Formica ravida

| Formica ravida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Formicinae |

| Tribe: | Formicini |

| Genus: | Formica |

| Species group: | rufa |

| Species: | F. ravida |

| Binomial name | |

| Formica ravida Creighton, 1940 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

This mound building ant in the Formica rufa group nests in open areas and feeds on insects and secretions from Homoptera. It is a known host for Formicoxenus hirticornis in New Mexico.

Photo Gallery

Identification

The tentorial pits of this species are shallow. The erect bristles on the tibiae are restricted to two rows on the flexor surface, which extend nearly the entire length of the tibiae. The erect hairs on the gaster are scattered, and do not form an even vestiture when viewed in profile, although the gaster is covered with dense, gray, appressed pubescence. The petiole is narrow in profile with a moderately sharp apex (MacKay & MacKay 2002). There are several short erect hairs coming out of the compound eyes.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Western North America.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 50.1° to 34.15°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Habitat

Various; from prairies up to pine forests.

Biology

This ant is a presumed temporary social parasite of other species of Formica in the fusca group. It is a very aggressive ant that readily defends its large mound nests by squirting formic acid. Temnothorax andrei may be occasionally found within this mound nest. Incipient F. ravida nests may be found under logs or stones. In northwestern New Mexico on the Navajo Reservation, this ant was found at 1,492 meters elevation near the San Juan River just outside of Shiprock New Mexico in an open pasture. Deep within these host nests, the guest or xenobiont Formicoxenus hirticornis has been found.

In Colorado, Gregg (1963) found this species in mixed and deciduous forests, pinyon-juniper woodland, grassland, and sagebrush desert. In North Dakota we (Wheeler and Wheeler, 1977: 10) reported it as a grassland species which preferred shrubby areas, mostly sagebrush. The nest is usually started under a stone or around the base of some small plant (frequently sagebrush). In some nests very little thatch is used, but dome-like thatch mounds are common, averaging 20 cm in height and 60 cm in diameter. The large thatch domes have numerous entrances over all parts of the surface.

Mackay and Mackay (2002) - Nests are usually in the form of thatched mounds on the sides of logs and stumps. Incipient nests may be found under stones or logs, but usually some thatching is present. These ants are extremely aggressive. Workers fold the gaster under the body and squirt a stream of formic acid several centimeters. This acid is strong enough to cause blistered skin, after repeated contact with these ants.

Nevada, Wheeler and Wheeler (1986) - Our 40 records are from 26 localities, which are widely scattered north of the Hot Desert except none in the northwest; 4,300-8,800 ft. Six records were from the Cool Desert (1 from a cottonwood grove), 11 were from the Pinyon-Juniper Biome, and 1from the Coniferous Forest. The nest structure (Fig. 41) is so varied that we give all our recorded descriptions; no two were alike: under horizontal buried sagebrush trunk; thatch mound around rotten log 1 m long; under slightly buried stone with excavated soil at one end of stone; under several contiguous partly buried stones with excavated soil at edge of largest stone; under a slightly buried stone; thatch 15 cm deep on horizontal dead sagebrush trunk and nearby thatch 38 cm in diameter around erect dead sagebrush trunk: a polycalic cluster of 7 thatch mounds 1 ½ - 7 1/2 m apart, each thatch mound on top of a large deeply buried stone except 1 around a dead Purshia trunk, thatch mostly pine needles; asymmetrical thatch mound 94 x 102 cm, of pine needles; asymmetrical thatch mound against a juniper stump, thatch of juniper needles; under old lumber and piece of tin roofing, debris piled around timber; under a log 60 cm long and 30 cm in diameter. Our notes on the behavior of one colony can serve as a sample for the species: fast, aggressive, bite annoying; workers patrolling pine trunks and numerous on the ground; certainly the dominant animal in that habitat.

Nest site selected in open areas devoid of cover or in areas of moderate to sparse cover. Nest begun at the base of some small plant (frequently sagebrush) or under log or stone with many of the passages running into the soil. Moderate to extensive use made of thatching, often little of this visible on the outside of the nest. The finished nest may or may not consist of a large mound of collected detritus. (Creighton, 1940)

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Other Ants

Nests of this species occasionally host Temnothorax andrei, although the nature of the relationship is unknown (Mackay & Mackay, 1984).

