Pogonomyrmex badius

| Pogonomyrmex badius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Pogonomyrmecini |

| Genus: | Pogonomyrmex |

| Species group: | californicus |

| Species: | P. badius |

| Binomial name | |

| Pogonomyrmex badius (Latreille, 1802) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Florida Harvester Ant | |

| Language: | English |

Unusual within the genus for its distribution - it is the only species found in the eastern United States - and its polymorphic workers.

Photo Gallery

Identification

The minor worker of badius, which is the dominant subcaste, can readily be distinguished from the worker of all other species of North American Pogonomyrmex by the head shape, which is rather strongly narrowed posteriorly in full-face view, the conformation of the scape base, and the small eyes which are placed distinctly beneath the middle of the sides of the head. The major workers, as well as the intermediates, are defined nicely by their disproportionately enlarged heads. Moreover, there is an accentuation of feminine traits in the thorax of the intermediates and especially of the majors, the sclerites being well delimited and bearing a striking resemblance to those of the female caste.

The species which is most likely to be confused with badius in the worker caste is Pogonomyrmex comanche. The configuration of the petiole and post petiole is quite similar in the two, and both species have the nodes rather coarsely and generally transversely rugose. But whereas the dorsum of the petiolar node of comanche, seen in lateral view, is flattened and usually bears a distinct median depression, that of badius is convex and not depressed. Both species have a strongly arched thorax; but comanche possesses perfectly normal epinotal spines whereas badius has an unarmed epinotum under normal conditions, though it may occasionally have aberrant epinotal spination (vide infra). In comanche only the basal face of the epinotum is rugose, the declivous face being free of sculpture; in badius both faces of the epinotum are rugose.

The female of badius should be clearly recognizable. The head is very wide in proportion to its length (CI l18-121) and bears a sharply emarginate midoccipital border; the eyes are small, weakly protuberant, and set low on the sides of the head; the cephalic rugae diverge strongly into the occipital corners; the ultimate basal mandibular tooth is offset in two planes (posteriorly and dorsally, with the mandible in closed resting position); the epinotum is normally unarmed and its basal face is broadly concave. In the male, the scape is unusually long; the mandible is very broad, triangular, strongly convex, and bears 6 or 7 teeth on an oblique masticatory margin; the dorsum of the petiolar node, in lateral view, is distinctly truncate; the shape of the paramere is distinctive. (Cole 1968)

Keys including this Species

Distribution

United States – Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 39.745° to 24.66666667°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

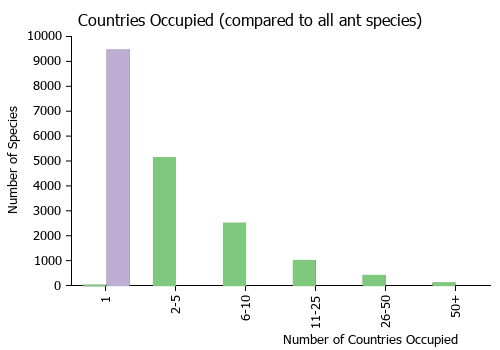

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Biology

Cole (1968) - Pogonomyrmex badius is the only known eastern species in North America. It is confined to the region east of the Mississippi River and is apparently restricted to Coastal Plain states from Louisiana to North Carolina. An old record from New Jersey must be considered as highly doubtful. Although the pine barrens of the New Jersey Coastal Plain have been combed repeatedly by several myrmecologists (Creighton, 1950, p. 116), no subsequent records have come from that state. Moreover, there have been no collections of badius between New Jersey and North Carolina, a region certainly as compatible as New Jersey for establishment of that species. The westernmost records, of which I am aware, are from Lucky, Tangipahoa Parish, and Amite, St. Tamanny Parish, Louisiana. Louisiana is a state of Pogonomyrmex range fringes. Not only does it mark the known western limits of badius, but it also bears the easternmost records of Pogonomyrmex barbatus and Pogonomyrmex comanche. P. badius is unique in that it does not compete with other species of Pogonomyrmex, its range being such that apparently it is never sympatric. Even in Louisiana, barbatus and comanche are far removed geographically from badius. (Cole 1968).

