Trichomyrmex destructor

| Trichomyrmex destructor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Crematogastrini |

| Genus: | Trichomyrmex |

| Species group: | destructor |

| Species: | T. destructor |

| Binomial name | |

| Trichomyrmex destructor (Jerdon, 1851) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Mizo-hime-ari | |

| Language: | Japanese |

| Singapore ant | |

| Language: | English |

A widespread invasive species originally described from India and occurring in tropical and subtropical regions of the world (Wetterer 2009b), supposedly spread from central Asia west to north Africa (Forel 1909; Sharaf 2006), southern Europe (Ruzsky 1907) and the Arabian Peninsula (Collingwood 1985; Collingwood and Agosti 1996). In the USA it is reported from Key West and Tampa (Deyrup et al. 2000).

| At a Glance | • Highly invasive • Supercolonies |

Identification

Polymorphic workers.

Trichomyrmex destructor is very similar to the closely related Trichomyrmex robustior, but is lighter in color and the eyes tend to be less elongate. Workers within nests also show more allometric variation than is found in T. robustior (Heterick 2006).

From Bolton (1987) Worker. TL 1-8-3-5, HL 0-50-0-88, HW 0-40-0-79, CI 76-92, SL 0-41-0-56, SI 70-104, PW 0-23-0-45, AL 0-54-0-92 (55 measured).

Workers showing marked size variation in any given series, and displaying monophasic allometric variation. Mandibles with 3 strong teeth, the fourth (basal) reduced to a minute offset denticle. Mandibles usually with distinct longitudinal rugulose or striate sculpture, even in the smallest workers. Only rarely the smallest workers with mandibles virtually smooth. Eyes relatively small, the maximum diameter 0-14-0-20 x HW and with 4-6 ommatidia in the longest row. In general eyes of smaller workers relatively somewhat larger in relation to head width than in larger workers, but not as conspicuously so as in oscaris. In larger workers CI is higher than in smaller workers, the heads becoming relatively broader with increased size.

Antennal scapes relatively longer in small workers and shorter in larger individuals, as follows.

- When HW 0-40-0-45 then SI is 104-95

- when HW 0-45-0-55 then SI is 97-85

- when HW 0-55-0-65 then SI is 86-76

- when HW 0-65-0-79 then SI is 78-70

Note that within the size intervals given the scapes are always relatively longer here than in oscaris (see below). Scapes when laid straight back from their insertions reaching the occipital margin in smallest workers but falling short of the margin in larger individuals. Alitrunk in profile with promesonotum convex and metanotal groove impressed. Petiole node in dorsal view globular to subglobular, not distinctly anteroposteriorly compressed. Occipital margin of head with 2-4 pairs of hairs forming a transverse row.

Dorsum of head in front of this row but behind the frontal lobes with 1-4 pairs of hairs straddling the midline. Pubescence on head sparse and directed towards the midline. Promesonotal dorsum always with numerous elongate standing hairs; such hairs usually present on propodeum but may be lacking in small workers. Petiole, postpetiole and gaster with backward directed elongate hairs.

Cephalic dorsum unsculptured except for scattered hair-pits. A band of fine transverse striolate sculpture present on the rim of the descending occipital surface of the head; this band of weak sculpture usually just visible in full-face view along the rim of the occipital margin. In the smallest workers this sculpture may be very faint or rarely even absent. Propodeal dorsum always finely transversely striolate to rugulose and usually with punctulate sculpture also present, at least in larger workers of any given series. The transverse sculpture is fainter in smaller than in larger workers but the overall intensity of the sculpture may vary between series. Promesonotum usually smooth and shining with scattered hair-pits, but peripheral faint sculpture may occur in large workers. Sides of pronotum smooth to vestigially striolate, the remainder of the sides of the alitrunk punctate to reticulate-punctate; the sculpture more intense and wider distributed in larger than in smaller workers. First gastral tergite smooth except for hair-pits. Head, alitrunk, petiole and postpetiole uniformly glossy yellow, varying in shade from light yellow to dull brownish yellow. Gaster always much darker, dark brown to blackish brown, usually with a conspicuous yellowish area mediobasally, the extent of which is very variable but is sometimes absent, leaving the gaster uniformly dark.

Two closely related species occur in sub-Saharan Africa, Trichomyrmex oscaris and Trichomyrmex mayri. The latter matches the description of destructor given above but is uniformly dark brown to blackish brown; see under mayri for further discussion. Trichomyrmex oscaris is uniformly coloured, unlike destructor, and has the petiole and postpetiole shaped differently in larger workers. Apart from this the antennal scapes of destructor are relatively longer than those of oscaris in workers of comparable absolute dimensions, compare the tables given under their respective descriptions.

Sharaf et al. (2016) – Arabian Peninsula The most similar species to T. destructor is Trichomyrmex mayri, from which it can be distinguished only by the bicoloured body. Head, mesosoma, petiole and postpetiole yellow to brown yellow, gaster dark brown, whereas Trichomyrmex mayri is unicolorous dark brown or black brown.

Keys including this Species

- Key to Afrotropical Erromyrma, Monomorium, Syllophopsis and Trichomyrmex species

- Key to Arabian Trichomyrmex species

- Key to Australian Monomorium Species

- Key to Malagasy Erromyrma, Monomorium, Syllophopsis and Trichomyrmex species

- Key to Micronesian Ants

- Key to Monomorium of the southwestern Australian Botanical Province

- Key to Myrmicinae genera of the southwestern Australian Botanical Province

- Key to Trichomyrmex

- Key to workers of the Socotra Archipelago, Yemen

Distribution

Trichomyrmex destructor has a widespread distribution in tropical and subtropical parts of the Old World, except in sub-Saharan Africa. In the New World, however, it is found only in Florida (where it is rare, being only known from Key West and Tampa (Deyrup, Davis & Cover, 2000)), the West Indies, and the Galapagos Islands (Wetterer 2009).

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 32.812778° to 6.4°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Afrotropical Region: Cape Verde, Comoros, Eritrea, Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, Saudi Arabia, Socotra Archipelago, South Africa, United Arab Emirates, United Republic of Tanzania, Yemen.

Australasian Region: Australia.

Indo-Australian Region: Cook Islands, Fiji, Guam, Indonesia, Kiribati, Krakatau Islands, Micronesia (Federated States of), New Guinea, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Philippines, Samoa, Singapore, Solomon Islands.

Malagasy Region: Madagascar, Mauritius, Mayotte, Seychelles.

Nearctic Region: United States.

Neotropical Region: Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Galapagos Islands, Greater Antilles, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago.

Oriental Region: Bangladesh, Cambodia, India (type locality), Laos, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand.

Palaearctic Region: Afghanistan, Canary Islands, China, Cyprus, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Japan, Kuwait, Oman, Türkiye, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Uzbekistan.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

As reported from the Global Invasive Species Database:

Nest outdoors or in buildings, depending largely on whether they occur in tropical, semitropical or temperate regions. In northern Western Australia they do not live far from houses where they live above the ground in wall and roof cavities. They are present in some tropical, irrigated, lowland rice fields in the Philippines, and coconut plantations in Sri Lanka. In Florida they nest in soil (lawns) or buildings. On Tiwi Island and in Australia's Northern Territory, T. destructor nests were only associated with urban areas; while there was some spread into surrounding bush land, they appear to be unable to establish in undisturbed habitat. In the United Arab Emirates the ants are present in a wide range of habitats, especially irrigated gardens and disturbed habitats close to water. In the Caribbean they were found nesting in trees in citrus orchards (in hollow twigs and branches) and on the ground (Collingwood et al. 1997; and Harris et al. 2005).