Other Insects

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon cothurnatus (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

- This species is a prey for the Microdon fly Microdon piperi (a predator) (Quevillon, 2018).

Flight Period

| X | X | X | |||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Castes

Worker

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Images from AntWeb

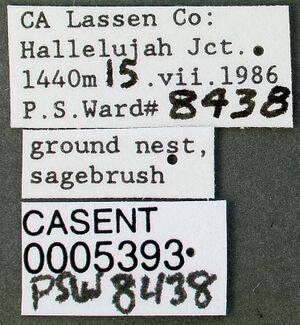

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0005393. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by UCDC, Davis, CA, USA. |

- Male

| |

| . | |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- ravida. Formica rufa subsp. ravida Creighton, 1940a: 1, fig. 1 (w.q.m.) U.S.A. [First available use of Formica truncicola subsp. integroides var. ravida Wheeler, W.M. 1913f: 560; unavailable name.] Subspecies of obscuripes: Creighton, 1950a: 493. Raised to species: Gregg 1963: 581. Junior synonym of haemorrhoidalis Creighton: Brown, 1965d: 181. [F. haemorrhoidalis Creighton, 1940a: 1, junior primary homonym of F. haemorrhoidalis Latreille, 1802c: 276.] F. ravida designated as first available replacement name and senior synonym of tahoensis: Bolton, 1995b: 202.

- haemorrhoidalis. Formica rufa subsp. haemorrhoidalis Creighton, 1940a: 1, fig. 1 (w.) U.S.A. [First available use of Formica rufa subsp. integra var. haemorrhoidalis Emery, 1893i: 652 (w.); Wheeler, W.M. 1913f: 441 (q.m.); unavailable name.] [Junior primary homonym of Formica haemorrhoidalis Latreille, 1802c: 276, above.] Replacement name: ravida Creighton, 1940a: 1 (designated first available replacement name by Bolton, 1995b: 202, as haemorrhoidalis Creighton was raised to species and made senior synonym of ravida and tahoensis by Brown, 1965d: 181).

- tahoensis. Formica rufa subsp. tahoensis Creighton, 1940a: 1, fig. 1 (w.q.) U.S.A. [First available use of Formica truncicola subsp. integroides var. tahoensis Wheeler, W.M. 1917a: 538; unavailable name.] Cole, 1956g: 260 (q.m.). Subspecies of integra: Creighton, 1950a: 488. Junior synonym of haemorrhoidalis: Brown, 1965d: 181; of ravida: Bolton, 1995b: 205.

Type Material

- Formica ravida: Syntype, 7 workers, 2 queens, Elkhorn, Montana, United States, 46°16′29″N 111°56′46″W / 46.27483°N 111.94623°W, W.M. Mann, Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Description

This description is taken from Wheeler, W.M. 1913i under the name Formica truncicola subspecies integroides var ravida which is an unavailable name.

Worker. Length 4-6 mm.

Like the var. haemorrhoidalis Emery in pubescence and sculpture and in lacking erect hairs, except on the gaster, but differing in color. The red of the head, thorax, and petiole is much deeper and not yellowish, the legs, whole of the funiculi, tips of the scapes and the gaster are black and even the largest workers have a large black spot on the pro- and mesonotum. In small workers the red color is darker and more brownish, the whole thorax is blackish and the posterior portion of the head and the whole of the scapes are infuscated. The surface of the body in all of the workers is opaque, the pubescence on the gaster short, dense and dark gray in color; the red anal spot is much restricted.

Female. Lengthe 8.5-9 mm.

Differing from the female of haemorrhoidalis in having the tips of the scapes, the posterior border of the pronotum, three spots on the mesonotum, the whole of the scutellum and metanotum, a few spots on the mesoleurae and the middle and hing legs, including their coxae, black.

References

- Bolton, B. 1995b. A new general catalogue of the ants of the world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 504 pp. (page 202, senior synonym of tahoensis; new synonymy)

- Borowiec, M.L., Cover, S.P., Rabeling, C. 2021. The evolution of social parasitism in Formica ants revealed by a global phylogeny. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2026029118 (doi:10.1073/pnas.2026029118).