Pogonomyrmex badius nests in sand or sandy soil chiefly of open woodlands and grassy fields and constructs single or multiple, flattened, circular sand craters or dome-shaped sand mounds with depressed tops. Generally the superstructure is free of peripheral vegetation and is littered at least marginally with detritus. I have taken winged forms [rom nests in southern Mississippi in May and June. Van Pelt (1953. p. 166) observed a mating flight in Florida in June. For ethological details of badius the reader is referred to papers by Carter (1962. p. 172), Galley and Gentry (1964), Van Pelt (1953; 1958, pp, 11-12), and Wray (1938).

Nesting Habits

Walter Tschinkel has been studying the nesting biology of this ant for more than a decade.

Nest movement and relocation, Tschinkel 2014. Abstract: The Florida harvester ant (Pogonomyrmex badius) excavates deep nests in the sandy soils of the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains. Nest relocations of over 400 colonies in a north Florida coastal plains pine forest were tracked and mapped from 2010 to 2013. Individual colonies varied from one move in two years to four times a year, averaging about one per year. Almost all moves occurred between May and November peaking in July when more than 1% of the colonies moved per day. Move directions were random, and averaged 4 m, with few moves exceeding 10 m. Distance moved was not related to colony size. Over multiple moves, paths were random walks around the original nest location. Relocation is probably intrinsic to the life history of this species, and the causes of relocation remain obscure— the architecture of old and new nests was very similar, and neither the forest canopy nor the density or size of neighbors was correlated with relocation. Monitoring entire relocations (n = 20) showed that they were usually completed in 4 to 6 days. Moves were diurnal, peaking in the mornings and afternoons dipping during mid-day, and ceasing before sundown. Workers excavated the new nest continuously during the daytime throughout the move and beyond. A minority of workers carried seeds, charcoal and brood, with seeds being by far the most common burden. The proportion of burdened workers increased throughout the move. Measured from year to year, small colonies gained size and large ones lost it. Colonies moving more than once in two years lost more size than those moving less often, suggesting that moving may bear a fitness cost. Colony relocation is a dramatic and consistent feature of the life history of the Florida harvester ant, inviting inquiry into its proximal and ultimate causes.

Soil movement and movement of seeds within nests, Tschinkel et al. 2015. Abstract: During their approximately annual nest relocations, Florida harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex badius) excavate large and architecturally-distinct subterranean nests. Aspects of this process were studied by planting a harvester ant colony in the field in a soil column composed of layers of 12 different colors of sand. Quantifying the colors of excavated sand dumped on the surface by the ants revealed the progress of nest deepening to 2 m and enlargement to 8 L in volume. Most of the excavation was completed within about 2 weeks, but the nest was doubled in volume after a winter lull. After 7 months, we excavated the nest and mapped its structure, revealing colored sand deposited in non-host colored layers, especially in the upper 30 to 40 cm of the nest. In all, about 2.5% of the excavated sediment was deposited below ground, a fact of importance to sediment dating by optically-stimulated luminescence (OSL). Upward transport of excavated sand is carried out in stages, probably by different groups of ants, through deposition, re-transport, incorporation into the nest walls and floors and remobilization from these. This results in considerable mixing of sand from different depths, as indicated in the multiple sand colors even within single sand pellets brought to the surface. Just as sand is transported upward by stages, incoming seeds are transported downward to seed chambers. Foragers collect seeds and deposit them only in the topmost nest chambers from which a separate group of workers rapidly transports them downward in increments detectable as a "wave" of seeds that eventually ends in the seed chambers, 20 to 80 cm below the surface. The upward and downward transport is an example of task-partitioning in a series-parallel organization of work carried out by a highly redundant work force in which each worker usually completes only part of a multi-step process.

Pogonomyrmex badius is known to remove seeds (Atchison & Lucky, 2022; Stamp & Lucus, 1990).

Flight Period

| X | X | X | |||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Hymenoptera

This species is a host for the eucharitid wasp Kapala floridana (a parasite) (Universal Chalcidoidea Database) (primary host).

Fungi

This species is a host for the fungus Myrmicinosporidium durum (a pathogen) in United States (Pereira, 2004; Espadaler & Santamaria, 2012).

