Veromessor andrei

| Veromessor andrei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Stenammini |

| Genus: | Veromessor |

| Species: | V. andrei |

| Binomial name | |

| Veromessor andrei (Mayr, 1886) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Nests of Veromessor andrei occur in open sites in most soil types and consist of one to multiple entrances with irregularly-shaped entrances up to 5 cm in diameter. Nest entrances usually are surrounded by an irregular gravel mound of excavated soil and chaff that ranges up to 60 cm in diameter (Boulton, Jaffee, & Scow, 2003; Creighton, 1953; Snelling & George, 1979; Wheeler & Creighton, 1934). Workers of V. andrei are mostly monomorphic (Wheeler & Creighton, 1934). (Johnson et al., 2022) Workers forage in files and collect seeds which are apparently stored in the nest, to judge from the chaff which surrounds the nest entrance. This chaff is scattered about and not formed into a crescent or ring as in the case of Veromessor pergandei (Wheeler and Creighton 1934).

Identification

Worker

This species is uniquely characterized by the following combination of features (Johnson et al., 2022):

- Usually dark reddish-brown to dark brownish, gaster usually darker; some populations in southern California and Baja California light yellowish-orange to ferruginous orange to rust colored; some populations in the Central Valley of California and Monterey area blackish to black

- Medial lobe of clypeus with 2–3 coarse, lateral longitudinal rugae, medial lobe not thick and protuberant in profile, not elevated above lateral lobes in frontal view

- Mandibles with 8 teeth

- Entire circumference of base of scape with a strongly developed and flattened, flared and trumpet-like flange; maximum basal width of scape slightly greater than maximum preapical width

- MOD less than OMD, OI < 23.5

- Cephalic dorsum with coarse, wavy to irregular, longitudinal rugae that usually have short lateral branches posterior to eyes; medial rugae not diverging to weakly diverging toward posterior corners; cephalic interrugae weakly punctulate, weakly shining

- Psammophore poorly developed; ventral surface of head capsule with both J-shaped hairs and straight or evenly curved hairs, J-shaped hairs not arranged in a distinct row

- In dorsal view, anterior margin of pronotum with one to few irregular transverse rugae, remainder usually with strongly irregular, longitudinal rugae to rugoreticulate; sides of pronotum with wavy to strongly irregular rugae that traverse longitudinally to posterodorsally to rugoreticulate; mesosoma with coarse, strongly irregular longitudinal rugae; mesopleura with mostly longitudinal rugae or rugae angle posterodorsally, rugae (especially on dorsal onehalf) often with lateral branches to rugoreticulate; interrugae on mesosoma weakly punctulate, weakly shining

- Propodeal spines very slender, acuminate, not curved in profile or in dorsal view; length > 3.0× the distance between their bases, infraspinal facet and propodeal declivity weakly coriarious or with weak irregular, transverse rugae, moderately to strongly shining

- Metasternal process large, higher than long, apex very broadly rounded to nearly flat, partly translucent (Figures 2–5, 6B)

Queen

Queen diagnosis. This caste is diagnosed by the following combination of features (Johnson et al., 2022):

- Usually dark reddish-brown to dark brown with gaster usually darker; some populations in southern California and Baja California light yellowish-orange to ferruginous orange to rust colored; some populations in the Central Valley of California and Monterey area blackish to black

- Medial lobe of clypeus with 2–3 coarse, lateral longitudinal rugae, medial lobe not thick and protuberant in profile, not elevated above lateral lobes in frontal view

- Mandibles with 8 teeth

- Entire circumference of base of scape with a strongly developed and flattened, flared and trumpet-like flange; maximum basal width of scape slightly greater than maximum preapical width

- MOD slightly less than to slightly greater than OMD

- Cephalic dorsum with coarse, wavy to irregular, longitudinal rugae; medial rugae not diverging to weakly diverging toward posterior corners; cephalic interrugae weakly to moderately punctulate, weakly shining