Trichomyrmex destructor is a tramp ant, renowned for transportation via human commerce and trade. It is associated with a wide range of freight types, making it difficult to target any particular pathways. This ant also spreads naturally from established colonies in two ways: colony budding, where queens walk on foot accompanied by workers to a new nesting site; and winged dispersal of inseminated queens to uninfested areas where they start a new colony. This latter mechanism needs to be confirmed; it is most likely colony budding is the primary natural dispersal method (Harris et al. 2005).

Regional Information

Arabian Peninsula

Sharaf et al. (2016) – Workers of this species were foraging close to the trunk base of an Acacia sp. tree where the surrounding area was impacted by trash and human waste. Another nest series was found in moist soil under a stone next to a date palm, Phoenix dactylifera L. (Arecaceae). A nest series was also found under rooster tree, Calotropis procera (Aiton) W.T. Aiton (Asclepiadaceae).

Madagascar

Heterick (2006) - Samples have been taken in tropical dry forest in north and north-western Madagascar in the Antsiranana and Jahajanga Provinces, where they have been collected under stones, from a dead branch and by sweeping. Populations also may be expected to occur generally in severely damaged habitats in these regions.

Yemen

Sharaf et al. (2017) - Trichomyrmex destructor is one of the most successful invasive species on Socotra Island, occupying diverse habitats. It was found nesting directly in soil under a rock. Several workers were found in leaf litter under Eragrostis eragrostis (L.) (Poaceae), where the soil was dry and rich in organic material. Several individuals were nesting under a rock in very moist, compact, clay soil. A nest was found under the bark of a dead rotten log located on a mountainside where a small stream was draining a mountain crest surrounded by diverse plant communities. Another nest series was found in leaf litter under a tree of Ficus cordata Thunb (Moraceae).

Associations with Humans

Wetterer (2009) reported:

"In the past, T. destructor was primarily spread by ship. For example, CLARKE (1922) reported T. destructor was a serious problem on steamers traveling between California and the East Coast US via Panama Canal, writing that T. destructor "not only caused a considerable pecuniary loss in the destruction of food stuffs but attacked passengers and crew… They would find their way in small or large numbers into the beds and their bites were very painful." WEBER (1939) found live T. destructor in his luggage in Massachusetts several days after returning from Cuba by ship. Now, air travel, combined with the ant's propensity of nesting in electrical and electronic equipment, allows the possible spread of T. destructor to virtually anywhere in the world. For example, ENGST (2005) reported that, on arrival in New Zealand, an air passenger found T. destructor living inside a sealed iPod bought in the air-port in Fiji.

I found many reports of T. destructor destroying property and attacking people. For example, STONEY (1995) wrote that in Western Australia, T. destructor "has been known to chomp through a grown man's thong overnight and chew up anything from polystyrene cups to wiring in cars, telephones and houses... The insect has even nibbled on newborn babies sleeping in their cots and left big holes in car tyres. 'Kids are virtually being eaten alive while they sleep at night,' the Derby shire president, Mr. Peter McCumstie, said." CHIN (1998) wrote how in Darwin, Australia, T. destructor "can cause havoc in the household since they bite and may occur almost everywhere inside the house, feeding on a wide variety of food materials. They frequently nest in power sockets and chew on electrical wiring and in some cases have started electrical fires." In the community of Nguiu on Bathurst Island, Australia, B. Hoffmann investigated an enormous outbreak of T. destructor (CSIRO 2003). Hoffmann reported, "The magnitude of damage is really overwhelming… There were massive trails going into houses from all directions – millions and millions of Singapore ants [T. destructor] swarming everywhere. These ants get into power points, they eat electrical wiring and short circuit the power – two houses have already burned down recently because of damage caused to electrical systems (ANONYMOUS 2003). On Tobi Island and Helen Reef Atoll in Palau, BOUDJELAS (2006) reported that T. destructor was a serious threat to essential infrastructure and "causes extensive economic damage in human settlements by damaging fabric and rubber goods and removing insulation from electric cables." LEE & al. (2002) found that in surveys of food preparation outlets on Penang Island, Malaysia, T. destructor was the dominant ant species, making up 27.8% of the ant specimens collected.

In the Dry Tortugas, the outermost of the Florida Keys, MAYOR (1922) reported that T. destructor on Loggerhead Key was "a great pest in the wooden buildings of Tortugas Laboratory, making its nests in crevices of the woodwork. So voracious are these insects that we are obliged to swing our beds from the rafters and to paint the ropes with a solution of corrosive sublimate, while all tables must have tape soaked in corrosive sublimate wrapped around their legs if ants are to be excluded from them. These pests have the habit of biting out small pieces of skin, and I have seen them kill within 24 hours rats which were confined in cages." At Tortugas Laboratory, "one of the scientists, a newcomer who allowed his sheet to touch the floor, was stung so badly by a swarm of them that he lapsed into unconsciousness for a while" (STEPHENS & CALDER 2006). The Tortugas Laboratory buildings were later abandoned and torn down. Remarkably, no subsequent collector found T. destructor on Loggerhead Key (WETTERER & O'HARA 2002). Elsewhere in the Florida Keys, DEYRUP (1991) wrote that T. destructor "is spectacularly common on Key West." In a recent visit to Key West, however, I was unable to find any T. destructor. Instead, all areas where I collected on Key West were dominated by Pheidole megacephala and/or Solenopsis invicta (J.K. Wetterer, unpubl.).

Trichomyrmex destructor populations appear to be expanding in the West Indies, where they are a serious household problem. For example, in my apartment in Tunapuna, Trinidad, enormous trails of T. destructor foragers streamed out of an electrical socket and into the cupboards, trashcan, and kitchen sink, carrying off any scrap of food they could find. In an electronics store in Aripo, Trinidad, the owners reported this species nesting inside their computers. In a hotel room in Grand Anse, Grenada, a large trail of T. destructor emerged out of the air-conditioner to forage in my trashcan. In addition to urban areas, I also found T. destructor swarming down trees in parks and disturbed forests, for example in beachfront parks on Grenada, St. Croix, St. Vincent, and St. Lucia and in a forest of the poisonous manchineel tree (Hippomane mancinella LINNAEUS, 1753) on Curaçao.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis craccivora (a trophobiont) (Shiran et al., 2013; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis frangulae (a trophobiont) (Shiran et al., 2013; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Aphis nerii (a trophobiont) (Stary, 1969; Saddiqui et al., 2019) (as Monomorium gracillimum).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Chaitophorus euphraticus (a trophobiont) (Shiran et al., 2013; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Uroleucon dactynotus (a trophobiont) (Stary, 1969; Saddiqui et al., 2019) (as Monomorium gracillimum).

- This species is a host for the cestode Cotugnia digonopora (a parasitoid) (Quevillon, 2018) (encounter mode secondary; indirect transmission; transmission outside nest).