Life History Traits

- Mean colony size: 4,300 (Brian et al., 1967; Holldobler & Wilson, 1970; Beckers et al., 1989)

- Foraging behaviour: mass recruiter (Brian et al., 1967; Holldobler & Wilson, 1970; Beckers et al., 1989)

Castes

One of the most interesting aspects of badius is the pronounced degree of polymorphism in the worker caste. This species is the only member of its genus in North America that is polymorphic. The major workers have enormous heads provided with powerful blunt-toothed or edentate (eroded) mandibles which must be very effective in cracking seeds. The minors are "normal." Connecting these two subcastes are intermediates of variable size. (Cole 1968)

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103057. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

| |

| Worker (major/soldier). Specimen code casent0104423. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0103056. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0104422. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Male

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0104421. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by ABS, Lake Placid, FL, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- badius. Formica badia Latreille, 1802c: 238, pl. 11, fig. 71 (w.q.) U.S.A. Lepeletier, 1835: 175 (m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1960b: 2 (l.); Taber, Cokendolpher & Francke, 1988: 51 (k.). Combination in Aphaenogaster: Roger, 1863b: 30; in Pogonomyrmex: Mayr, 1870b: 971. Senior synonym of transversa (and its junior synonyms brevipennis, crudelis): Emery, 1895c: 310. See also: Cole, 1968: 148; Gordon, 1984: 413; Hölldobler & Wilson, 1971: 385; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1356.

- crudelis. Atta crudelis Smith, F. 1858b: 170 (w.q.) U.S.A. Mayr, 1862: 741 (m.). Combination in Myrmica: Mayr, 1862: 740; in Pogonomyrmex: Mayr, 1868b: 170. Junior synonym of transversa: Mayr, 1886c: 359.

- brevipennis. Myrmica brevipennis Smith, F. 1858b: 130 (m.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of transversa: Mayr, 1886c: 359.

- transversa. Myrmica transversa Smith, F. 1858b: 129 (w.) U.S.A. Combination in Pogonomyrmex: Mayr, 1886c: 359. Senior synonym of brevipennis, crudelis: Mayr, 1886d: 450. Junior synonym of badius: Emery, 1895c: 310.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Cole (1968) - HL 1.60-2.05 mm, HW 1.52-2.01 mm, CI 95.0-98.0, SL 1.33-1.56 mm, SI 77.6-87.0, EL 0.27-0.42 mm, EW 0.23-0.30 mm, OI 16.9-20.5, WL 1.90-2.20 mm, PNL 0.49-0.57 mm, PNW 0.38-0.46 mm, PPL 0.49-0.61 mm, PPW 0.53-0.68 mm.

Conformation of mandible as shown in Pl. III, Fig. 19; the 7 teeth rather long, well separated, well developed, subacute; subapical tooth distinctly shorter than apical, its length subequal to first basal; length of second and third basals and ultimate basal subequal; ultimate basal only a little longer than penultimate basal, not offset from the straight or slightly concave basal mandibular margin.

Base of antennal scape as illustrated in Pl. I, Fig. 7; curvature of shaft strong, confined largely to basal one-half of shaft, not notably constricted, not flattened. Basal enlargement only moderately strong; superior lobe much reduced; superior declivity straight, meeting shaft evenly at nearly a su-aight angle; inferior lobe prominent, elongate, subacute; inferior declivity nearly straight, meeting shaft smoothly at a very weak and broadly rounded angle; basal flange prominent, extending well outward from its base, curved strongly distad of the base and roofing a large concavity but not curved inward, extending well outward from apex of superior lobe; lip strong, very wide, bipartite; longitudinal peripheral carina and point absent; basal enlargement not depressed laterally.

Contour of head, in lateral view, as shown in Pl. II, Fig. 3. With head in full-face view, occipital border nearly straight, the distance across it markedly less than that across median or anterior cephalic region; occipital corners evenly and rather broadly rounded; eyes small, strongly protuberant, placed rather low on sides of head, the distance between their anterior margin and the mandibular insertions distinctly less than that between their posterior margin and the occipital border; frontal lobes strongly elevated, convex mesad, not obscuring bases of antennal scapes; cephalic rugae rather fine, unevenly spaced, diverging from frontal lobes into occipital corners, not forming whorls around the eyes, coarser and concentric on outer margin of antennal fossae; interrugal spaces very densely and rather strongly punctate.

