. Schuppe oben ausgerandet.

Type Material

Rio Janeiro (Novara).

References

- Albuquerque, E., Prado, L., Andrade-Silva, J., Siqueira, E., Sampaio, K., Alves, D., Brandão, C., Andrade, P., Feitosa, R., Koch, E., Delabie, J., Fernandes, I., Baccaro, F., Souza, J., Almeida, R., Silva, R. 2021. Ants of the State of Pará, Brazil: a historical and comprehensive dataset of a key biodiversity hotspot in the Amazon Basin. Zootaxa 5001, 1–83 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5001.1.1).

- Baena, M.L., Escobar, F., Valenzuela, J.E. 2019. Diversity snapshot of green–gray space ants in two Mexican cities. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science 40, 239–250 (doi:10.1007/s42690-019-00073-y).

- Baty, J.W., Bulgarella, M., Dobelmann, J., Felden, A., Lester, P.J. 2020. Viruses and their effects in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 30: 213-228 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_030:213).

- Boudinot, B.E., Borowiec, M.L., Prebus, M.M. 2022. Phylogeny, evolution, and classification of the ant genus Lasius, the tribe Lasiini and the subfamily Formicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Systematic Entomology 47, 113-151 (doi:10.1111/syen.12522).

- Conceição-Neto, R., França, E.C.B., Feitosa, R.M., Queiroz, J.M. 2021. Revisiting the ideas of trees as templates and the competition paradigm in pairwise analyses of ground-dwelling ant species occurrences in a tropical forest. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 65, e20200026 (doi:10.1590/1806-9665-rbent-2020-0026).

- DaRocha, W. D., S. P. Ribeiro, F. S. Neves, G. W. Fernandes, M. Leponce, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2015. How does bromeliad distribution structure the arboreal ant assemblage (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on a single tree in a Brazilian Atlantic forest agroecosystem? Myrmecological News. 21:83-92.

- Dekoninck, W., Wauters, N., Delsinne, T. 2019. Capitulo 35. Hormigas invasoras en Colombia. Hormigas de Colombia.

- Dröse, W., Podgaiski, L.R., Gossner, M.M., Meyer, S.T., Hermann, J.-M., Leidinger, J., Koch, C., Kollmann, J., Weisser, W.W., de S. Mendonça, M., Overbeck, G.E. 2021. Passive restoration of subtropical grasslands leads to incomplete recovery of ant communities in early successional stages. Biological Conservation 264, 109387 (doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109387).

- Eduardo Gonçalves Paterson Fox, Daniel Russ Solis, Mônica Lanzoni Rossi & Odair Correa Bueno. 2010. Morphological studies on the mature worker larvae of Paratrechina fulva (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Sociobiology, 55, 795-803.

- Emery, C. 1925d. Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Formicinae. Genera Insectorum 183: 1-302 (page 222, Combination in Paratrechina (Nylanderia))

- Eyer, P.-A., Blumenfeld, A.J., Vargo, E.L. 2019. Sexually antagonistic selection promotes genetic divergence between males and females in an ant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 24157–24163 (doi:10.1073/PNAS.1906568116).

- Eyer, P.-A., McDowell, B., Johnson, L.N.L., Calcaterra, L.A., Fernandez, M.B., Shoemaker, D., Puckett, R.T. & Vargo, E.L. 2018. Supercolonial structure of invasive populations of the tawny crazy ant Nylanderia fulva in the US. BMC Evolutionary Biology 18, 209 (DOI 10.1186/s12862-018-1336-5).

- Fernández, F. 2000a. Formis99: literatura sobre las hormigas del mundo. Biota Colomb. 1: 132-134 (page 146, see also)

- Fernández, F. 2000b. Notas taxonómicas sobre la "hormiga loca" (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Paratrechina fulva) en Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 26: 145-149 (see also)

- Fernandez, F., Guerrero, R.J., Sánchez-Restrepo, A.F. 2021. Sistemática y diversidad de las hormigas neotropicales. Revista Colombiana de Entomología 47, 1–20 (doi:10.25100/socolen.v47i1.11082).