- The beetle species Thorictus bengalensis (Dermestidae: Thorictinae: Thorictini) resides as a nest associate of this ant, but details of their relationship are unknown (Háva et al. 2024).

Castes

Worker

Workers are polymorphic.

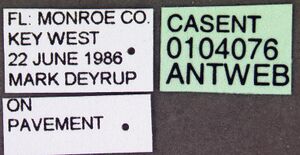

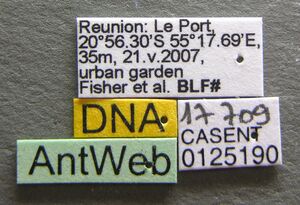

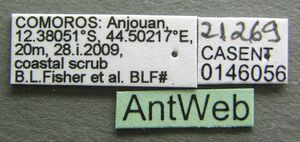

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0073621. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0101473. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MNHN, Paris, France. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0101474. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MNHN, Paris, France. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0104076. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0125190. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0146056. Photographer Erin Prado, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0173269. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CDRS, Galapagos, Ecuador. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0481865. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0481867. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0010944. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Queen

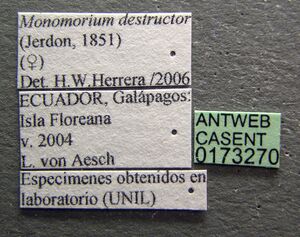

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0173270. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CDRS, Galapagos, Ecuador. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0173271. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CDRS, Galapagos, Ecuador. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- destructor. Atta destructor Jerdon, 1851: 105 (w.) INDIA (no state data).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: India: (no further data) “common in all parts of India…very destructive and troublesome to the naturalist” (T.C. Jerdon).

- Type-depository: no type-material known to exist.

- [Note: Sharaf, Salman, et al. 2016a: 16, accidentaly refer to the lectotype of vexator as the lectotype of destructor.]

- [Duplicated in Jerdon, 1854a: 47.]

- [Misspelled as destructa by Smith, F. 1858b: 163; misspelled as decstructor by Menozzi, 1929a: 4.]

- Bingham, 1903: 209 (q.m.).

- Combination in Monomorium: Emery, in Dalla Torre, 1893: 66;

- combination in M. (Parholcomyrmex): Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874;

- combination in Trichomyrmex: Ward, et al. 2015: 76.

- Status as species: Smith, F. 1858b: 163; Mayr, 1863: 396; Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Emery, 1893c: 82; Emery, 1893f: 243, 256; Emery, 1893g: 263; Forel, 1895b: 125; Mayr, 1897: 427; Emery, 1901f: 117; Emery, 1901g: 567; Forel, 1903a: 687; Bingham, 1903: 209; Forel, 1903d: 404; Forel, 1904b: 373; Wheeler, W.M. 1905b: 123; Forel, 1907a: 19; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1908h: 671; Santschi, 1908: 517; Forel, 1909e: 394; Wheeler, W.M. 1909d: 334, 339; Forel, 1910b: 29; Yano, 1910: 419; Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 562; Wheeler, W.M. 1911a: 22; Forel, 1911d: 380; Forel, 1911i: 221; Forel, 1912a: 55; Forel, 1912d: 105; Forel, 1912g: 3; Wheeler, W.M. 1912a: 45; Forel, 1913f: 191; Forel, 1913k: 53; Wheeler, W.M. 1913d: 240; Forel, 1915b: 73; Donisthorpe, 1915d: 336; Arnold, 1916: 235; Santschi, 1921b: 424; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Wheeler, W.M. 1923c: 4; Essig, 1926: 858; Stärcke, 1926: 86 (in key); Wheeler, W.M. 1927d: 5; Wheeler, W.M. 1927g: 108; Borgmeier, 1927c: 99; Donisthorpe, 1927b: 387; Wheeler, W.M. 1928c: 19; Menozzi, 1929a: 4; Wheeler, W.M. 1929g: 61; Wheeler, W.M. 1930a: 100; Wheeler, W.M. 1930h: 67; Menozzi & Russo, 1930: 158; Aguayo, 1932: 217; Kutter, 1932: 207; Mukerjee, 1934: 7; Wheeler, W.M. 1934h: 13; Donisthorpe, 1935: 633; Wheeler, W.M. 1935g: 25; Wheeler, W.M. 1936f: 10; Smith, M.R. 1937: 833; Finzi, 1939a: 164; Teranishi, 1940: 57; Eidmann, 1942: 248; Kusnezov, 1949a: 425; Creighton, 1950a: 224; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 811; Chapman & Capco, 1951: 166; Wellenius, 1955: 8; Wilson, 1962c: 16; Wilson, 1964b: 7; Baltazar, 1966: 259; Ettershank, 1966: 88; Smith, M.R. 1967: 357; Wilson & Taylor, 1967: 64; Taylor, 1967b: 1094; Kempf, 1972a: 143; Alayo, 1974: 14 (in key); Taylor, 1976a: 86; Báez & Ortega, 1978: 190; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1382; Barquin Diez, 1981: 204; Collingwood, 1985: 270; Bolton, 1987: 324 (redescription); Taylor, 1987a: 40; Deyrup, et al. 1989: 96; Brandão, 1991: 357; Ogata, 1991b: 107; Wu, J. & Wang, 1992: 1307; Morisita, et al. 1992: 39; Dlussky, 1994: 54; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Wu, J. & Wang, 1995: 89; Dorow, 1996a: 78; Collingwood & Agosti, 1996: 346; Collingwood, Tigar & Agosti, 1997: 508; Tiwari, 1999: 57; Deyrup, et al. 2000: 297; Deyrup, 2003: 45; Imai, et al. 2003: 134; Lin & Wu, 2003: 66; Wetterer & Vargo, 2003: 417; Collingwood, et al. 2004: 484; Ghosh, et al. 2005: 26; Jaitrong & Nabhitabhata, 2005: 27; Heterick, 2006: 96 (redescription); Wetterer, 2006: 415; Fernández, 2007b: 134; Clouse, 2007b: 247; Framenau & Thomas, 2008: 68; Paknia, et al. 2008: 155; Heterick, 2009: 164; Terayama, 2009: 153; Vonshak, et al. 2009: 43; Wetterer, 2009c: 97; Mohanraj, et al. 2010: 6; Collingwood, et al. 2011: 433; Guénard & Dunn, 2012: 45; Sarnat & Economo, 2012: 87; Hita Garcia, et al. 2013: 212; Sarnat, et al. 2013: 71; Borowiec, L. 2014: 118; Ramage, 2014: 164; Bharti, Guénard, et al. 2016: 47; Jaitrong, Guénard, et al. 2016: 40; Wetterer, et al. 2016: 21; Sharaf, Salman, et al. 2016a: 16 (redescription); Sharaf, Fisher, et al. 2017: 47; Deyrup, 2017: 72; Dekoninck, et al. 2019: 1159; Fernández & Serna, 2019: 828; Lubertazzi, 2019: 196; Borowiec, L. & Salata, 2020: 19; Dias, R.K.S. et al. 2020: 99; Sharaf, Abdel-Dayem, et al. 2020: 552.