Conformation, in lateral view, of thorax, petiole, and postpetiole as shown in Pl. V, Fig. 8; thorax rather strongly convex; anterior declivity of pronotum long and low, meeting the pronotal collar at a weak, broadly rounded angle; mesoepinotal suture distinctly and broadly impressed; base of epinotum meeting the short, rather steep epinotal declivity at a prominent sharp or narrowly rounded angle; epinotum normally without armature, anomalous spines rarely present. Thoracic rugae coarser, less dense, and somewhat more widely spaced than cephalic rugae; transverse except on mesonotum where they are longitudinal; coarser and more widely spaced on both basal and declivous faces of epinotum. Petiolar node long, rather low, the dorsum broadly and weakly convex, the apex subacute, the posterior declivity very weak, the anterior declivity meeting the peduncle at a pronounced obtuse angle; ventral peduncular process moderately strong and blunt to absent. Entire extreme dorsum of petiolar peduncle with dense, rather long, suberect pubescence; venter of peduncle without hairs. Ventral process of postpetiole moderately strong. Petiole and postpetiole, in dorsal view, as shown in Pl. VII, Fig. 24. Dorsum and sides of posterior portion of petiolar node with prominent, widely spaced rugae which are usually transverse and subparallel. Dorsum of postpetiolar node with fine, closely set, wavy, transverse striae confmed to posterior portion. Thorax, petiole, and postpetiole densely and finely punctate. Entire body except gaster subopaque; gaster shining, densely and finely shagreened. Head, thorax, petiole, and postpetiole medium to dark ferrugineous red; gaster often somewhat paler.

Worker (median and major).

Similar to the minor worker, but with the following notable differences: larger in stature, with the head disproportionately enlarged and in the major strongly emarginate along midoccipital border and hence distinctly chordate in full-face view; mandibular teeth in the major generally strongly eroded, often absent; eyes notably less convex than in the minor; head considerably broader than long, especially in the major; thorax with accentuated female characters, the sutures and sclerites well defined; epinotum unarmed or with one or more, sometimes unilateral, anomalous angles, dentides, or distinct spines; petiolar node of major notably broader than long, with a pronounced nipple; petiolar and postpetiolar nodes covered with rather coarse, dense, mostly transverse, often wavy rugae.

Queen

Cole (1968) - HL 2.66-2.71 mm, HW 3.15-3.31 mm, CI 118.4-120.9, SL 1.86-1.90 mm, SI 57.1-59.0, EL 0.53-0.61 mm, EW 0.30-0.34 mm, OI 11.3-12.1, WL 3.57-3.70 mm, PNL 0.53-0.61 mm, PNW 0.72-0.76 mm, PPL 0.68-0.72 mm, PPW 1.10-1.14 mm.

Mandible similar to that of minor worker, but ultimate basal tooth moderately to rather strongly offset in two planes from basal mandibular margin. Conformation of base of antennal scape as in the worker. Head notably broader than long, the occipital border distinctly and rather sharply emarginate medially; in full-face view, occipital corners very broadly and evenly rounded; head, in profile, with occipital corner very strongly and evenly convex, the curvature into the ventral cephalic margin continuing evenly without flattening and not rneeting the ventral margin at a definite angle. Eyes small, set low on sides of head; with head in full-face view, eyes only slightly break the outline of sides of head. Cephalic rugae rather fine, dense, unevenly spaced; median cephalic fugae strongly divergent into occipital corners; interrugal spaces densely and very finely punctate.

Scutum, in lateral view, broadly convex, not overhanging pronotum anteriorly. Base of epinotum broadly concave, meeting the declivity at a sharp or broadly rounded angle. Epinotum normally unarmed, occasionally with one or more anomalous angles, denticles, or spines. Thorax rather uniformly covered with fine, dense, closely spaced, mostly longitudinal rugae which are coarser and less regular on epinolllm; interrugal spaces mostly without punctures. Petiolar node much broadcr than long; petiolar peduncle with a weak to modcrately strong ventral process, hairs absent. Sculpture of petiole and postpetiole similar to that of the worker.

