Pheidole militicida

| Pheidole militicida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Pheidole |

| Species: | P. militicida |

| Binomial name | |

| Pheidole militicida Wheeler, W.M., 1915 | |

P. militicida builds crater nests, often surrounded by piles of seed chaff in the soil of deserts. Stefan Cover and Gary D. Alpert (unpublished collection data) found nests at 1300–1500 m; winged queens and males are present in at least the first half of July, in separate collections by G. D. Alpert, W. S. Creighton, and S. P. Cover. The species is also a major seed harvester in xeric habitats. Hölldobler and Möglich (1980) have described trunk trails laid out by minors along which thousands of ants travel to the areas where seeds are then harvested and brought back to the nest. The system resembles that of the famous desert harvester ants of the genera Messor and Pogonomyrmex. The trunk trails start as chemical recruitment trails and are stabilized by more enduring chemical orientation cues and visual markers. And like Messor, the workers shift the direction of the foraging pathway or establish a new route when the seed supplies in the target foraging area diminish. Because W. M. Mann and W. M. Wheeler found majors in the nests near Benson, Arizona, in the seed-bearing season of August and remains of majors on the chaff piles in November, Wheeler (1915b) speculated that majors are produced in the colony prior to the harvesting season and killed afterward—hence the name he gave the species. (Wilson 2003)

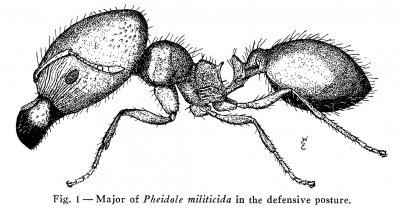

Identification

Mackay and Mackay (2002) - The majors of this species are large (head length, excluding mandibles, > 2 mm, total length of ant more than 5 mm). The anterior 1/3 of the head is sculptured with rugae, the intrarugal spaces are mostly shining, and the posterior 2/3 of the length of the head is smooth and glossy. The dorsum of the pronotum is smooth and glossy, the promesonotum forms a single, convex unit, and the dorsum of the propodeum is nearly flat. The propodeal spines are well developed, but are thick and blunt. The apex of the petiole is sharp in profile, concave as seen from behind; the postpetiole is wide with well-developed connules, as seen from above.

The structure of the promesonotum is similar to that of Pheidole clydei, but the 3-segmented club and the predominantly glossy and shiny head easily separates this species from the latter mentioned species.

The minor workers are remarkably small, most slightly longer than 2 mm, the head is smooth and glossy, the pronotum is smooth and glossy, and the remainder of the mesosoma is sculptured but at least moderately smooth and glossy. The smooth and glossy pronotum, as well as the moderately glossy remainder of the mesosoma, separates the minor workers of this species from many of the others, but it may be difficult to recognize his species on the basis of the minor workers only.

Also see the description in the nomenclature section.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Southern Arizona, New Mexico, extreme western Texas. (Wilson 2003)

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 34.156971° to 31.323322°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

Creighton and Creighton (1959) disproved Wheeler's theory that the majors were killed after the late summer seed production season ended. Majors were found to fill the role of nest defense but did not appear to be needed for seed milling. They found that majors were difficult to find when digging up nests, likely explaining the paucity of this caste mentioned in earlier studies. "Our original attempts to secure majors were based upon the obvious method of digging out the colony. This proved to be the worst possible way to get them. Under ordinary conditions only two or three majors stay in the passages near the nest entrance. Since the major of militicida is extraordinarily clumsy, it is seldom able to extricate, itself if covered with soil. Hence, it is extremely likely to be missed when the nest is dug out, for the major will often remain perfectly quiet if only a thin layer of soil covers it. To be sure that the majors have not been missed, the soil must be sifted as the nest is excavated."

Additional observations from Creighton and Creighton (1959) are provided in what follows. This account of the biology of Pheidole militicida is important in providing detailed information regarding Pheidole foraging behavior, seed use and the defensive behavior or majors.