- Senior synonym of atomaria: Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- Senior synonym of basalis: Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Forel, 1894b: 86; Forel, 1895b: 125; Forel, 1903a: 687; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Creighton, 1950a: 224; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1382; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Tiwari, 1999: 57; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- Senior synonym of gracillima: Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Dorow, 1996a: 78; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- Senior synonym of ominosa: Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- Senior synonym of vexator: Donisthorpe, 1932c: 468; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Heterick, 2006: 97.

- Distribution [tramp species]:

- Afrotropical: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, Niger, South Africa, Sudan.

- Austral: Australia, New Zealand.

- Malagasy: Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Réunion, Seychelles.

- Malesian: Cook Is, Fiji Is, French Polynesia, Gilbert Is, Hawaii Is, Indonesia (Flores, Ternate), Kiribati, Malaysia, Marshall Is, Micronesia, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines (Luzon), Samoa, Singapore, Solomon Is.

- Nearctic: U.S.A.

- Neotropical: Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Ecuador (+ Galapagos Is), Grenada, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles (Aruba), Puerto Rico, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent & the Grenadines, Trinidad, Venezuela, Virgin Is.

- Oriental: Bangladesh, China, Christmas I., India (+ Andaman Is), Japan, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam.

- Palaearctic: Afghanistan, Algeria, Cape Verde, Cyprus, Egypt, Great Britain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Spain (+ Canary Is), Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Yemen.

- atomaria. Myrmica atomaria Gerstäcker, 1859: 263 (w.) (no state data).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: Mozambique: (no further data) (Peters).

- Type-depository: unknown, possibly MNHU.

- [Also described as new by Gerstäcker, 1862: 518; type-locality Mozambique from this reference.]

- Combination in Monomorium: Roger, 1863b: 31; Mayr, 1863: 429.

- Status as species: Mayr, 1863: 429.

- Junior synonym of ominosa: Roger, 1863b: 31.

- Junior synonym of destructor: Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- basalis. Myrmica basalis Smith, F. 1858b: 125 (w.) SRI LANKA.

- Type-material: lectotype worker (by designation of Heterick, 2006: 97), 2 paralectotype workers.

- Type-locality: lectotype Sri Lanka (“Ceylon”): (no further data); paralectotypes with same data.

- Type-depository: BMNH.

- Combination in Monomorium: Mayr, 1865: 92.

- Status as species: Mayr, 1863: 431; Motschoulsky, 1863: 15; Mayr, 1865: 92; Smith, F. 1871a: 327; Emery, 1877b: 369; Emery, 1881b: 532 (in key); Mayr, 1886c: 359; André, 1893b: 152.

- Junior synonym of destructor: Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Forel, 1894b: 86; Forel, 1895b: 125; Forel, 1903a: 687; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Creighton, 1950a: 224; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1382; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 259; Tiwari, 1999: 57; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- gracillima. Myrmica gracillima Smith, F. 1861a: 34 (w.) (no state data).

- Type-material: holotype worker.

- Type-locality: Israel: (no further data) (J.D. Hooker & D. Hanbury).

- Type-depository: holotype lost (not in BMNH or OXUM).

- [Misspelled as gracillium by Chapman & Capco, 1951: 166.]

- Emery, 1877b: 369 (footnote) (q.m.).

- Combination in Monomorium: Mayr, 1862: 753;

- combination in M. (Holcomyrmex): Santschi, 1914d: 354;

- combination in M. (Parholcomyrmex): Emery, 1915i: 190.

- Status as species: Mayr, 1862: 753; Roger, 1863b: 32; Mayr, 1863: 429; Emery, 1877b: 369 (footnote); Mayr, 1877: 20 (in list); Emery, 1881b: 533; André, 1881b: 68; André, 1883a: 333 (in key); André, 1884b: 541; Emery, 1889b: 503; Dalla Torre, 1893: 67; Forel, 1894b: 88; Emery, 1895k: 465; Forel, 1902a: 152; Forel, 1903a: 687; Bingham, 1903: 210; Forel, 1904c: 25; Ruzsky, 1905b: 635; Forel, 1907a: 19; Mayr, 1907b: 12; Emery, 1908h: 669; Santschi, 1908: 518; Forel, 1909e: 381, 394; Wheeler, W.M. 1909d: 339; Karavaiev, 1910b: 57; Karavaiev, 1911: 4; Viehmeyer, 1914a: 113; Santschi, 1914d: 354; Crawley, 1920a: 165; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 163, 874, 1027; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1923b: 3; Ruzsky, 1923: 4; Santschi, 1924c: 99; Santschi, 1929c: 100; Menozzi, 1932c: 95; Menozzi, 1933b: 63; Menozzi, 1934: 155; Santschi, 1934f: 168; Wheeler, W.M. 1934h: 14; Wheeler, W.M. 1935g: 25; Finzi, 1936: 178; Finzi, 1939a: 158; Santschi, 1938a: 39; Santschi, 1939d: 74; Donisthorpe, 1942a: 29; Bernard, 1948: 143; Chapman & Capco, 1951: 166; Bernard, 1953a: 168; Délye, 1960: 266; Collingwood, 1961a: 62; Collingwood, 1962: 225; Baltazar, 1966: 260; Ettershank, 1966: 89; Pisarski, 1967: 399; Wilson & Taylor, 1967: 66; Hamann & Klemm, 1967: 414; Pisarski, 1970: 309; Bernard, 1971: 7; Dlussky, 1981a: 17; Collingwood, 1985: 270; Kugler, J. 1988: 258; Dlussky, Soyunov & Zabelin, 1990: 235; Tohmé, G. & Tohmé, 2014: 135 (error).

- Subspecies of destructor: Forel, 1913d: 437; Viehmeyer, 1923: 91.

- Junior synonym of destructor: Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 261; Dorow, 1996a: 78; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- ominosa. Myrmica ominosa Gerstäcker, 1859: 263 (w.) (no state data).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: Mozambique: (no further data) (Peters).

- Type-depository: unknown, perhaps MNHU.

- [Also described as new by Gerstäcker, 1862: 517; type-locality Mozambique from this reference.]

- Combination in Monomorium: Roger, 1863b: 31.

- Status as species: Roger, 1863b: 31; Mayr, 1863: 429.

- Junior synonym of destructor: Dalla Torre, 1893: 66; Wheeler, W.M. 1908a: 126; Emery, 1922e: 180; Wheeler, W.M. 1922a: 874; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 265; Heterick, 2006: 96.

- vexator. Myrmica vexator Smith, F. 1861b: 47 (w.) INDONESIA (Ternate I.).

- Type-material: lectotype worker (by designation of Heterick, 2006: 97), 2 paralectotype workers.

- Type-locality: lectotype Indonesia: Ternate I., “Ter.21” (A.R. Wallace), paralectotypes with same data.

- Type-depository: OXUM.

- [Unjustified emendation of spelling to vexatrix: Schulz, W.A. 1906: 155.]

- Status as species: Mayr, 1863: 436; Smith, F. 1871a: 326; Dalla Torre, 1893: 118; Chapman & Capco, 1951: 131.

- Junior synonym of destructor: Donisthorpe, 1932c: 468; Bolton, 1987: 324; Bolton, 1995b: 268; Heterick, 2006: 97.

Type Material

- Atta destructor Jerdon, 1851: Syntype, worker(s), India, India.