Head, thorax, petiole, and postpetiole subopaque, deep ferrugineous red; gaster paler, shining, finely and densely shagreened.

Male

Cole (1968) - HL 1.48-1.90 mm, HW 1.63-2.05 mill, CI 107.9- 110.1, SL 0.91-1.06 mm, SI 51.7-52.8, EL 0.49-0.57 mm, EW 0.27-0.31 mm, OI 30.1-33.1, WL 2.58-3.50 mm, PNL 0.53-0.61 mm, PNW 0.45-0.65 mm, PPL 0.61-0.76 mm, PPW 0.76-1.10 mm.

Contour of head, in full-face view, as shown in Pl. II, Fig. 10. Conformation of mandible as illustrated in PI. VIII, Fig. 16; blade very broad, subtriangular, the apical margin weakly convex distally and concave basally; masticatory margin strongly oblique; distal portion of blade very markedly and evenly curved inward. With 5 to 7 teeth; apical tooth strong, moderately broad basally; subapical tooth much shorter than apical, the two closely spaced; basal teeth well developed, subequal. In respose, mandibles overlap transversely for nearly one-half their length, the masticatory margin of one mandible completely obscured by covering mandible (Pl. VIII, Fig. 23). Antennal scape rather long, extending in repose about one-third its length beyond posterior border of eye. With head in full-face view, the dorsum subtriangular, the apex rather sharp. Head covered with fine, dense, closely spaced rugae; interrugal spaces finely and faintly punctate.

Base of epinotum meeting declivity at a weak, broadly rounded angle; epinotum generally unarmed, sometimes bearing one or more, frequently unilateral, anomalous spines. Apex of petiolar node, in lateral view, broad and truncate, the posterior declivity pronounced. Petiolar peduncle without a ventral process; ventral hairs absent. Petiolar node with rather sparse, transverse or longitudinal rugulae or striae; interrugal spaces minutely punctate. Ventral process of post petiole very weak. Paramere of genitalia as shown in Pl. X. Fig. 15 and P. XI. Fig. 16; volsella. in full ventral view, as in PI. XI, Fig. 21.

Head and thorax subopaque; petiole and postpetiole somewhat shining; gaster strongly shining, not shagreened. Head, thorax, petiole. and postpetiole deep brownish black; gaster pale yellowish brown.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- 2n = 32 (USA) (Taber et al., 1988).

References

- Atchison, R. A., Lucky, A. 2022. Diversity and resilience of seed-removing ant species in Longleaf Sandhill to frequent fire. Diversity 14, 1012 (doi:10.3390/d14121012).

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Baraibar, B., Ledesma, R., Royo-Esnal, A., Westerman, P.R. 2011. Assessing yield losses caused by the harvester ant Messor barbarus (L.) in winter cereals. Crop Protection 30(9), 1144–1148 (doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2011.05.010).

- Barbero, F., Bonelli, S., Thomas, J.A., Balletto, E., Schonrogge, K. 2009. Acoustical mimicry in a predatory social parasite of ants. Journal of Experimental Biology 212, 4084–4090. (doi:10.1242/JEB.032912).

- Barbero, F., Patricelli, D., Witek, M., Balletto, E., Casacci, L.P., Sala, M., Bonelli, S. 2012. Myrmica Ants and Their Butterfly Parasites with Special Focus on the Acoustic Communication. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2012, 1–11 (doi:10.1155/2012/725237).

- Beckers R., Goss, S., Deneubourg, J.L., Pasteels, J.M. 1989. Colony size, communication and ant foraging Strategy. Psyche 96: 239-256 (doi:10.1155/1989/94279).

- Bhattacharyya, K., Annagiri, S. 2019. Characterization of nest architecture of an Indian ant Diacamma indicum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science 19, 9 (doi:10.1093/jisesa/iez083).

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Chernyshova, A.M. 2021. A genetic perspective on social insect castes: A synthetic review and empirical study. M.S. thesis, The University of Western Ontario. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7771.

- Cole, A. C., Jr. 1968. Pogonomyrmex harvester ants. A study of the genus in North America. Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, x + 222 pp. (page 148, see also)

- Cushing, P.E. 2012. Spider-ant associations: An updated review of myrmecomorphy, myrmecophily, and myrmecophagy in spiders. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2012, 1–23 (doi:10.1155/2012/151989).