Baiting seldom failed to produce majors in quantity if continued long enough. One colony which was baited for five successive days in February yielded a total of seventy-seven majors. Moreover, by using bait majors were secured from nests which had produced none when dug out. For, with one exception, the excavated nests reestablished themselves after a few weeks. This is clear evidence that these nests had not been fully exposed. The character of the militicida nest would make complete exposure difficult. All the nests that we have encountered have been built in light, riable soil between large stones. As these stones are removed the soil between them crumbles away and this obliterates any passages that were in it. As a result it is usually impossible to follow the passages to any depth and as excavation proceeds there is not the slightest indication of the direction it should take.

In areas where Pheidole militicida is abundant there are often places where several nest entrances are close together. The distance between the entrances will vary from two to eight feet. It seems impossible at present to state whether each entrance represents, a separate nest or whether they all belong to a single elongated nest. It was soon found that majors and minors from entrances a few feet apart could be mixed together without showing any signs of animosity. The same result could be secured with specimens from nests a half a mile or more apart. The only explanation that would seem to fit this surprising behavior is that militicida is almost totally devoid of inter-colony animosity.

The sexual brood is brought to maturity at this time with the marriage flight following in early July.

We expected P. militicidato forage sporadically during the winter but it was a surprise to discover that it is one of the most consistent winter foragers in the area where it occurs. The only other ant which shows comparable activity is Myrmecocystus mimicus. Except for one or two days when rain or snow ell, the minors of militicida were out every day during January, February and early March. As a rule the foraging did not begin until 3:oo P.M. By that time the surface temperature had reached 60F. (16C.) or better. Full foraging activity developed when the surface temperature reached 90F. (31C.). During January the surface temperature drops rapidly towards sundown and foraging in that month ordinarily terminates soon after 5:00 P.M. This brief period of foraging is extended as the days lengthen and by the end of February the foraging lasts about three hours. During the winter months the seeds of two grasses are the principal ones collected. These are the fluff grass, Tridens pulchellus Hitch and the spike pappus grass, Enneapogon desvauxii Beauv. Both these grasses fail to lose all their seeds at the end of the growing season, but the number of unshed seeds in the heads is low. Counts on five samples (3o cc. each) of fluff grass heads taken within foraging range of five militicida colonies gave an average of only 4.6 seeds per cubic centimeter. Nevertheless, these residual seeds furnish a steady, if meager, supply for, as the winter advances, the seeds or the spikelets containing them are gradually blown out of the heads and deposited in a thin layer on the surface of the soil wherever there is a windbreak. In the winter months the militicida minors collect their seeds entirely from this layer. Despite the short foraging period and the scant seed supply, the militicida minors bring in many seeds, for on warm days foraging is very active. Each nest entrance usually has a single foraging column but sometimes two or three columns may leave the same entrance. The columns are seldom more than fifteen feet long, an indication of the easy availability of the seed supply, regardless of its low yield. Since the rate of seed consumption in the captive colonies was very low, it seems probable that winter foraging augments the number of seeds stored in the nests. There is abundant evidence that when the seeds are stored they are entire.

The minors in our artificial nests spent many hours arranging and rearranging the seeds in groups. We take this to be the equivalent of the packing of the seed chambers in a free, nest. We were surprised to discover that all the seeds opened in the artificial colonies were opened by the minors. The majors never made the slightest efforts to open the seeds and rarely paid any attention to them once their envelopes had been removed. In an effort to force the majors to crack open seeds, several nests containing only majors were set up. These were liberally supplied with seeds of T. pulchellus. Some of the majors in these nests lived for several weeks but they never made any attempt to open the seeds and ultimately all of them died, apparently from starvation, in the midst of the seeds which could have supplied them with food. The minors open the, seeds of pulchellus and desvauxii by gnawing at the pointed end of the seed. Sometimes the seed is held by one minor and gnawed open by another, but a more common method involves only one, minor, who places the blunt end of the seed on the floor of the nest and, with the. seed held in a vertical position gnaws at its pointed end. The seeds of desvauxii are entirely consumed but those of pulchellus are usually only half eaten. This may be due to the fact that in pulchellus the embryo is confined to the half of the seed which the ants eat, whereas in desvauxii the embryo extends more than three quarters the length of the seed.