- Fontenla, J.L., Brito, Y.M. 2011. Hormigas invasoras y vagabundas de Cuba. Fitosanidad 15(4), 253-259.

- Forel, A. 1891c. Les Formicides. [part]. In: Grandidier, A. Histoire physique, naturelle, et politique de Madagascar. Volume XX. Histoire naturelle des Hyménoptères. Deuxième partie (28e fascicule). Paris: Hachette et Cie, v + 237 pp. (page 94, male described)

- Forel, A. 1908c. Fourmis de Costa-Rica récoltées par M. Paul Biolley. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 44: 35-72 (page 67, Combination in Pr. (Nylanderia))

- Forel, A. 1912j. Formicides néotropiques. Part VI. 5me sous-famille Camponotinae Forel. Mém. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 20: 59-92 (page 67, male described)

- Fox, E.G.P., Solis, D.R., Rossi, M.L. & Bueno, O.C. 2010. Morphological studies on the mature worker larvae of Paratrechina fulva (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Sociobiology 55, 795-804.

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Gochnour, B.M., Suiter, D.R., Booher, D. 2019. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) fauna of the Marine Port of Savannah, Garden City, Georgia (USA). Journal of Entomological Science 54, 417-429 (doi:10.18474/jes18-132).

- Gotzek, D., S. G. Brady, R. J. Kallal, and J. S. LaPolla. 2012. The Importance of Using Multiple Approaches for Identifying Emerging Invasive Species: The Case of the Rasberry Crazy Ant in the United States. PLoS ONE. 7:e45314. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0045314

- Hill, J.G. 2015. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Big Thicket Region of Texas. Midsouth Entomologist 8: 24-34.

- Hornfeldt, J.A., Ohyama, L., Lucky, A. 2020. Using behavioral experimentation to understand the social structure of the Little Fire Ant (Wasmannia auropunctata) in Florida. University of Florida Journal of Undergraduate Research 22: 1-9.

- Kallal, R.J. & LaPolla, J.S. 2012. Monograph of Nylanderia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the World, Part II: Nylanderia in the Nearctic. Zootaxa 3508, 1-64.

- Kempf, W. W. 1972b. Catálogo abreviado das formigas da regia~o Neotropical. Stud. Entomol. 15: 3-344 (page 166, Combination in Nylanderia)

- Koch, E.B.de A., Marques, T.E.D., Mariano, C.S.F., Neto, E.A.S., Arnhold, A., Peronti, A.L.B.G., Delabie, J.H.C. 2020. Diversity and structure preferences for ant-hemipteran mutualisms in cocoa trees (Theobroma cacao L., Sterculiaceae). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi - Ciências Naturais 15, 65–81 (doi:10.46357/bcnaturais.v15i1.251).

- Kumar, S., E. G. LeBrun, T. J. Stohlgren, J. A. Stabach, D. L. McDonald, D. H. Oi, and J. S. LaPolla. 2015. Evidence of niche shift and global invasion potential of the Tawny Crazy ant, Nylanderia fulva. Ecology and Evolution. 5:4628-4641. doi:10.1002/ece3.1737

- LaPolla, J.S., Kallal, R.J. 2019. Nylanderia of the World Part III: Nylanderia in the West Indies. Zootaxa 4658 (3): 401–451 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4658.3.1).

- Lawson, K.J., Oi, D.H. 2020. Minimal intraspecific aggression among Tawny Crazy Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Florida. Florida Entomologist 103, 247-252 (doi:10.1653/024.103.0215).

- LeBrun, E. G., P. J. Diebold, M. R. Orr, and L. E. Gilbert. 2015. Widespread Chemical Detoxification of Alkaloid Venom by Formicine Ants. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 41:884-895. doi:10.1007/s10886-015-0625-3

- LeBrun, E.G., Plowes, R.M., Folgarait, P.J., Bollazzi, M., Gilbert, L.E. 2019. Ritualized aggressive behavior reveals distinct social structures in native and introduced range tawny crazy ants. PLOS ONE 14, e0225597 (doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0225597).