- Psammophore poorly developed

- Sides of pronotum with irregular longitudinal rugae that often have short lateral branches; mesoscutum with fine, longitudinal rugae, moderately shining; mesoscutellum with longitudinal, oblique, or transverse rugae; anepisternum with longitudinal rugae, katepisternum with longitudinal rugae except for smooth and shining anteroventral margin; interrugae weakly to moderately coriarious, moderately shining

- Sides of propodeum with longitudinal and oblique rugae; propodeal spines elongate-triangular, length about 1.0× the distance between their bases; infraspinal facet with transverse rugae, propodeal declivity smooth and shining

- Metasternal process large, higher than long, apex very broadly rounded to nearly flat, partly translucent (Figures 7–8)

Male

This caste is diagnosed by the following combination of features (Johnson et al., 2022):

- Dark brown to blackish

- Medial lobe of clypeus moderately convex with several irregular, mostly longitudinal rugae

- Mandibles with 3, rarely 4, small teeth basad of preapical tooth

- In frontal view, anterior ocellus above level of top of eyes

- Mesopleura dull to moderately shining; anepisternum densely punctate, usually with fine longitudinal rugae; katepisternum densely punctate, usually with weak, widely scattered longitudinal or oblique rugae

- Propodeum rugose to rugoreticulate, interrugae densely punctate; propodeal spines cariniform or with acuminate denticles to small teeth

- Metasternal process as long as high, tapering to a subangulate to broadly rounded apex

- Anterior angle of subpetiolar process subacute to acute (Figures 1A, 9)

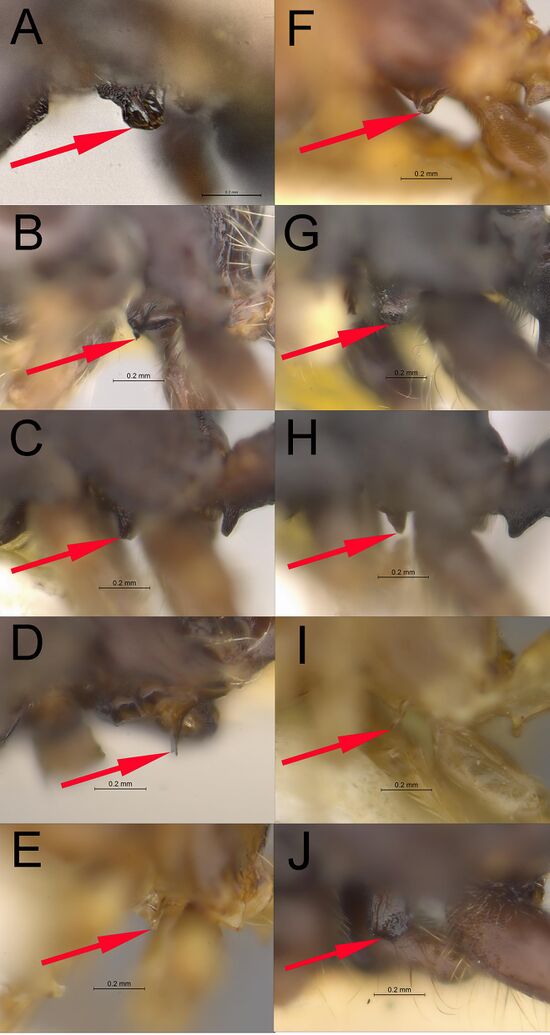

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 1. Photographs of the metasternal process on males of Veromessor: (A) V. andrei (CASENT4010823), (B) V. chamberlini (UCRC_ENT00500152), (C) V. chicoensis (CASENT0869853), (D) V. julianus (LACMENT359792), (E) V. lariversi (CASENT0761204), (F) V. lobognathus (LACMENT363986), (G) V. pergandei (CASENT0869850), (H) V. pseudolariversi (CASENT0869851), (I) V. smithi (LACMENT364071), and (J) V. stoddardi (LACMENT364102). Photographs by Robert Johnson from www.AntWeb.org.