The following notes on F. Smith type specimens have been provided by Barry Bolton (details):

Myrmica vexator

Three worker syntypes in Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Labelled “Ter. 21.” (= Ternate I.)

Description

Worker

Heterick (2006) - HEAD: Head square; vertex planar or weakly concave; frons longitudinally finely striolate anteriad (striolae curving inwards around antennal insertions), smooth and shining posteriad, except for a few transverse rugulae on upper vertex; pilosity of frons consisting mainly of appressed and decumbent setulae with a few erect setae on vertex. Eye large, eye width 1.5× greater than greatest width of antennal scape to moderate, eye width 1–1.5× greatest width of antennal scape; (in full-face view) eyes set below midpoint of head capsule; (viewed in profile) eyes set around midline of head capsule; eye elliptical, curvature of inner eye margin may be more pronounced than that of its outer margin. Antennal segments 12; antennal club three-segmented. Clypeal carinae indicated by multiple weak ridges; anteromedian clypeal margin broadly convex to straight; paraclypeal setae moderately long and fine, curved; posteromedian clypeal margin extending slightly beyond level of posterior margin of antennal fossae. Anterior tentorial pits situated nearer antennal fossae than mandibular insertions. Frontal lobes sinuate, divergent posteriad. Weak psammophore present. Palp formula 2,2. Mandibular teeth three, plus minute, basal denticle or angle; mandibles with sub-parallel inner and outer margins, striate; masticatory margin of mandibles approximately vertical or weakly oblique; basal tooth a small to minute denticle or angle, much smaller than t3 (four teeth present).

MESOSOMA: Promesonotum shining and smooth on dorsum, lower mesopleuron strongly punctate; (viewed in profile) promesonotum broadly convex anteriad, convexity reduced posteriad; promesonotal setae seven to twelve; standing promesonotal setae a mixture of well-spaced, distinctly longer, erect and semi-erect setae which are curved distally and often paired, interspersed with much shorter, incurved, decumbent setae; appressed promesonotal setulae well-spaced over entire promesonotum. Metanotal groove strongly impressed, with distinct transverse costulae. Propodeum uniformly finely striolate, some punctation on metapleuron; propodeal dorsum flat throughout most of its length; propodeum smoothly rounded or with indistinct angle; standing propodeal setae variable in number and arrangement, when present usually one prominent pair at propodeal angles or at midlength, with other shorter setae very sparse or absent; appressed propodeal setulae well-spaced and sparse; propodeal spiracle equidistant from metanotal groove and declivitous face of propodeum. Vestibule of propodeal spiracle distinct in some specimens. Propodeal lobes present as vestigial flanges or small strips of cuticle only.

PETIOLE AND POSTPETIOLE: Petiolar spiracle lateral or laterodorsal and situated within anterior sector of petiolar node or just at front of node; node (viewed in profile) conical, vertex rounded; appearance of node shining and smooth throughout; ratio of greatest node breadth (viewed from front) to greatest node width (viewed in profile) between 1:1 and 3:4; anteroventral petiolar process absent or vestigial; ventral petiolar lobe absent; height ratio of petiole to postpetiole between 1:1 and 3:4; height–length ratio of postpetiole between 4:3 and 3:4; postpetiole shining and smooth; postpetiolar sternite without anterior lip or carina, or this structure vestigial.

GASTER: Pilosity of first gastral tergite consisting of well-spaced, erect and semi-erect setae interspersed with a few appressed setulae.

MESOSOMA: Color yellow-orange to brownish-orange, gaster chocolate with or without yellowish area on anterior sector of first gastral tergite. Worker caste monophasically allometric, i.e., with variable size, but not morphology among workers from same nest.

LECTOTYPE MEASUREMENTS (M. basale): HML 1.70 HL 0.66 HW 0.58 CeI 88 SL 0.48 SI 83 PW 0.34.

LECTOTYPE MEASUREMENTS (M. vexator): HML 1.78 HL 0.68 HW 0.62 CeI 91 SL 0.50 SI 81 PW 0.36.

OTHER WORKER MEASUREMENTS (non-types): HML 1.31–1.92 HL 0.49–0.76 HW 0.38–0.68 CeI 78–89 SL 0.39–0.52 SI 76–103 PW 0.25–0.40 (n=20).

Sharaf et al. (2016) - Small workers TL 1.79–2.33; HL 0.47–0.64; HW 0.38–0.45; SL 0.38–0.45; EL 0.07; ML 0.50–0.64;PW 0.23–0.28; PTL 0.14–0.20; PTW 0.07–0.11; PPL 0.10–0.16; PPW 0.08–0.13; CI 71–85; EI 15–18; SI 88–111 (n = 10). Worker. TL 1.80–3.50; HL 0.50–0.88; HW 0.40–0.79; SL 0.41–0.56; PW 0.23–0.45; ML 0.54–0.92; CI 76–92; SI 70–104 (Bolton 1987).

Workers of this species exhibit size variation in any nest series.

Worker Head. Mandibles with three strong teeth, the fourth (basal) reduced to a minute offset denticle; eyes relatively small (EL 0.14–0.20 × HW), with 4–6 ommatidia in longest row; in small workers scapes relatively long (SI 88–111), when laid back from their insertions reaching posterior margin of head; in large workers scapes relatively shorter (SI 70–104), failing to reach posterior margin of head.

Mesosoma. Promesonotum convex in profile; metanotal groove impressed.

Petiole. Petiolar node rounded in profile.

Postpetiole. Postpetiolar node lower than petiolar node in profile.

Pilosity. Posterior margin of head with 2–4 pairs of hairs; cephalic surface behind frontal lobes with 1–4 pairs of hairs straddling midline; cephalic pubescence scattered and directed inward to midline; promesonotal dorsum and propodeum with many pairs of long hairs; petiole, postpetiole and gaster with backward directed long hairs.

Sculpture. Cephalic surface smooth and shining, except areas in front of eyes and posterior margin of head (in dorsal view) finely striolate; mandibles longitudinally striolate; promesonotum and mesonotum smooth and shining; mesopleura densely punctulate-reticulate; propodeal dorsum finely transversely striolate to rugulose, fainter in smaller than in larger workers; gastral tergite smooth and shining.

Colour. Head, mesosoma, petiole and postpetiole ranging from pale yellow to dull brownish yellow; gaster dark brown to blackish brown, with a distinct yellowish area mediobasally.

Queen

Heterick (2006) - HEAD: Head rectangular; vertex weakly concave or planar; frons shining and smooth except for piliferous pits and striolae around antennal sockets, frontal carinae and below the eyes, and fine rugulae near posterior margin of vertex; frons consisting mainly of decumbent setae, with two longitudinal, parallel rows of erect setae straddling the midline. Eye elongate, elliptical and oblique; (in full-face view) eyes set above midpoint of head capsule; (viewed in profile) eyes set posteriad of midline of head capsule.