- Lubertazzi, D. 2019. The ants of Hispaniola. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 162(2), 59-210 (doi:10.3099/mcz-43.1).

- Lutinski, J., de Filtro, M., Baucke, L., Dorneles, F., Lutinski, C., Guarda, C. 2021. Ant assemblages (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from areas under the direct influence of two small hydropower plants in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Environmental Sciences (Online), 1-9 (doi:10.5327/Z217694781030).

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Mayr, G. 1862. Myrmecologische Studien. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 12: 649-776 (page 698, worker, queen described)

- Melo, T.S., Koch, E.B.A., Andrade, A.R.S., Travassos, M.L.O., Peres, M.C.L., Delabie, J.H.C. 2021. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in different green areas in the metropolitan region of Salvador, Bahia state, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology 82, e236269 (doi:10.1590/1519-6984.236269).

- Moss, A.D., Swallow, J.G., Greene, M.J. 2022. Always under foot: Tetramorium immigrans (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a review. Myrmecological News 32: 75-92 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_032:075).

- Oi, D. 2020. Seasonal prevalence of queens and males in colonies of Tawny Crazy Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Florida. Florida Entomologist 103: 415-417 (doi:10.1653/024.103.0318).

- Plowes, R.M., Becnel, J.J., LeBrun, E.G., Oi, D.H., Valles, S.M., Jones, N.T. & Gilbert, L.E. 2015. Myrmecomorba nylanderiae gen. et sp nov., a microsporidian parasite of the tawny crazy ant Nylanderia fulva. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 129:45-56 (DOI 10.1016/j.jip.2015.05.012).

- Rafiqi, A.M., Rajakumar, A., Abouheif, E. 2020. Origin and elaboration of a major evolutionary transition in individuality. Nature 585, 239–244. (doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2653-6).

- Rosas-Mejía, M., Guénard, B., Aguilar-Méndez, M. J., Ghilardi, A., Vásquez-Bolaños, M., Economo, E. P., Janda, M. 2021. Alien ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Mexico: the first database of records. Biological Invasions 23(6), 1669–1680 (doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02423-1).

- Sánchez-Restrepo, A.F., Chifflet, L., Confalonieri, V.A., Tsutsui, N.D., Pesquero, M.A., Calcaterra, L.A. 2020. A Species delimitation approach to uncover cryptic species in the South American fire ant decapitating flies (Diptera: Phoridae: Pseudacteon). PLOS ONE 15, e0236086 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0236086).

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Siddiqui, J.A., Bamisile, B.S., Khan, M.M., Islam, W., Hafeez, M., Bodlah, I., Xu, Y. 2021. Impact of invasive ant species on native fauna across similar habitats under global environmental changes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28(39), 54362–54382 (doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15961-5).

- Snelling, R. R.; Hunt, J. H. 1975. The ants of Chile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Chil. Entomol. 9: 63-129 (page 122, Combination in Paratrechina)

- Stukalyuk, S., Radchenko, Y., Gonchar, O., Akhmedov, A., Stelia, V., Reshetov, A., Shymanskyi, A. 2021. Mixed colonies of Lasius umbratus and Lasius fuliginosus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): when superparasitism may potentially develop into coexistence: a case study in Ukraine and Moldova. Halteres 12, 25–48 (doi:10.5281/zenodo.5753121).

- Tibcherani, M., Aranda, R., Mello, R.L. 2020. Time to go home: The temporal threshold in the regeneration of the ant community in the Brazilian savanna. Applied Soil Ecology 150, 103451 (doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.103451).

- Trigos-Peral, G., Abril, S., Angulo, E. 2020. Behavioral responses to numerical differences when two invasive ants meet: the case of Lasius neglectus and Linepithema humile. Biological Invasions (doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02412-4).