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 1. Photographs of the metasternal process on males of Veromessor: (A) V. andrei (CASENT4010823), (B) V. chamberlini (UCRC_ENT00500152), (C) V. chicoensis (CASENT0869853), (D) V. julianus (LACMENT359792), (E) V. lariversi (CASENT0761204), (F) V. lobognathus (LACMENT363986), (G) V. pergandei (CASENT0869850), (H) V. pseudolariversi (CASENT0869851), (I) V. smithi (LACMENT364071), and (J) V. stoddardi (LACMENT364102). Photographs by Robert Johnson from www.AntWeb.org.

Identification Notes

Veromessor andrei is not likely to be confused with any congener. This species is easily diagnosed by its poorly developed psammophore combined with long propodeal spines (> 3x as long as the distance between their bases), mostly monomorphic workers, and coarse, irregular rugae to rugoreticulate on the cephalic dorsum posterior to eyes and dorsum and sides of pronotum. This species is recognized in the field based on colonies that consist of tens of thousands of workers that forage in columns, usually near dusk and dawn, and it usually occurs in grasslands or similar open habitats (Brown & Gordon, 2000; Creighton, 1953; Wheeler & Creighton, 1934). Veromessor chicoensis and Veromessor stoddardi are the only sympatric species that have a poorly developed psammophore, but both species have short propodeal spines (length less than distance between their bases), strongly polymorphic workers, and cephalic dorsum posterior to eyes and dorsum of pronotum with weak, regular rugae. (Johnson et al., 2022)

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 6. Photographs of the four categories of increasing psammophore development for species of Veromessor based on number and distribution of long J-shaped hairs on the ventral surface of the head capsule (= hypostomal region) (see text). Photograph of: (A) V. chicoensis (CASENT0923125)—J-shaped hairs mostly absent with scattered straight or evenly curved hairs, (B) V. andrei (CASENT0923140)—J-shaped hairs present but not arranged in a distinct row, usually mixed with straight or evenly curved hairs, (C) V. chamberlini (CASENT0761101) and (D) V. smithi (CASENT0923131)—J-shaped hairs present, arranged in a V-shaped row which does not reach the posterior part of the lateroventral margin of head capsule, usually mixed with straight or evenly curved hairs, and (E) V. pergandei (CASENT0923124)—J-shaped hairs present, many long J-shaped hairs arranged in a distinct row around the outer margin of the ventral region of the head capsule. Photographs by Wade Lee from www.AntWeb.org.