MESOSOMA: Anterior mesoscutum smoothly rounded, thereafter more-or-less flattened; pronotum, mesoscutum and mesopleuron shining and mainly smooth, vestigial striolae, if present, confined to anterior katepisternum; length–width ratio of mesoscutum and scutellum combined between 7:3 and 2:1. Axillae a strip of thin cuticle separating mesoscutum and scutellum, each individual axilla indistinct. Standing pronotal/mesoscutal setae a mixture of well-spaced, distinctly longer, erect and semi-erect setae which are curved distally, interspersed with much shorter, incurved, decumbent setae; appressed pronotal, mescoscutal and mesopleural setulae abundant, particularly on mesoscutum. Propodeum shining and smooth, with a few weak striolae on metapleuron; always smoothly rounded; propodeal dorsum convex; standing propodeal setae consisting of one pair anteriad, with or without another pair posteriad; propodeal spiracle nearer metanotal groove than declivitous face of propodeum; propodeal lobes present as vestigial flanges only, or absent.

WING: Wing not seen (queen dealated).

PETIOLE AND POSTPETIOLE: Petiolar spiracle lateral and situated slightly anteriad of petiolar node; (viewed in profile) node conical, vertex rounded; appearance of node shining and smooth; ratio of greatest node breadth (viewed from front) to greatest node width (viewed in profile) about 1:1. Anteroventral petiolar process absent or vestigial; height ratio of petiole to postpetiole between 4:3 and 1:1; height–length ratio of postpetiole between 4:3 and 1:1; postpetiole shining, with vestigial sculpture; postpetiolar sternite with anterior and posterior margins convergent, forming a narrow wedge.

GASTER: Pilosity of first gastral tergite consisting mainly of appressed setae with a few erect and semi-erect setae.

GENERAL CHARACTERS: Color of foreparts tawny-yellow, gaster brown. Brachypterous alates not seen. Ergatoid or worker-female intercastes not seen.

QUEEN MEASUREMENTS: HML 3.22–3.46 HL 0.83–0.84 HW 0.76–0.80 CeI 92–95 SL 0.60–0.62 SI 78 PW 0.68–0.89 (n=2).

Type Material

Heterick 2006:

- Atta destructor Jerdon 1851:105. Syntype workers, INDIA [no types known to exist].

- Myrmica basalis Smith 1858:125. Syntype worker (lectotype here designated), SRI LANKA (The Natural History Museum) [examined].

References

- Abdar, M.R. 2020. Seasonal abundance and commonly occurring household ants species in Sangli District Maharashtra. Research Journal of Agricultural Sciences 11(6): 1413-1415.

- Baidya, P., Bagchi, S. 2021. Influence of human land use and invasive species on beta diversity of tropical ant assemblages. Insect Conservation and Diversity, icad.12536 (doi:10.1111/icad.12536).

- Baltazar, C.R. 1966. A catalogue of Philippine Hymenoptera (with a bibliography, 1758-1963). Pacific Insects Monographs 8: 1-488. (page 259, listed)

- Bingham, C. T. 1903. The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Hymenoptera, Vol. II. Ants and Cuckoo-wasps. London: Taylor and Francis, 506 pp. (page 209, queen, male described)

- Bolton, B. 1987. A review of the Solenopsis genus-group and revision of Afrotropical Monomorium Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bull. Br. Mus. (Nat. Hist.) Entomol. 54: 263-452 (page 324, Senior synonym of gracillima)

- Borowiec, L., Salata, S. 2019. Next step in the invasion: Trichomyrmex mayri (Forel, 1902) new to the Philippines (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Upper Silesian Museum in Bytom Entomology 28:1-3 (doi:10.5281/ZENODO.2644912).

- Borowiec, L., Salata, S. 2020. Review of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Jordan. Annals of the Upper Silesian Museum in Bytom, Entomology 29 (online 2): 1-26 (doi:10.5281/zenodo.3733156).

- Casiraghi, A., Espadaler, X., Pérez Hidalgo, N., Gómez, K. 2020. Two additions to the Iberian myrmecofauna: Crematogaster inermis Mayr, 1862, a newly established, tree-nesting species, and Trichomyrmex mayri (Forel, 1902), an emerging exotic species temporarily nesting in Spain (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research 78, 57–68 (doi:10.3897/jhr.78.51858).

- Collingwood, C. A., Pohl, H., Guesten, R., Wranik, W. and van Harten, A. 2004. The ants (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Socotra Archipelago. Fauna of Arabia. 20:473-495.

- Collingwood, C.A., Agosti, D., Sharaf, M.R., van Harten, A. 2011. Order Hymenoptera, family Formicidae. Arthropod fauna of the UAE 4: 405-474.

- Dalla Torre, K. W. von. 1893. Catalogus Hymenopterorum hucusque descriptorum systematicus et synonymicus. Vol. 7. Formicidae (Heterogyna). Leipzig: W. Engelmann, 289 pp. (page 66, Combination in Monomorium, Senior synonym of ominosa (and its junior synonym atomaria))

- Dekoninck, W., Wauters, N., Delsinne, T. 2019. Capitulo 35. Hormigas invasoras en Colombia. Hormigas de Colombia.

- Dendup, K.C., Dorji, C., Dhadwal, T., Bharti, H., Pfeiffer, M. 2021. A preliminary checklist of ants from Bhutan. Asian Myrmecology 14, e014005 (doi:10.20362/am.014005).

- Dey, M.K., Hazra, A.K. 2021. Abundance of microarthropods population in different sites of Midnapore east coast of West Bengal, India. International Journal of Advancement in Life Sciences Research 4: 13-25 (doi:10.31632/ijalsr.2021.v04i03.003).

- Deyrup, M.A., Carlin, N., Trager, J., Umphrey, G. 1988. A review of the ants of the Florida Keys. Florida Entomologist 71: 163-176.

- Dias, R.K.S., Kosgamage, K.R.K.A. 2013. Occurrence and species diversity of ground-dwelling worker ants (Family: Formicidae) in selected lands in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. Journal of Science of the University of Kelaniya Sri Lanka 7: 55-72 (doi:10.4038/josuk.v7i0.6233).

- Dias, R.K.S., Rajapaksa, R.P.K.C. 2017. Geographic records of subfamilies, genera and species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the four climatic zones of Sri Lanka: A review. Journal of Science of the University of Kelaniya Sri Lanka 11, 23-45. (doi:10.4038/josuk.v11i2.7999).

- Donisthorpe, H. 1932c. On the identity of Smith's types of Formicidae (Hymenoptera) collected by Alfred Russell Wallace in the Malay Archipelago, with descriptions of two new species. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 10(10): 441-476 (page 468, Senior synonym of vexator)

- Fontenla, J.L., Brito, Y.M. 2011. Hormigas invasoras y vagabundas de Cuba. Fitosanidad 15(4), 253-259.

- Forel, A. 1894b. Abessinische und andere afrikanische Ameisen, gesammelt von Herrn Ingenieur Alfred Ilg, von Herrn Dr. Liengme, von Herrn Pfarrer Missionar P. Berthoud, Herrn Dr. Arth. Müller etc. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 9: 64-100 (page 86, Senior synonym of basalis)

- Hasin, S., Tasen, W. 2020. Ant community composition in urban areas of Bangkok, Thailand. Agriculture and Natural Resources 54: 507-514 (doi:10.34044/j.anres.2020.54.5.07).

- Háva, J., Chakrovorty, A., Bhattacharjee, B. & Samadder, A. 2024. Thorictus bengalensis sp. nov., a new species of myrmecophylous beetle from India, West Bengal (Coleoptera: Dermestidae: Thorictinae: Thorictini). Studies and Reports, Taxonomical Series, 20 (1).