- Wang, Z., Moshman, L., Kraus, E.C., Wilson, B.E., Acharya, N. & Diaz, R. 2016. A review of the Tawny Crazy Ant, Nylanderia fulva, an emergent ant invader in the southern United States: Is biological control a feasible management option?. Insects, 7(4), 77 (DOI 10.3390/insects7040077).

- Wetterer, J.K. 2022. New-world spread of the Old-world Robust Crazy Ant, Nylanderia bourbonica (Forel) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology, 69(2), e7343 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v69i2.7343).

- Williams, J.L., Zhang, Y.M., LaPolla, J.S., Schultz, T.R., Lucky, A. 2022. Phylogenetic delimitation of morphologically cryptic species in globetrotting Nylanderia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) species complexes. Insect Systematics and Diversity 6 (1): 10:1-15 (doi:10.1093/isd/iaxb027).

- Williams, J.L., Zhang, Y.M., Lloyd, M.W., LaPolla, J.S., Schultz, T.R., Lucky, A. 2020. Global domination by crazy ants: phylogenomics reveals biogeographical history and invasive species relationships in the genus Nylanderia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Systematic Entomology 45, 730–744 (doi:10.1111/syen.12423).

- Zhang, Q. H., D. L. McDonald, D. R. Hoover, J. R. Aldrich, and R. G. Schneidmiller. 2015. North American Invasion of the Tawny Crazy Ant (Nylanderia fulva) Is Enabled by Pheromonal Synergism from Two Separate Glands. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 41:853-858. doi:10.1007/s10886-015-0622-6

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Araujo Castilho G., F. Barbosa Noll, E. R. da Silva, and E. F. dos Santos. 2011. Diversidade de Formicidae (Hymenoptera) em um fragmento de Floresta Estacional Semidecídua no Noroeste do estado de São Paulo, Brasil. R. bras. Bioci., Porto Alegre 9(2): 224-230.

- Badano, E.I., H.A. Regidor, H.A. Nunez, R. Acosta and E. Gianoli. 2005. Species richness and structure of ant communities in a dynamic archipelago: effects of island area and age. Journal of Biogeography

- Brandao, C.R.F. 1991. Adendos ao catalogo abreviado das formigas da regiao neotropical (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 35: 319-412.

- Bruch C. 1914. Catálogo sistemático de los formícidos argentinos. Revista del Museo de La Plata 19: 211-234.

- Calcaterra L. A., F. Cuezzo, S. M. Cabrera, and J. A. Briano. 2010. Ground ant diversity (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Ibera nature reserve, the largest wetland of Argentina. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 103(1): 71-83.

- Calcaterra L. A., S. M. Cabrera, F. Cuezzo, I. J. Perez, and J. A. Briano. 2010. Habitat and Grazing Influence on Terrestrial Ants in Subtropical Grasslands and Savannas of Argentina. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 103(4): 635-646.

- Caldart V. M., S. Iop, J. A. Lutinski, and F. R. Mello Garcia. 2012. Ants diversity (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of the urban perimeter of Chapecó county, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoociências 14 (1, 2, 3): 81-94.

- Calixto J. M. 2013. Lista preliminar das especies de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do estado do Parana, Brasil. Universidad Federal do Parana 34 pages.

- Corassa J. N., I. C. Magistrali, J. C. Moreno, E. B. Cantarelli, and A. Corassa. Effect of formicid granulated baits on non-target ants biodiversity in eucalyptus plantations litter. Comunicata Scientiae 4(1): 35-42.

- Cuezzo, F. 1998. Formicidae. Chapter 42 in Morrone J.J., and S. Coscaron (dirs) Biodiversidad de artropodos argentinos: una perspectiva biotaxonomica Ediciones Sur, La Plata. Pages 452-462.

- Drose W., L. R. Podgaiski, C. Fagundes Dias, M. de Souza Mendonca. 2019. Local and regional drivers of ant communities in forest-grassland ecotones in South Brazil: A taxonomic and phylogenetic approach. Plos ONE 14(4): e0215310.