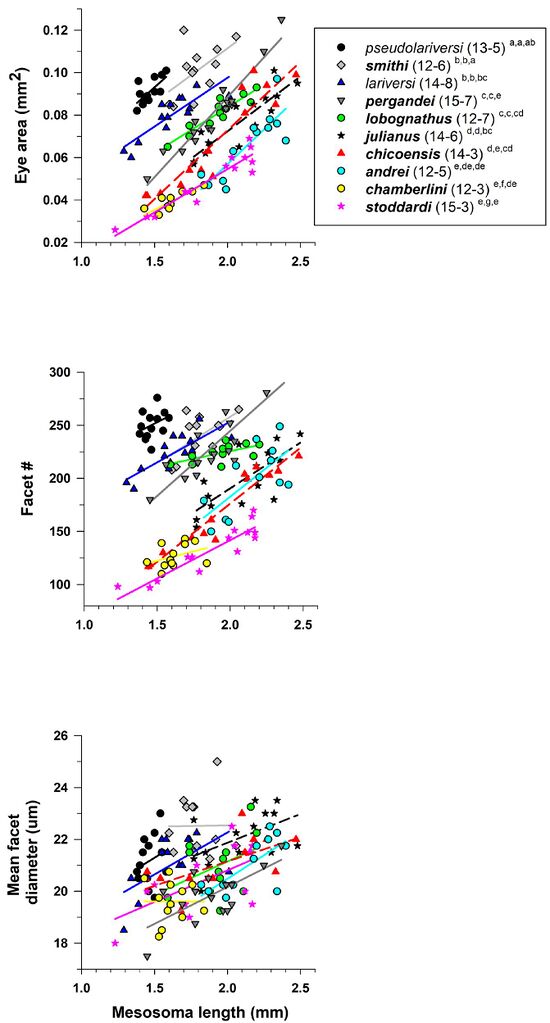

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 6. Photographs of the four categories of increasing psammophore development for species of Veromessor based on number and distribution of long J-shaped hairs on the ventral surface of the head capsule (= hypostomal region) (see text). Photograph of: (A) V. chicoensis (CASENT0923125)—J-shaped hairs mostly absent with scattered straight or evenly curved hairs, (B) V. andrei (CASENT0923140)—J-shaped hairs present but not arranged in a distinct row, usually mixed with straight or evenly curved hairs, (C) V. chamberlini (CASENT0761101) and (D) V. smithi (CASENT0923131)—J-shaped hairs present, arranged in a V-shaped row which does not reach the posterior part of the lateroventral margin of head capsule, usually mixed with straight or evenly curved hairs, and (E) V. pergandei (CASENT0923124)—J-shaped hairs present, many long J-shaped hairs arranged in a distinct row around the outer margin of the ventral region of the head capsule. Photographs by Wade Lee from www.AntWeb.org. Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 53. Eye area (mm2) (A), facet number (B), and mean facet diameter (μm) (C) for pale and dark colored species of Veromessor. Two species are pale (V. lariversi, V. pseudolariversi—open symbols and regular font), while the other eight species are dark (filled symbols and bold font). For each species, number of workers examined and number of colonies they were derived from is given in parentheses. Significant differences (P < 0.05) among species are denoted after each species name by the letters a–g: a > b > c > d > e > f > g; the three sets of letters for each species correspond to panels A, B, and C, respectively. Groupings are based on univariate F tests within MANCOVA followed by pairwise comparisons using a least significant differences test (see also Johnson & Rutowki, 2022).

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 53. Eye area (mm2) (A), facet number (B), and mean facet diameter (μm) (C) for pale and dark colored species of Veromessor. Two species are pale (V. lariversi, V. pseudolariversi—open symbols and regular font), while the other eight species are dark (filled symbols and bold font). For each species, number of workers examined and number of colonies they were derived from is given in parentheses. Significant differences (P < 0.05) among species are denoted after each species name by the letters a–g: a > b > c > d > e > f > g; the three sets of letters for each species correspond to panels A, B, and C, respectively. Groupings are based on univariate F tests within MANCOVA followed by pairwise comparisons using a least significant differences test (see also Johnson & Rutowki, 2022).

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Veromesor andrei occurs in most open habitats from seaside to mountain valleys throughout the California coastal range from southern Oregon to northern Baja California, Mexico, at elevations from 0–2,000 m (Creighton, 1953; Wheeler & Wheeler, 1973). This species occurs in the Baja California desert, California coastal sage and chaparral, California montane chaparral and woodlands, California interior chaparral and woodlands, California Central Valley grasslands, Northern California coastal forests, and Klamath-Siskiyou forests ecoregions, as defined by Olson et al. (2001). There also are several records from higher elevations (> 1,120 m) in the Mohave Desert ecoregion in San Bernardino and Riverside Counties (Figure 10A). We regard the literature record of V. andrei from Ormsby County, Nevada, to be spurious (Wheeler & Creighton, 1934) until it is reverified. (Johnson et al., 2022)

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 10. Geographic distribution of: (A) Veromessor andrei, (B) V. chamberlini, and (C) V. chicoensis. The larger black circle in each panel denotes the type locality. The northernmost locale for V. chamberlini was given only as Santa Clara County, and we have placed this locale near the center of the county.