The major of militicida has a very limited part in the harvesting operations and even this small part can be handled equally well by the minors. It seemed unlikely that the major would be limited to so small a share in the activities of the colony. The first hint that they might perform some unique activity essential to the colony was provided by the majors who came out of the nests during baiting. The junior author, who spent much time at this work, noticed that before the major emerged from the nest it would often stand for a considerable period just inside the nest entrance. When it did so it was a thorough nuisance to the minors, who had difficulty in getting past what amounted to a road block. When the major finally emerged from the nest it usually opened its jaws to their fullest extent and made short lunges in the direction of small pebbles and bits of grass as though it were trying to bite them. Later it was found that this same lunging and biting response could be eliciced by throwing a small beam of light into the opening before the major left it. It was further clear that the primary reason why the major left the nest was not hunger. They almost never went directly to the bait, but wandered around in their clumsy fashion as though they were looking for something else. It was only after considerable patrol that some of them would go to the bait. These responses suggested that the function of the major might be to guard the nest entrance and, to test this, a nest was constructed which gave them the opportunity to do so.

This nest consisted of two chambers connected by a single, long passage which could be blocked or unblocked in the middle without disturbing the nest. The block consisted of a cotton plug which could be pushed into the connecting passage through a glass tube set at right angles to it. With the plug in place the .nest was divided into two separate chambers; with the plug removed the two. chambers communicated with each other through the single connecting passage. After the plug was in place majors and minors of militicida were placed in one chamber and their prospective intruders in the other. The nest was then set aside until both groups were accustomed to their surroundings. Usually it took no more than twelve hours for each group to become thoroughly tranquil and to demonstrate by this tranquility that it was unaware of the other group’s presence nearby.

The ants selected as intruders were Pogonomyrmex maricopa and Pogonomyrmex californicus. This choice was made because both species occur in close proximity to militicida colonies in the field and the harvesting activities of all three species lead to frequent encounters outside the nests. On the removal of the blocking cotton plug both groups would begin to explore the communicating passage. The Pogonomyrmex workers moved slowly into the passage but rapidly backed out of it when they became aware of the advancing militicida workers. In most cases the militicida minors first entered the passage. Some of them would usually be seized and killed by the Pogonomyrmex workers but others returned to the nest and alerted the majors. When these entered the passage they showed precisely the reactions that they had exhibited around their nest entrances. They advanced very cautiously, with the jaws wide open, and made frequent short lunges in the direction of the Pogonomyrmex workers. As the militicida majors wedged themselves tightly into the passage, three or four ranks deep, the passage was completely blocked and the front face of this block was a highly dangerous area for the Pogonomyrmex workers for it consisted of the closely approximated heads and wide open jaws of the militicida majors. As to what happened next depended on the Pogonomyrmex workers, who would charge up to the barrier and slash at the militicida majors with their mandibles. These attacks were usually futile, tor the only exposed parts of the militicida major which could be damaged were the antennae and these were held so closely against the head that the Pogonomyrmex workers were seldom able to grasp them. If these attacks were vigorously pressed the Pheidole militicida major usually stood perfectly still and waited until the mandibles of its opponent were near its own. It then lunged toward, closed its jaws on the mandible of the Pogonomyrmex worker and attempted to break off the crushed mandible. The majors did not always succeed in doing so, particularly in the case of maricopa, whose heavy mandibles are hard to break, but they seldom iailed to. mangle the mandible so badly that it was useless. It may be added that this attack on the mandible is deliberate, for the militicida major will rarely strike at other parts when these are presented. We have repeatedly seen the Pogonomyrmex workers thrust their antennae or legs between the open jaws of the militicida major without causing the major to strike. They do not do so until there is a good chance that the mandible can be grasped and they rarely miss their target. After a number of Pogonomyrmex workers had been put out of action with useless mandibles, or sooner it the Pogonomyrmex workers did not press the attack vigorously, the militicida majors emerged from the passage and began a different sort of action. They no longer faced their opponents and struck at their mandibles but approached them from the rear and struck at the thorax or the petiolar nodes. As a result, most of the Pogonomyrmex workers were ultimately cut in two, either at the petiole or behind the pronotum. In this more open fighting it was also obvious that the petiolar nodes and the mesothoracic area were the principal targets. An examination of the Pogonomyrmex workers at the end of an engagement always showed much damage to mandibles, thorax and petiolar nodes and surprisingly little damage to legs and antennae. In short, there is nothing haphazard about the way in which the militicida majors deal with their opponents; they only strike at parts which will put their opponents out of action or kill them. It is clear that their method is highly effective for it was only occasionally that the Pogonomyrmex workers got the better of the engagement. Even when they outnumbered the militicida majors they often failed to kill a single one of them and when they did so it was usually a result of the militicida major having been stung. This incapacitates them but does not immediately kill them.