- Emery C. 1906. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. XXVI. Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 37: 107-194.

- Feener Jr., D.H., M.R. Orr, K.M. Wackford, J.M. Longo, W.W. Benson and L.E. Gilbert. 2008. Geographic Variation in Resource Dominance-Discovery in Brazilian Ant Communities. Ecology 89(7):1824-1836

- Fernández F. 2000. Notas taxonómicas sobre la hormiga loca (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Paratrechina fulva) en Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Entomología 26: 145-149.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Figueiredo C. J. de, R. R. da Silva, C. de Bortoli Munhae, and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2013. Ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) attracted to underground traps in Atlantic Forest. Biota Neotrop 13(1): 176-182

- Forel A. 1908. Ameisen aus Sao Paulo (Brasilien), Paraguay etc. gesammelt von Prof. Herm. v. Ihering, Dr. Lutz, Dr. Fiebrig, etc. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 58: 340-418.

- Forel A. 1909. Ameisen aus Guatemala usw., Paraguay und Argentinien (Hym.). Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift 1909: 239-269.

- Forel A. 1911. Ameisen des Herrn Prof. v. Ihering aus Brasilien (Sao Paulo usw.) nebst einigen anderen aus Südamerika und Afrika (Hym.). Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift 1911: 285-312.

- Forel A. 1912. Formicides néotropiques. Part VI. 5me sous-famille Camponotinae Forel. Mémoires de la Société Entomologique de Belgique. 20: 59-92.

- Forel A. 1913. Fourmis d'Argentine, du Brésil, du Guatémala & de Cuba reçues de M. M. Bruch, Prof. v. Ihering, Mlle Baez, M. Peper et M. Rovereto. Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles. 49: 203-250.

- Ilha C., J. A. Lutinski, D. Von Muller Pereira, F. R. Mello Garcia. 2009. Riqueza de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Bacia da Sanga Caramuru, municipio de Chapeco-SC. Biotemas 22(4): 95-105.

- Kamura C. M., M. S. C. Morini, C. J. Figueiredo, O. C. Bueno, and A. E. C. Campos-Farinha. 2007. Ant communities (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in an urban ecosystem near the Atlantic Rainforest. Braz. J. Biol. 67(4): 635-641.

- Kamura, C.M., M.S.C. Morini, C.J. Figueiredo, O.C. Bueno, and A.E.C. Campos-Farinha. 2007. Comunidades de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) em um ecossistema urbano próximo à Mata Atlântica. Brazilian Journal of Biology 67(4): 635-641

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Kusnezov N. 1956. Claves para la identificación de las hormigas de la fauna argentina. Idia 104-105: 1-56.

- Kusnezov N. 1978. Hormigas argentinas: clave para su identificación. Miscelánea. Instituto Miguel Lillo 61:1-147 + 28 pl.

- Luederwaldt H. 1918. Notas myrmecologicas. Rev. Mus. Paul. 10: 29-64.

- Lutinski J. A., B. C. Lopes, and A. B. B.de Morais. 2013. Diversidade de formigas urbanas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de dez cidades do sul do Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 13(3): 332-342.

- Lutinski J. A., F. R. Mello Garcia, C. J. Lutinska, and S. Iop. 2008. Ants diversity in Floresta Nacional de Chapecó in Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Ciência Rural, Santa Maria 38(7): 1810-1816.

- Maciel L., J. Iantas, F. C. Gruchowski-W, and D. R. Holdefer. 2011. INVENTORY OF FAUNA OF ANTS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION FLORISTIC ENVIRONMENT IN THE CITY OF UNION OF VICTORIA, PARANA, BRAZIL. Biodiversidade Pampeana Pucrs, Uruguiana 9(1): 38-43.

- Maes, J.-M. and W.P. MacKay. 1993. Catalogo de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia 23.

