Mycetomoellerius haytianus

| Mycetomoellerius haytianus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycetomoellerius |

| Species: | M. haytianus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycetomoellerius haytianus (Wheeler, W.M. & Mann, 1914) | |

Mann (Wheeler and Mann 1914) stated "The nest entrance opened directly on the surface of the ground and was not surrounded by a crater." Longino also collected a number of stray workers in scrub and riparian forest in Jamaica. Nothing else is known regarding this species.

Identification

A member of the Jamaicensis species group. Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2007) - M. haytianus was originally proposed as a subspecies of Mycetomoellerius jamaicensis. The brief description of Wheeler & Mann (1914) contained only characters that distinguished it from the typical form, such as shorter spines and tubercles on the posterior corners of the head, well-developed median pronotal tooth, and black coloration.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 18.95° to 18.43333333°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Haiti (type locality), Jamaica.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Queens and males are unknown.

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- haytianus. Atta (Trachymyrmex) jamaicensis subsp. haytiana Wheeler, W.M. & Mann, 1914: 41, fig. 18 (w.) HAITI.

- Combination in Trachymyrmex: Kempf, 1972a: 253.

- Combination in Mycetomoellerius: Solomon et al., 2019: 948.

- Status as species: Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão, 2007: 6.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Length: 3.5-4 mm.

Differing from the typical form in having the anterior spines or tubercles on the posterior corners of the head shorter, in having a well-developed, pointed median tubercle on the pronotum and in coloration, the body being entirely black, with the exception of the mandibles, funiculi, articulations of the legs and tarsi beyond the first joint, which are red.

Mayhe-Nunes and Brandao (2007) includes a more detailed description:

measurements (n = 3). TL 4.7 (4.5–4.9); DHL 1.28 (1.26–1.31); HW 1.28 (1.25–1.32); IFW 0.70 (0.69–0.71); ScL 1.08 (1.05–1.11); HWL 0.74 (0.68–0.78); MeL 1.82 (1.77–1.85); PL 0.34 (0.32–0.35); PPL 0.48 (0.45–0.51); GL 1.32 (1.25–1.37); HfL 1.84 (1.82–1.86).

Uniformly dark ferruginous, with lighter tip of tarsi and funiculi. Integument opaque and finely granulose. Pilosity scarce; very short hook-like hairs confined to body projections, more abundant on antennal scapes and gaster tip.

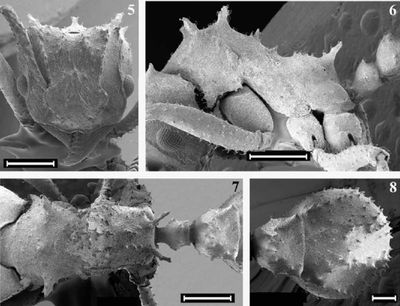

Head, in full face view, as long as broad (DCI average 100; 99–101). Outer border of mandible feebly sinuous; masticatory margin bears two apical and seven equally smaller teeth. Clypeus median apron without projections. Frontal area shallowly impressed. Frontal lobes semicircular, moderately approximate (FLI average 54; 54–55), with faintly crenulate free border, lacking prominent denticles on the antero-lateral border. Frontal carina moderately diverging caudad, reaching the antennal scrobe posterior end in a small tooth at its posterior end at the vertexal margin; preocular carina posteriorly ending in the posterior margin of the head as one or two small teeth of almost the same size of frontal carinae projections. Occipital spines longer and stouter than carinae projections. Supraocular projections absent or vestigial. Inferior corner of occiput with a small ridge, in side view. Eye convex, surpassing the head lateral border, with 13 facets in a row across the greatest diameter. Antennal scape, when lodged in the scrobe, projecting beyond the tips of the preocular carinae projections by nearly one fourth of its length; gradually thickened towards apex, covered with small piligerous tubercles.

Mesosoma. Pronotal dorsum emarginated in front and on sides; antero-inferior corner with a strong and truncated tooth; inferior margin with small piligerous denticles; median pronotal tooth tip rather truncate, not projected above the tips of the stronger lateral pronotal spines, which point obliquely upwards, with the pronotum in frontal view. Anterior pair of mesonotal spines a little shorter than the lateral pronotal projections, directed upwards; the spine-like second and third pair gradually smaller and thinner. Anterior margin of katepisternum smooth, without a projecting tooth. Metanotal constriction shallowly impressed. Basal face of propodeum laterally marginated by a row of three denticles on each side; propodeal spines pointing obliquely and laterad, as long as the distance between their inner bases. Hind femora almost of the same length of mesosoma.

Waist and gaster. Dorsum of petiolar node with a pair of minute spines, the sides subparallel in dorsal view, the spiracles produced as small tubercular projections; sternum without sagital keel. Postpetiole trapezoidal in dorsal view, two times broader behind than in front, and shallowly impressed dorsally, with straight postero-dorsal border. Gaster, when seen from above, globose to suboval. Tergum I with convex lateral faces separated from the dorsal face by a longitudinal row of piligerous tubercles on each side; anterior two thirds of dorsum with three shallow longitudinal furrows separated by a pair of piligerous tubercles rows. Sternum I without an anterior sagital keel or prominent tubercles.

Type Material

Described from several workers taken from a single colony in a canyon near PetionviIle.

Mayhé-Nunes & Brandão (2007) - Lectotype worker: HAITI: Petionville, Mann leg. [no date] (“cotype” deposited in National Museum of Natural History, examined, here designated). Paralectotype workers: same data as lectotype (5 deposited in USNM, 2 deposited in Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo, 1 deposited in Instituto de Biologia Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro). Wheeler & Mann (1914) say that this species was described from several workers collected from a single colony. Although we found only three individuals clearly labeled as “cotypes”, the other six workers bear identical locality labels, and so were considered as paralectotypes.

References

- Mayhé-Nunes, A.J., Brandão, C.R.F. 2007. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 3: The Jamaicensis group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa. 1444:1-21 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1444.1.1).

- Solomon, S.E., Rabeling, C., Sosa-Calvo, J., Lopes, C.T., Rodrigues, A., Vasconcelos, H.L., Bacci Jr, M., Mueller, U.G., Schultz, T.R. 2019. The molecular phylogenetics of Trachymyrmex Forel ants and their fungal cultivars provide insights into the origin and coevolutionary history of ‘higher-attine’ ant agriculture. Systematic Entomology 44: 939-956 (doi:10.1111/syen.12370).

- Wheeler, W. M.; Mann, W. M. 1914. The ants of Haiti. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 33: 1-61.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Lubertazzi D. 2019. The ants of Hispaniola. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 162(2): 59-210.

- Mayhe-Nunes A. J., and C. R. F. Brandao. 2007. Revisionary studies on the attine ant genus Trachymyrmex Forel. Part 3: The Jamaicensis group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 1444: 1-21.

- Perez-Gelabert D. E. 2008. Arthropods of Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti): A checklist and bibliography. Zootaxa 1831:1-530.

- Wheeler W. M., and W. M. Mann. 1914. The ants of Haiti. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 33: 1-61.