- Davis, T. 2009. The ants of South Carolina (thesis, Clemson University).

- Deyrup, M.A., Carlin, N., Trager, J., Umphrey, G. 1988. A review of the ants of the Florida Keys. Florida Entomologist 71: 163-176.

- Emery, C. 1895d. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Geogr. Biol. Tiere 8: 257-360 (page 310, Senior synonym of transversa (and its junior synonyms brevipennis and crudelis))

- Espadaler, X., Santamaria, S. 2012. Ecto- and Endoparasitic Fungi on Ants from the Holarctic Region. Psyche Article ID 168478, 10 pages (doi:10.1155/2012/168478).

- Gordon, D. M. 1984. Species-specific patterns in the social activities of harvester ant colonies (Pogonomyrmex). Insectes Soc. 31: 74-86 (page 413, see also)

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E. O. 1971 ("1970"). Recruitment trails in the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex badius. Psyche (Cambridge) 77:385-399. [1971-10-21]

- Ipser, R.M., Brinkman, M.A., Gardner, W.A., Peeler, H.B. 2004. A survey of ground-dwelling ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Georgia. Florida Entomologist 87: 253-260.

- Jansen, G., Savolainen, R. 2010. Molecular phylogeny of the ant tribe Myrmicini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160(3), 482–495 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00604.x).

- Latreille, P.A. 1802. Histoire naturelle des fourmis, et recueil de mémoires et d'observations sur les abeilles, les araignées, les faucheurs, et autres insectes. Paris: Impr. Crapelet (chez T. Barrois), xvi + 445 pp.

- Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, A. 1835 [1836]. Histoire naturelle des insectes. Hyménoptères. Tome I. Paris: Roret, 547 pp. (page 175, male described)

- MacGown, J.A., Booher, D., Richter, H., Wetterer, J.K., Hill, J.G. 2021. An updated list of ants of Alabama (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with new state records. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 147: 961-981 (doi:10.3157/061.147.0409).

- Mayr, G. 1870b. Neue Formiciden. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 20: 939-996 (page 971, Combination in Pogonomyrmex)

- Meurville, M.-P., LeBoeuf, A.C. 2021. Trophallaxis: the functions and evolution of social fluid exchange in ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 31: 1-30 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:001).

- Módra, G., Maák, I., Lőrincz, Á., Lőrinczi, G. 2021. Comparison of foraging tool use in two species of myrmicine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux (doi:10.1007/s00040-021-00838-0).

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Paul, J. Gronenberg, W. 1999. Optimizing force and velocity: mandible muscle fibre attachments in ants. Journal of Experimental Biology 202, 797-808.

- Pereira, R.M. 2004. Occurrence of Myrmicinosporidium durum in red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, and other new host ants in eastern United States. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 86: 38-44 (doi:10.1016/j.jip.2004.03.005).

- Roger, J. 1863b. Verzeichniss der Formiciden-Gattungen und Arten. Berl. Entomol. Z. 7(B Beilage: 1-65 (page 30, Combination in Aphaenogaster)

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Pr (page 1356, see also)

- Stamp, N.E., Lucas, J.R. 1990. Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation. Journal of Ecology 78, 589–600.

- Taber, S. W.; Cokendolpher, J. C.; Francke, O. F. 1988. Karyological study of North American Pogonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Soc. 35: 47-60 (page 51, karyotype described)

- Tschinkel, W. R., W. J. Rink, and C. L. Kwapich. 2015. Sequential Subterranean Transport of Excavated Sand and Foraged Seeds in Nests of the Harvester Ant, Pogonomyrmex badius. Plos One. 10.0139922 24pp. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139922

- Tschinkel, W.R. 1999. Sociometry and sociogenesis of colonies of the harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex badius: Distribution of workers, brood and seeds within the nest in relation to colony size and season. Ecological Entomology 24: 222-237.

- Tschinkel, W.R. 2004b. The nest architecture of the Florida harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex badius. Journal of Insect Science 4: 21.