- Medeiros Macedo L. P., E. B. Filho, amd J. H. C. Delabie. 2011. Epigean ant communities in Atlantic Forest remnants of São Paulo: a comparative study using the guild concept. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(1): 7578.

- Mello Garcia F. R., C. Charlier Ahlert, B. Ribeiro de Freitas, M. Morel Trautmann, S. Pirotta Tancredo, and J. A. Lutinski. 2011. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in five hospitals of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Maringá 33(2): 203-209.

- Mentone T. O., E. A. Diniz, C. B. Munhae, O. C. Bueno, and M. S. C. Morini. 2011. Composition of ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at litter in areas of semi-deciduous forest and Eucalyptus spp., in Southeastern Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 11(2): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v11n2/en/abstract?inventory+bn00511022011.

- Morini M. S. de C., C. de B. Munhae, R. Leung, D. F. Candiani, and J. C. Voltolini. 2007. Comunidades de formigas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) em fragmentos de Mata Atlântica situados em áreas urbanizadas. Iheringia, Sér. Zool., Porto Alegre, 97(3): 246-252.

- Munhae C. B., Z. A. F. N. Bueno, M. S. C. Morini, and R. R. Silva. 2009. Composition of the Ant Fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Public Squares in Southern Brazil. Sociobiology 53(2B): 455-472.

- Oliveira Mentone T. de, E. A. Diniz, C. de Bortoli Munhae, O. Correa Bueno and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2012. Composition of ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at litter in areas of semi-deciduous forest and Eucalyptus spp., in Southeastern Brazil. Biota Neotrop 11(2): 237-246.

- Oliveira R. F., L. C. de Almeida, D. R. de Suza, C. Bortoli Munhae, O. C. Bueno, and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2012. Ant diversity (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and predation by ants on the different stages of the sugarcane borer life cycle Diatraea saccharalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 109: 381387.

- Osorio Rosado J. L, M. G. de Goncalves, W. Drose, E. J. Ely e Silva, R. F. Kruger, and A. Enimar Loeck. 2013. Effect of climatic variables and vine crops on the epigeic ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Campanha region, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Insect Conserv 17: 1113-1123.

- Pacheco R., and H. L. Vasconcelos. 2007. Invertebrate conservation in urban areas: ants in the Brazilian Cerrado. Landscape and Urban Planning 81: 193199.

- Pacheco, R., R.R. Silva, M.S. de C. Morini, C.R.F. Brandao. 2009. A Comparison of the Leaf-Litter Ant Fauna in a Secondary Atlantic Forest with an Adjacent Pine Plantation in Southeastern Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 38(1):055-065

- Pignalberi C. T. 1961. Contribución al conocimiento de los formícidos de la provincia de Santa Fé. Pp. 165-173 in: Comisión Investigación Científica; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Argentina) 1961. Actas y trabajos del primer Congreso Sudamericano de Zoología (La Plata, 12-24 octubre 1959). Tomo III. Buenos Aires: Librart, 276 pp.

- Piva A., and A. E. de C. Campos. 2012. Ant Community Structure (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Two Neighborhoods with Different Urban Profiles in the City of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Psyche 2012 (390748): 1-8

- Rosa da Silva R. 1999. Formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) do oeste de Santa Catarina: historico das coletas e lista atualizada das especies do Estado de Santa Catarina. Biotemas 12(2): 75-100.

- Rosado J. L. O., M. G. de Gonçalves, W. Dröse, E. J. E. e Silva, R. F. Krüger, R. M. Feitosa, and A. E. Loeck. 2012. Epigeic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in vineyards and grassland areas in the Campanha region, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Check List, Journal of species lists and distribution 8(6): 1184-1189.

- Santoandre S., J. Filloy, G. A. Zurita, and M. I. Bellocq. 2019. Ant taxonomic and functional diversity show differential response to plantation age in two contrasting biomes. Forest Ecology and Management 437: 304-313.

- Santschi F. 1912. Quelques fourmis de l'Amérique australe. Revue Suisse de Zoologie 20: 519-534.