- Herrera, H.W., Baert, L., Dekoninck, W., Causton, C.E., Sevilla, C.R., Pozo, P., Hendrickx, F. 2020. Distribution and habitat preferences of Galápagos ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Belgian Journal of Entomology, 93: 1–60.

- Heterick, B. E. 2006. A revision of the Malagasy ants belonging to genus Monomorium Mayr, 1855 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 57:69-202.

- Heterick, B.E. 2021. A guide to the ants of Western Australia. Part I: Systematics. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 86, 1-245 (doi:10.18195/issn.0313-122x.86.2021.001-245).

- Heterick, B.E. 2022. A guide to the ants of Western Australia. Part II: Distribution and biology. Records of the Western Australian Museum, supplement 86: 247-510 (doi:10.18195/issn.0313-122x.86.2022.247-510).

- Hosoishi, S., Rahman, M. M., Heng, S. 2022. Exotic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Cambodia. Far Eastern Entomologist 460, 15–24 (doi:10.25221/fee.460.3).

- Jerdon, T. C. 1851. A catalogue of the species of ants found in Southern India. Madras J. Lit. Sci. 17: 103-127 (page 105, worker described)

- Karaman, C., Kıran, K. 2018. New tramp ant species for Turkey: Tetramorium lanuginosum Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Trakya University Journal of Natural Sciences 19(1), e1-e4 (doi:10.23902/trkjnat.340008).

- Khachonpisitsak, S., Yamane, S., Sriwichai, P., Jaitrong, W. 2020. An updated checklist of the ants of Thailand (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 998, 1–182 (doi:10.3897/zookeys.998.54902).

- Lee, C.-C., Weng, Y.-M., Lai, L.-C., Suarez, A.V., Wu, W.-J., Lin, C.-C., Yang, C.-C.S. 2020. Analysis of recent interception records reveals frequent transport of arboreal ants and potential predictors for ant invasion in Taiwan. Insects 11, 356 (doi:10.3390/INSECTS11060356).

- Lubertazzi, D. 2019. The ants of Hispaniola. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 162(2), 59-210 (doi:10.3099/mcz-43.1).

- Mamet, R. 1954. The ants (Hymenoptera Formicidae) of the Mascarene Islands. Mauritius Inst. Bull. 3: 249-259 (see also)

- Meurgey, F. 2020. Challenging the Wallacean shortfall: A total assessment of insect diversity on Guadeloupe (French West Indies), a checklist and bibliography. Insecta Mundi 786: 1–183.

- Mukherjee, A., Roy, U.S. 2021. Role of physicochemical parameters on diversity and abundance of ground–dwelling, diurnal ant species of Durgapur Government College Campus, West Bengal, India. Munis Entomology and Zoology Journal 16(1): 366-380.

- Oussalah, N., Marniche, F., Espadaler, X., Biche, M. 2019. Exotic ants from the Maghreb (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) with first report of the hairy alien ant Nylanderia jaegerskioeldi (Mayr) in Algeria. Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 45–58 (doi:10.32800/amz.2019.17.0045).

- Reyes, J.L. 2010. Apuntes sobre una comunidad de hormigas sinantrópicas en Santiago de Cuba (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Cocuyo 18: 44-47.

- Rosas-Mejía, M., Guénard, B., Aguilar-Méndez, M. J., Ghilardi, A., Vásquez-Bolaños, M., Economo, E. P., Janda, M. 2021. Alien ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Mexico: the first database of records. Biological Invasions 23(6), 1669–1680 (doi:10.1007/s10530-020-02423-1).

- Sharaf, M. R., Wetterer, J. K., Mohamed, A. A., Aldawood, A. S. 2022. Faunal composition, diversity, and distribution of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Dhofar Governorate, Oman, with updated list of the Omani species and remarks on zoogeography. European Journal of Taxonomy 838: 1-106 (doi:10.5852/ejt.2022.838.1925).

- Sharaf, M.R., Abdel-Dayem, M.S., Mohamed, A.A., Fisher, B.L., Aldawood, A.S. 2020. A preliminary synopsis of the ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Qatar with remarks on the zoogeography. Annales Zoologici 70: 533-560 (doi:10.3161/00034541anz2020.70.4.005).

- Sharaf, M.R., Fisher, B.L., Collingwood, C.A., Aldawood, A.S. 2017. Ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Socotra Archipelago (Yemen): zoogeography, distribution and description of a new species. Journal of Natural History 51, 317–378 (DOI 10.1080/00222933.2016.1271157).

- Sharaf, M.R., Salman, S., Al Dhafer, H.M., Akbar, S.A., Abdel-Dayem, M.S. & Aldawood, A.S. 2016. Taxonomy and distribution of the genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with the description of two new species. European Journal of Taxonomy 246:1-36 (doi:10.5852/ejt.2016.246).

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. i-xvi, 1199-2209. (page 1382, see also)

- Sparks, K. 2015. Australian Monomorium: Systematics and species delimitation with a focus of the M. rothsteini complex. Ph.D. thesis, University of Adelaide.

- Subedi, I.P., Budha, P.B., Bharti, H., Alonso, L. 2020. An updated checklist of Nepalese ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 1006, 99–136 (doi:10.3897/zookeys.1006.58808).

- Udayakantha, W.S., Dias, R.K.S., Rajapakse, R.P.K.C. 2023. Geographical records of six common ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in three climatic zones of Sri Lanka. Caucasian Entomological Bulletin 19(1), 71–78 (doi:10.23885/181433262023191-7178).

- Wang, W.Y., Soh, E.J.Y., Yong, G.W.J., Wong, M.K.L., Benoit Guénard, Economo, E.P., Yamane, S. 2022. Remarkable diversity in a little red dot: a comprehensive checklist of known ant species in Singapore (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with notes on ecology and taxonomy. Asian Myrmecology 15: e015006 (doi:10.20362/am.015006).

- Wetterer, J.K. 2009. Worldwide spread of the destroyer ant, Monomorium destructor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 12: 97-108.

- Wetterer, J.K. 2021. Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of St. Vincent, West Indies. Sociobiology 68, e6725 (doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v68i2.6725).

- Wheeler, W. M. 1922j. Ants of the American Museum Congo expedition. A contribution to the myrmecology of Africa. VIII. A synonymic list of the ants of the Ethiopian region. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 45: 711-1004 (page 874, Combination in M. (Parholcomyrmex))

- Wu, J. & Wang, C. 1992. Formicidae (pp. 1301-1320). In Peng, J. et al. Iconography of Forest Insects in Hunan, China. Forest Bureau of Hunan Province: 1473 pp. Hunan Scientific and Technical Publishing House.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Bharti H., Y. P. Sharma, M. Bharti, and M. Pfeiffer. 2013. Ant species richness, endemicity and functional groups, along an elevational gradient in the Himalayas. Asian Myrmecology 5: 79-101.

- Bhoje P. M., K. Shilpa, and T. V. Sathe. 2014. Diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Kolhapur district of Maharashtra, India. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 34(1): 23-25.

- Bolton B. 1987. A review of the Solenopsis genus-group and revision of Afrotropical Monomorium Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Entomology 54: 263-452.