Johnson et al., 2022, Fig. 10. Geographic distribution of: (A) Veromessor andrei, (B) V. chamberlini, and (C) V. chicoensis. The larger black circle in each panel denotes the type locality. The northernmost locale for V. chamberlini was given only as Santa Clara County, and we have placed this locale near the center of the county.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 43.99833333° to 30.18333333°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

Plowes et al (2014) - Three Nearctic seed harvesting ants in the genus Veromessor (Veromessor pergandei, Veromessor andrei, and Veromessor julianus) employ column foraging to guide workers leaving and returning to the nest. for distributing workers searching for food outside the nest. When foraging first begins for the day, thousands of V. andrei workers emerge from their colony and move along a narrow path away from the nest. These paths, the foraging column, extend from 3 to more than 40 m. At the location where the foraging column comes to an end, workers then disperse in a foraging fan, i.e., individuals leave the trail and forage independently, then return to the column after they have collected a food item (Went et al. 1972; Bernstein 1975; Wheeler and Rissing 1975). Columns may form trunk trails when they lead to a more stable resource (Plowes et al. 2013). The direction taken by a column is determined at the beginning of each foraging bout. Columns always originate at the nest and direction may change between morning and evening and between subsequent days (e.g., Clark and Comanor 1973). In V. andrei, foraging columns often follow the same direction for several successive foraging bouts. The columns function to direct workers to harvesting sites while simultaneously avoiding neighbors (Ryti and Case 1988; Plowes et al. 2014). Inter-colony aggression occurs when columns from neighboring colonies intersect (Wheeler and Rissing 1975; Brown and Gordon 2000).

Plowes et al (2014) combined behavioral analyses in the laboratory and field to investigate chemical communication in the formation of foraging columns in two Nearctic seed harvesting ants, Veromessor pergandei and Veromessor andrei. In the laboratory, V. pergandei were found to use poison gland secretions to lay recruitment trails. GCMS analysis of V. andrei poison glands revealed several volatile substances. Their mass spectra and retention time matched those of (1) 1-phenylethanol (1PE); (2) tridecane; (3) E2-hexadecen-1-ol; (4) pentadecane; (5) hexadecenoic acid; (6) oleic acid; (7) 2-propenoic acid, [3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-, 2-ethylhexyl ester]. A 3 μl of a 0.5–1 ppm solution of 1-phenyl ethanol drawn out along a 40 cm long trail released trail following behavior.

The following notes are provided by Johnson et al., 2022:

Nests of V. andrei occur in open sites in most soil types and consist of one to multiple entrances with irregularly-shaped entrances up to 5 cm in diameter. Nest entrances usually are surrounded by an irregular gravel mound of excavated soil and chaff that ranges up to 60 cm in diameter (Boulton, Jaffee, & Scow, 2003; Creighton, 1953; Snelling & George, 1979; Wheeler & Creighton, 1934). Workers of V. andrei are mostly monomorphic (Wheeler & Creighton, 1934).

Colonies of V. andrei have not been censused, but observations indicate that they contain tens of thousands of workers that form foraging columns up to 20 m long, with workers fanning out to forage at the distal end of the column (Brown & Gordon, 2000; Creighton, 1953; Wheeler & Creighton, 1934); vegetation and debris are removed to construct trails when necessary. Colonies sometimes have more than one foraging column. Colonies forage most days during the foraging season, which typically lasts from late March to late October or early November. Foraging time varies seasonally with changes in temperature: colonies forage during the day when days are cool, they become crepuscular-matinal as temperatures increase, and they forage nocturnally when nights are warm (Brown & Gordon, 2000; Hobbs, 1985). Foraging columns can revisit the same location for multiple days or they can change direction on successive days such that colonies visit the entire area surrounding their nests (Brown & Gordon, 2000; Hobbs, 1985). Neighbors also affect foraging direction because encounters with neighbors on one day increasing the probability of revisiting that area the following day; encounters with neighbors resulted in fighting that typically involve relatively few pairs of ants (Brown & Gordon, 2000). This behavior contrasts with that of Veromessor pergandei, in which foraging columns avoid nearest neighbors (Ryti & Case, 1988a).

Foraging patterns of V. andrei result from chemicals released by several glands. Secretions from the pygidial gland (primarily n-tridecane) appear to initiate the foraging column (Hölldobler et al., 2013), while a trail pheromone (primarily 1-phenylethanol) released from the poison gland maintains recruitment to the foraging fan (Plowes, Colella, Johnson, & Hölldobler, 2014). The recruitment effect from the poison gland is enhanced when adding pygidial gland secretions (Plowes, Colella, et al., 2014). Like other large-colony congeners, workers of V. andrei have a large pygidial gland reservoir with a textured tergal cuticle (Hölldobler et al., 2013).