- Tschinkel, W.R. 2014. Nest Relocation and Excavation in the Florida Harvester Ant, Pogonomyrmex badius. PLoS ONE. 9:e112981. 18pp. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112981

- Tschinkel, W.R. 2015. The architecture of subterranean ant nests: beauty and mystery underfoot. Journal of Bioeconomics 17:271–291 (DOI 10.1007/s10818-015-9203-6).

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1960b. Supplementary studies on the larvae of the Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 62: 1-32 (page 2, larva described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Annotated Ant Species List Ordway-Swisher Biological Station. Downloaded at http://ordway-swisher.ufl.edu/species/os-hymenoptera.htm on 5th Oct 2010.

- Behrmann N. B. E., F. A. Milesi, J. Lopez de Casenave, R. G. Pol, and B. Pavan. 2010. Colony size and composition in three Pogonomyrmex ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the central Monte desert, Argentina. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 69 (1-2): 117-122.

- Braman C. A., and B. T. Forschler. 2018. Survey of Formicidae attracted to protein baits on Georgia’s Barrier Island dunes. Southeastern Naturalist 17(4): 645-653.

- Dash S. T. and L. M. Hooper-Bui. 2008. Species diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Louisiana. Conservation Biology and Biodiversity. 101: 1056-1066

- Deyrup M., C. Johnson, G. C. Wheeler, J. Wheeler. 1989. A preliminary list of the ants of Florida. Florida Entomologist 72: 91-101

- Deyrup, M. and J. Trager. 1986. Ants of the Archbold Biological Station, Highlands County, Florida (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Florida Entomologist 69(1):206-228

- Deyrup, Mark A., Carlin, Norman, Trager, James and Umphrey, Gary. 1988. A Review of the Ants of the Florida Keys. The Florida Entomologist. 71(2):163-176.

- Feener D.H.,Jr. 1987. Response of Pheidole morrisi to two species of enemy ants, and a general model of defense behavior in Pheidole. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 60: 569-575.

- Forster J.A. 2005. The Ants (hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama. Master of Science, Auburn University. 242 pages.

- General D.M. & Thompson L.C. 2007. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Arkansas Post National Memorial. Journal of the Arkansas Acaedemy of Science. 61: 59-64

- Graham J.H., H.H. Hughie, S. Jones, K. Wrinn, A.J. Krzysik, J.J. Duda, D.C. Freeman, J.M. Emlen, J.C. Zak, D.A. Kovacic, C. Chamberlin-Graham, H. Balbach. 2004. Habitat disturbance and the diversity and abundance of ants (Formicidae) in the Southeastern Fall-Line Sandhills. 15pp. Journal of Insect Science. 4: 30

- Graham, J.H., A.J. Krzysik, D.A. Kovacic, J.J. Duda, D.C. Freeman, J.M. Emlen, J.C. Zak, W.R. Long, M.P. Wallace, C. Chamberlin-Graham, J.P. Nutter and H.E. Balbach. 2008. Ant Community Composition across a Gradient of Disturbed Military Landscapes at Fort Benning, Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 7(3):429-448

- Ipser R. M. 2004. Native and exotic ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Georgia: Ecological Relationships with implications for development of biologically-based management strategies. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Georgia. 165 pages.

- Ivanov K., L. Hightower, S. T. Dash, and J. B. Keiper. 2019. 150 years in the making: first comprehensive list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Virginia, USA. Zootaxa 4554 (2): 532–560.

- Johnson C. 1986. A north Florida ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insecta Mundi 1: 243-246

- Johnson R. A., and C. S. Moreau. 2016. A new ant genus from southern Argentina and southern Chile, Patagonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 4139: 1-31.

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Klotz, J.H., J.R. Mangold, K.M. Vail, L.R. Davis Jr., R.S. Patterson. 1995. A survey of the urban pest ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Peninsular Florida. Florida Entomologist 78(1):109-118

- Lubertazzi D. and Tschinkel WR. 2003. Ant community change across a ground vegetation gradient in north Floridas longleaf pine flatwoods. 17pp. Journal of Insect Science. 3:21

- MacGown J. A. 2015. Report on the ants collected on Spring Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina. A report submitted to Spring Island Nature Preserve, May 2015. Mississippi Entomological Museum Report #2015-01. 8 pp

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, L. C. Majure, and J. L. Seltzer. 2008. Rediscovery of Pogonomyrmex badius(Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Mainland Mississippi, with an Analysis of Associated Seeds and Vegetation. Midsouth Entomologist 1: 17-28.