- Chapman, J. W., and Capco, S. R. 1951. Check list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Asia. Monogr. Inst. Sci. Technol. Manila 1: 1-327

- Dias R. K. S. 2002. Current knowledge on ants of Sri Lanka. ANeT Newsletter 4: 17- 21.

- Dias R. K. S. 2006. Current taxonomic status of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Sri Lanka. The Fauna of Sri Lanka: 43-52. Bambaradeniya, C.N.B. (Editor), 2006. Fauna of Sri Lanka: Status of Taxonomy, Research and Conservation. The World Conservation Union, Colombo, Sri Lanka & Government of Sri Lanka. viii + 308pp.

- Dias R. K. S. 2013. Diversity and importance of soil-dweeling ants. Proceedings of the National Symposium on Soil Biodiversity, chapt 4, pp 19-22.

- Dias R. K. S., K. R. K. A. Kosgamage, and H. A. W. S. Peiris. 2012. The Taxonomy and Conservation Status of Ants (Order: Hymenoptera, Family: Formicidae) in Sri Lanka. In: The National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka; Conservation Status of the Fauna and Flora. Weerakoon, D.K. & S. Wijesundara Eds., Ministry of Environment, Colombo, Sri Lanka. p11-19.

- Dias R. K. S., and K. R. K. A. Kosgamage. Systematics and community composition of foraging workers ants (Family: Formicidae) collected from three habitats in a dry zone region of Sri Lanka. Proceedings of the Annual Research Symposium 2008. Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Kelaniya.

- Dias R. K. S., and K. R. K. Anuradha Kosgamage. 2012. Occurrence and species diversity of ground-dwelling worker ants (Family: Formicidae) in selected lands in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. J. Sci. Univ. Kelaniya 7: 55-72.

- Dias R. K. S., and R. P. K. C. Rajapaksa. 2016. Geographic records of subfamilies, genera and species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the four climatic zones of Sri Lanka: a review. J. Sci. Univ. Kelaniya 11(2): 23-45.

- Dias, R.K.S. 2006. Overview of ant research in Sri Lanka: 2000-2004. ANeT Newsletter 8:7-10

- Emery C. 1893. Voyage de M. E. Simon à l'île de Ceylan (janvier-février 1892). Formicides. Annales de la Société Entomologique de France 62: 239-258.

- Emery C. 1901. Ameisen gesammelt in Ceylon von Dr. W. Horn 1899. Deutsche Entomologische Zeitschrift 1901: 113-122.

- Forel A. 1903. Les fourmis des îles Andamans et Nicobares. Rapports de cette faune avec ses voisines. Rev. Suisse Zool. 11: 399-411.

- Forel A. 1907. Formicides du Musée National Hongrois. Ann. Hist.-Nat. Mus. Natl. Hung. 5: 1-42.

- Forel A. 1909. Études myrmécologiques en 1909. Fourmis de Barbarie et de Ceylan. Nidification des Polyrhachis. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 45: 369-407.

- Forel A. 1911. Ameisen aus Ceylon, gesammelt von Prof. K. Escherich (einige von Prof. E. Bugnion). Pp. 215-228 in: Escherich, K. Termitenleben auf Ceylon. Jena: Gustav Fischer, xxxii + 262 pp.

- Forel A. 1913k. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse einer Forschungsreise nach Ostindien ausgeführt im Auftrage der Kgl. Preuss. Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin von H. v. Buttel-Reepen. II. Ameisen aus Sumatra, Java, Malacca und Ceylon. Gesammelt von Herrn Prof. Dr. v. Buttel-Reepen in den Jahren 1911-1912. Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 36:1-148.

- Ghosh S. N., S. Sheela, and B. G. Kundu. 2005. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Rabindra Sarovar, Kolkata. Records of the Zoological Survey of India. Occasional Paper 234: 1-40.

- Gunawardene N. R., J. D. Majer, and J. P. Edirisinghe. 2008. Diversity and richness of ant species in a lowland wet forest reserve in Sri Lanka. Asian Myrmecology 2: 71-83.

- Gunawardene N. R., J. D. Majer, and J. P. Edirisinghe. 2012. Correlates of ant 5Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and tree species diversity in Sri Lanka. Myrmecological News 17: 81-90.

- Kosgamage K. R. K. A., and R. K. S. Dias 2008. Systematics and community composition of Foraging worker ants ((Order: Hymenoptera, Family: Formicidae) collected from three habitats on a dry zone region of Sri Lanka.Proceedings of Postgraduate Symposium of Kelaniya University. 115pp.

- Mohanraj P., M. Ali, and K. Veerakumari. 2010. Formicidae of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Indian Ocean: Bay of Bengal). Journal of Insect Science 10: Article 172

- Mohanraj, P., M. Ali and K. Veenakumari. 2010. Formicidae of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Indian Ocean: Bay Of Bengal). Journal of Insect Science 10:172.

- Narendra A., H. Gibb, and T. M. Ali. 2011. Structure of ant assemblages in Western Ghats, India: role of habitat, disturbance and introduced species. Insect Conservation and diversity 4(2): 132-141.

- Raci N., C. Sravanthy, C. Sammaiah, and M. Thirupahaiah. 2015. Biodiversity of ants (Insecta-Hymenoptera) in agroecosystem and grass land in Jammikunta, Karimnagar District, Telangana, India. Journal ofEnvironment 4(1): 11-16.

- Rajan P. D., M. Zacharias, and T. M. Mustak Ali. 2006. Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae. Fauna of Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple Wildlife Sanctuary (Karnataka). Conservation Area Series, Zool. Surv. India.i-iv,27: 153-188.

- Tak N. 2009. Ants Formicidae of Rajasthan. Records of the Zoological Survey of India, Occasional Paper No. 288, iv, 46 p

- Tak N., and N. S. Rathore. 2004. Insecta: Hymenoptera. Rathore, N.S. Fauna of Desert National Park Rajasthan (proposed biosphere reserve). Conservation Area Series 19,Zool. Surv. India. 1-135. Chapter pagination: 81-84.

- Tak N., and N. S. Rathore. 2004. Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae. State Fauna Series 8: Fauna of Gujarat. Zool. Surv. India. Pp. 161-183.

- Tak N., and S. L. Kazmi. 2011. On a collection of Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae from Uttarakhand. Rec. zool. Surv. India : 111(2) : 39-49.

- Varghese T. 2004. Taxonomic studies on ant genera of the Indian Institute of Science campus with notes on their nesting habits. Pp. 485-502 in : Rajmohana, K.; Sudheer, K.; Girish Kumar, P.; Santhosh, S. (eds.) 2004. Perspectives on biosystematics and biodiversity. Prof. T.C. Narendran commemoration volume. Kerala: Systematic Entomology Research Scholars Association, xxii + 666 pp.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- Highly invasive

- Supercolonies

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Aphis craccivora

- Host of Aphis frangulae

- Host of Aphis nerii

- Host of Chaitophorus euphraticus

- Host of Uroleucon dactynotus

- Cestode Associate

- Host of Cotugnia digonopora

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Crematogastrini

- Trichomyrmex

- Trichomyrmex destructor

- Myrmicinae species

- Crematogastrini species

- Trichomyrmex species

- Ssr