Mating flights of V. andrei occur in post-dawn hours over an up to several week period from mid-June through July, usually with relatively few sexuals released per day (Brown, 1999b; McCluskey, 1963; Snelling & George, 1979; R.A. Johnson, pers. obs.). Flights are synchronized across colonies, apparently in response to a circadian rhythm in which activity of males increases drastically during early morning hours (McCluskey, 1958, 1963). That photoperiod triggers mating flights is based on observations that males exhibit sharp daily activity peaks under controlled light cycles and that these cycles appear to be under endogenous control. Sexuals fly from the nest and mate in the air (Brown, 1999b; R.A. Johnson, pers. obs.).

Mating frequency for queens of V. andrei is unknown. Dry mass of alate queens averages 7.5 + 0.3 mg. Alate queens contain an average of 44.0 + 1.9 (n = 5) ovarioles, and mated queens contain an average of 1.52 + 0.11 (n = 5) million sperm. Dry mass for virgin males averages 2.1 + 0.1 mg, and they contain an average of 9.15 + 0.64 (n = 3) million sperm (R.A. Johnson, unpub. data).

Little is known about colony founding, but Brown (1999b) observed that founding queens are semi-claustral, i.e., they leave the nest to forage. Brown (1999b) also reported that queens of V. andrei lack storage proteins, inferring that they are obligate foragers, i.e., they cannot rear their first brood of minims without an external food source. Laboratory experiments should examine the founding strategy of V. andrei queens in more detail (e.g., Johnson, 2002, 2006).

Queens of V. andrei also are unusual because dealate queens sometimes occur in foraging columns. Creighton (1953) observed this behavior and suggested that these dealate queens were taken into established nests after mating. These observations were studied by Brown (1999b), who documented that dealate queens occur in foraging columns for about one month, and that all of these dealate queens were uninseminated. The mechanism that causes queens to forego mating and to perform worker-like tasks is unknown, especially in V. andrei, where this behavior cannot be attributed to lack of rains that trigger mating flights. The only other study to examine this behavior in detail found that dealate foraging queens of Pogonomyrmex pima also were uninseminated (Johnson, Holbrook, Strehl, & Gadau, 2007). Dealate queens from mature colonies in several other ant genera also leave the nest to forage (Johnson, 2015; Peeters, 1997).

Most colonies of V. andrei relocate their nest every year, with some colonies relocating nests up to 10 times per year. Relocation was not caused by encounters with their nearest neighbor even though the new nest site was typically more distant from that nearest neighbor. Predation, disease, microclimate, and local resource depletion were suggested as other possible causes of nest relocation (Brown, 1999a). Patterns of relocation were consistent within this population, but differed from patterns at a distant site (Pinter-Wollman & Brown, 2015). Veromessor andrei also affects local abundance and distribution of plants through their seed-harvesting and nest building activites. Workers typically display strong preferences for the seeds of some plant species, which results in changing the density and composition of plant species in areas that foragers visit (Hobbs, 1985; Peters, Chiariello, Mooney, Levin, & Hartley, 2005; but see Brown & Human, 1997). The nest mound itself also consists of a localized microsite that is affected by V. andrei because nest mounds contain higher concentrations of nutrients, a higher abundance and diversity of soil organisms (e.g., fungi, nematodes, microarthropods), and different plant species compared to adjacent non-mound soils (Boulton et al., 2003; Hobbs, 1985; Peters et al., 2005).

Flight Period

| X | X | ||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info; Johnson et al., 2022.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a host for the cricket Myrmecophilus orgeonensis (a myrmecophile) in Canada, United States.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- andrei. Aphaenogaster andrei Mayr, 1886d: 448 (w.) U.S.A. (California).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: U.S.A.: California (no collector’s name).

- Type-depository: NHMW.

- Emery, 1895c: 306 (q.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1972b: 240 (l.); Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988: 95 (k.).