The P. militicida major shows an efficiency that is completely unlike its bumbling efforts elsewhere. This, plus the fact that these responses are repeated with surprising exactness time after time, and by majors from different nests, leads us to conclude that they are the normal guarding responses of the militicida major. If this is true the major of militicida is best regarded as a soldier. Its role in the harvesting activities of the colony is slight and it is not primarily a seed-crusher, as has been mistakenly supposed.

Castes

Worker

Minor

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0102885. Photographer April Nobile, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Major

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- militicida. Pheidole militicida Wheeler, W.M. 1915b: 398 (s.w.) U.S.A. Creighton & Gregg, 1955: 11 (q.m.). See also: Wilson, 2003: 586.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

From Wilson (2003): DIAGNOSIS A giant species of the pilifera group distinguished in addition as follows.

Major: reddish yellow; petiolar node in side view tapering to a blunt point, its apex bearing a transverse carina; the postpetiolar node from above angulate, its crest also bearing a transverse carina; a small, angular subpostpetiolar process present; the posterior half of the head and almost all the rest of the body smooth and shiny; pilosity erect, relatively short, and very dense.

Minor: eye very large, head quadrate in full-face view; humerus lobose in dorsal-oblique view; postpetiolar node depressed; almost all of the body smooth and shiny.

MEASUREMENTS (mm) Syntype major: HW 2.66, HL 2.50, SL 0.96, EL 0.32, PW 1.20. Syntype minor: HW 0.84, HL 0.92, SL 0.74, EL 0.26,. PW 0.52.

COLOR Major: concolorous reddish yellow.

Minor: body dark reddish brown, appendages brownish yellow.

Figure. Upper: syntype, major. Lower: syntype, minor. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Type Material

ARIZONA: Hereford, Cochise Co. Museum of Comparative Zoology - as reported in Wilson (2003)

Etymology

L militicida, soldier killer, based on Wheeler’s mistaken belief that colonies of this species periodically execute their own majors. (Wilson 2003)

References

- Wilson, E. O. 2003. Pheidole in the New World: A dominant, hyperdiverse ant genus. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. (page 586, fig. major, minor described)

- Creighton, W. S.; Gregg, R. E. 1955. New and little-known species of Pheidole (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Univ. Colo. Stud. Ser. Biol. 3: 1-46 (page 11, queen, male described)

- Hölldobler, B. and M. Möglich. 1980. The foraging system of Pheidole militicida (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ins. Soc. 27:237–264.

- Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY.

- Wheeler, W. M. 1915b. Some additions to the North American ant-fauna. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 34: 389-421 (page 398, soldier, worker described)

- Creighton, W. S. and M. P. Creighton. 1959. The Habits of Pheidole a Militicida Wheeler (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche. 66:1-12.

- Ruano, F., Tinaut, A., Soler, J.J. 2000. High surface temperatures select for individual foraging in ants. Behavioral Ecology 11, 396-404.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Mackay W. P. and Mackay, E. E. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 400 pp.

- Nash M. S., W. G. Whitford, J. Van Zee, and K. M. Havstad. 2000. Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) responses to environmental stressors in the Northern Chihuahuan Desert. Environ. Entomol, 29(2): 200-206.

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1985. A checklist of Texas ants. Prairie Naturalist 17:49-64.

- Whitford W. G. 1978. Structure and seasonal activity of Chihuahua desert ant communities. Insectes Sociaux 25(1): 79-88.

- Wilson, E.O. 2003. Pheidole in the New World: A Dominant, Hyperdiverse Genus. Harvard University Press