- Santschi F. 1925. Fourmis des provinces argentines de Santa Fe, Catamarca, Santa Cruz, Córdoba et Los Andes. Comunicaciones del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural "Bernardino Rivadavia" 2: 149-168.

- Silvestre R., M. F. Demetrio, and J. H. C. Delabie. 2012. Community Structure of Leaf-Litter Ants in a Neotropical Dry Forest: A Biogeographic Approach to Explain Betadiversity. Psyche doi:10.1155/2012/306925

- Souza D. R. de., T. T. Fernandes, J. R. de Oloveira Nascimento, S. S. Suguituru, and M. S. de C. Morini. 2012. Characterization of ant communities (Hymenoptera Formicidae) in twigs in the leaf litter of the Atlantic rainforest and Eucalyptus trees in the southeast region of Brazil. Psyche 2012(532768): 1-12

- Suguituru S. S., D. R. de Souza, C. de Bortoli Munhae, R. Pacheco, and M. S. de Castro Morini. 2011. Diversidade e riqueza de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) em remanescentes de Mata Atlântica na Bacia Hidrográfica do Alto Tietê, SP. Biota Neotrop. 13(2): 141-152.

- Suguituru S. S., R. Rosa Silva, D. R. de Souza, C. de Bortoli Munhae, and M. Santina de Castro Morini. Ant community richness and composition across a gradient from Eucalyptus plantations to secondary Atlantic Forest. Biota Neotrop. 11(1): 369-376.

- Ulyssea M.A., C. E. Cereto, F. B. Rosumek, R. R. Silva, and B. C. Lopes. 2011. Updated list of ant species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) recorded in Santa Catarina State, southern Brazil, with a discussion of research advances and priorities. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 55(4): 603-611.

- Vittar, F. 2008. Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la Mesopotamia Argentina. INSUGEO Miscelania 17(2):447-466

- Vittar, F., and F. Cuezzo. "Hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de la provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina." Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina (versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471) 67, no. 1-2 (2008).

- Wild, A. L. "A catalogue of the ants of Paraguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Zootaxa 1622 (2007): 1-55.

- Zolessi L. C. de, Y. P. Abenante, and M. E. de Philippi. 1988. Lista sistematica de las especies de Formicidos del Uruguay. Comun. Zool. Mus. Hist. Nat. Montev. 11: 1-9.

- Zolessi L. C. de; Y. P. de Abenante, and M. E. Philippi. 1989. Catálogo sistemático de las especies de Formícidos del Uruguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Montevideo: ORCYT Unesco, 40 + ix pp.

- de Souza D. R., S. G. dos Santos, C. de B. Munhae, and M. S. de C. Morini. 2012. Diversity of Epigeal Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Urban Areas of Alto Tietê. Sociobiology 59(3): 703-117.

- de Zolessi, L.C., Y.P. de Abenante and M.E. Philippi. 1987. Lista sistemática de las especies de formícidos del Uruguay. Comunicaciones Zoologicas del Museo de Historia Natural de Montevideo 11(165):1-9

- de Zolessi, L.C., Y.P. de Abenante and M.E. Phillipi. 1989. Catalago Systematico de las Especies de Formicidos del Uruguay (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Oficina Regional de Ciencia y Technologia de la Unesco para America Latina y el Caribe- ORCYT. Montevideo, Uruguay

- Common Name

- Invasive

- Supercolonies

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- South subtropical

- Phorid fly Associate

- Host of Pseudacteon convexicauda

- Microsporidian fungus Associate

- Host of Myrmecomorba nylanderiae

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis craccivora

- Host of Aphis vernoniae

- Host of Chaitophorus viminicola

- Host of Cinara juniperivora

- Host of Sanbornia juniperi

- Host of Shivaphis celti

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Formicinae

- Lasiini

- Nylanderia

- Nylanderia fulva

- Formicinae species

- Lasiini species

- Nylanderia species

- Ssr