- MacGown J. A., J. G. Hill, and M. Deyrup. 2009. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Little Ohoopee River Dunes, Emanuel County, Georgia. J. Entomol. Sci. 44(3): 193-197.

- MacGown J. A., and R. Whitehouse. 2015. A preliminary report of the ants of West Ship Island. A report submitted to the Gulf Islands National Seashore. Mississippi Entomological Museum Report #2015-02. 9 pp.

- MacGown, J.A and J.A. Forster. 2005. A preliminary list of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Alabama, U.S.A. Entomological News 116(2):61-74

- MacGown, J.A. and T. Lockley. Ants of Horn Island, Jackson County, Mississippi

- Moreau C. S., M. A. Deyrup, and L. R. David Jr. 2014. Ants of the Florida Keys: Species Accounts, Biogeography, and Conservation (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Insect Sci. 14(295): DOI: 10.1093/jisesa/ieu157

- Olsen O. W. 1934. Notes on the North American harvesting ants of the genus Pogonomyrmex Mayr. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 77: 493-514.

- Rheindt, F.E., J. Gadau, C.-P. Strehl and B. Holldobler. 2004. Extremely High Mating Frequency in the Florida Harvester Ant (Pogonomyrmex badius). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 56(5):472-481

- Rheindt, F.E., S.P. Strehl and J. Gadau. 2005. A genetic component in the determination of worker polymorphism in the Florida harvester ant Pogonomyrmex badius. Insectes Sociaux 52:163-168

- Smith M. R. 1934. Dates on which the immature or mature sexual phases of ants have been observed (Hymen.: Formicoidea) (continued from page 251). Entomological News 45: 264-267.

- Smith, C.R., C. Schoenick, K.E. Anderson, J. Gadau and A.V. Suarez. 2007. Potential and realized reproduction by different worker castes in queen-less and queen-right colonies of Pogonomyrmex badius. Insectes Sociaux 54:260-267

- Strehl, C.-P. and J. Gadau. 2004. Cladistic Analysis of Paleo-Island Populations of the Florida Harvester Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Based upon Divergence of Mitochondrial DNA Sequences. The Florida Entomologist 87(4):576-581

- Taber S. W., J. C. Cokendolpher, and O. F. Francke. 1988. Karyological study of North American Pogonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Soc. 35: 47-60.

- Trager, J. and C.Johnson. 1985. A slave-making ant in Florida: Polyergus lucidus with observations on the natural history of its host Formica archboldi (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). The Florida Entomologist 68(2):261-266.

- Van Pelt A. F. 1948. A Preliminary Key to the Worker Ants of Alachua County, Florida. The Florida Entomologist 30(4): 57-67

- Van Pelt A. F. 1966. Activity and density of old-field ants of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 82: 35-43.

- Van Pelt A., and J. B. Gentry. 1985. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the Savannah River Plant, South Carolina. Dept. Energy, Savannah River Ecology Lab., Aiken, SC., Report SRO-NERP-14, 56 p.

- Warren, L.O. and E.P. Rouse. 1969. The Ants of Arkansas. Bulletin of the Agricultural Experiment Station 742:1-67

- Wheeler W. M. 1904. The ants of North Carolina. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 20: 299-306.

- Wheeler W. M. 1913. Ants collected in Georgia by Dr. J. C. Bradley and Mr. W. T. Davis. Psyche (Cambridge) 20: 112-117.

- Wheeler W. M. 1932. A list of the ants of Florida with descriptions of new forms. J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 40: 1-17.

- Whitcomb W. H., H. A. Denmark, A. P. Bhatkar, and G. L. Greene. 1972. Preliminary studies on the ants of Florida soybean fields. Florida Entomologist 55: 129-142.

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- Photo Gallery

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Nesting Notes

- FlightMonth

- Eucharitid wasp Associate

- Host of Kapala floridana

- Fungus Associate

- Host of Myrmicinosporidium durum

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Pogonomyrmecini

- Pogonomyrmex

- Pogonomyrmex badius

- Myrmicinae species

- Pogonomyrmecini species

- Pogonomyrmex species

- Ssr