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1965d. Studies on North American ants. I. The Formica integra subgroup. Entomol. News 76: 181-186. (page 181, junior synonym of haemorrhoidalis)

- Creighton, W. S. 1940a. A revision of the North American variants of the ant Formica rufa. American Museum Novitates 1055: 1-10. (page 1, worker, queen described)

- Creighton, W. S. 1950a. The ants of North America. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 104: 1-585 (page 493, subspecies of obscruipes)

- Gregg, R.E. 1963. The Ants of Colorado. University of Colorado Press. xvi + 792 pp. (page 581, raised to species)

- Mackay, W.P. & Mackay, E.E. 2002. The Ants of New Mexico: 400 pp. Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, N.Y.

- Ruano, F., Tinaut, A., Soler, J.J. 2000. High surface temperatures select for individual foraging in ants. Behavioral Ecology 11, 396-404.

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Wheeler, G. C. and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles.

- Wheeler, W. M. 1913i. A revision of the ants of the genus Formica (Linné) Mayr. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 53: 379-565. (page 560, First available use of Formica truncicola subsp. integroides var. ravida Wheeler.; unavailable name.)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Allred D. M. 1982. Ants of Utah. The Great Basin Naturalist 42: 415-511.

- Allred, D.M. 1982. The ants of Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 42:415-511.

- Beck D. E., D. M. Allred, W. J. Despain. 1967. Predaceous-scavenger ants in Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 27: 67-78

- Borchert, H.F. and N.L. Anderson. 1973. The Ants of the Bearpaw Mountains of Montana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 46(2):200-224

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Cole, A.C. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68(2):34-39

- Glasier J. R. N., S. Nielsen, J. H. Acorn, L. H. Borysenko, and T. Radtke. 2016. A checklist of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Saskatchewan. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 130(1): 40-48.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Knowlton G. F. 1970. Ants of Curlew Valley. Proceedings of the Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 47(1): 208-212.

- La Rivers I. 1968. A first listing of the ants of Nevada. Biological Society of Nevada, Occasional Papers 17: 1-12.

- Lavigne R., and T. J. Tepedino. 1976. Checklist of the insects in Wyoming. I. Hymenoptera. Agric. Exp. Sta., Univ. Wyoming Res. J. 106: 24-26.

- Longino, J.T. 2010. Personal Communication. Longino Collection Database

- Michigan State University, The Albert J. Cook Arthropod Research Collection. Accessed on January 7th 2014 at http://www.arc.ent.msu.edu:8080/collection/index.jsp

- MontBlanc E. M., J. C. Chambers, and P. F. Brussard. 2007. Variation in ant populations with elevation, tree cover, and fire in a Pinyon-Juniper-dominated watershed. Western North American Naturalist 67(4): 469491.

- Rees D. M., and A. W. Grundmann. 1940. A preliminary list of the ants of Utah. Bulletin of the University of Utah, 31(5): 1-12.

- Shattuck S. O. 1985. Illustrated key to ants associated with western spruce budworm. United States Department of Agriculture. Agriculture Handbook 632: 1-36.

- Smith M. R. 1952. On the collection of ants made by Titus Ulke in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the early nineties. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 60: 55-63.

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1987. A Checklist of the Ants of South Dakota. Prairie Nat. 19(3): 199-208.

- Wheeler J. N., G. C. Wheeler, R. J. Lavigne, T. A. Christiansen, and D. E. Wheeler. 2014. The ants of Yellowstone National Park. Lexington, Ky. : CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013. 112 pages.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. On the founding of colonies by queen ants, with special reference to the parasitic and slave-making species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 22: 33-105.

- Wheeler W. M. 1913. A revision of the ants of the genus Formica (Linné) Mayr. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 53: 379-565.

- Wheeler W. M. 1917. The mountain ants of western North America. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 52: 457-569.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1963. Ants of North Dakota

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Montana. Psyche 95:101-114

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Wyoming. Insecta Mundi 2(3&4):230-239

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Ant Associate

- Host of Formicoxenus hirticornis

- Host of Temnothorax andrei

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Rhopalosiphum nymphaeae

- ''Microdon'' fly Associate

- Host of Microdon cothurnatus

- Host of Microdon piperi

- FlightMonth

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Formicinae

- Formicini

- Formica

- Formica ravida

- Formicinae species

- Formicini species

- Formica species

- Ssr

- Rufa group