- Combination in Stenamma (Messor): Emery, 1895c: 306;

- combination in Novomessor: Emery, 1915d: 73;

- combination in Novomessor (Veromessor): Forel, 1917: 235; Emery, 1921f: 67;

- combination in Messor: Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 565; Santschi, 1911d: 5; Bolton, 1982: 341 (in text);

- combination in Veromessor: Wheeler, W.M. & Creighton, 1934: 362; Ward, et al. 2015: 73.

- Status as species: Cresson, 1887: 260; Dalla Torre, 1893: 98; Emery, 1895c: 306; Wheeler, W.M. 1904d: 271; Wheeler, W.M. 1910g: 565; Santschi, 1911d: 5; Emery, 1915d: 73; Emery, 1921f: 67; Essig, 1926: 860; Wheeler, W.M. & Creighton, 1934: 362 (redescription); Wheeler, W.M. 1935g: 17; Cole, 1937a: 101; Enzmann, J. 1947b: 152 (in key); Creighton, 1950a: 158; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 799; Creighton, 1953a: 3; Smith, M.R. 1956a: 36 (in key); Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119; Smith, M.R. 1967: 353; Hunt & Snelling, 1975: 21; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1364; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 78; Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1986g: 38; Bolton, 1995b: 252; Ward, 2005: 66.

- Senior synonym of castaneus: Creighton, 1953a: 3; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1364; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 78; Bolton, 1995b: 252.

- Senior synonym of flavus: Creighton, 1953a: 3; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1364; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 78; Bolton, 1995b: 252.

- Distribution: Mexico, U.S.A.

- castaneus. Veromessor andrei subsp. castaneus Wheeler, W.M. & Creighton, 1934: 365 (w.) U.S.A. (California).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated, “a large series”).

- Type-locality: U.S.A.: California, Jacumba (W.M. Wheeler); other syntypes from California, San Diego (W.M. Wheeler).

- Type-depositories: LACM, MCZC.

- Subspecies of andrei: Enzmann, J. 1947b: 152 (in key); Creighton, 1950a: 159; Smith, M.R. 1951a: 799.

- Junior synonym of andrei: Creighton, 1953a: 3; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1364; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 78; Bolton, 1995b: 253.

- flavus. Veromessor andrei subsp. flavus Wheeler, W.M. & Creighton, 1934: 366 (w.) U.S.A. (California).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: U.S.A.: California, Jacumba, 17.viii.1917 (W.M. Wheeler).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Subspecies of andrei: Enzmann, J. 1947b: 152 (in key); Smith, M.R. 1951a: 799.

- Junior synonym of castaneus: Creighton, 1950a: 159.

- Junior synonym of andrei: Creighton, 1953a: 3; Smith, M.R. 1958c: 119; Smith, D.R. 1979: 1364; Snelling, R.R. & George, 1979: 78; Bolton, 1995b: 254.

Type Material

Aphaenogaster andrei

- Lectotype worker (designated by Johnson et al., 2022: 12) from Tres Pinos, San Benito County, California, United States [CASENT0923122] [NHMW].

- Paralectotypes: 8 workers [NHMW], UNITED STATES, California: no location, April 1884; 1 worker [NHMW], California: San Mateo; 12 workers [USNM], California, San Benito County, Tres Pinos.

Veromessor andrei flavus

- Lectotype worker (designated by Johnson et al., 2022: 12) from Jacumba, Sand Diego County, California, United States (W.M. Wheeler leg., 13 August 1917) [USNMENT00529212] [USNM].

- Paralectotypes: 2 workers [USNM], UNITED STATES, California: San Diego County, Jacumba (W.M. Wheeler leg., 13 August 1917).

Veromessor andrei castaneus

- Lectotype worker (designated by Johnson et al., 2022: 12) from Jacumba, Sand Diego County, California, United States (W.M. Wheeler leg., 13 August 1917) [USNMENT00529071] [USNM].

- Paralectotypes: 5 workers [LACM], 3 workers [USNM], UNITED STATES, California: San Diego County, Jacumba (W.M. Wheeler leg., 13 August 1917).

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Wheeler and Creighton (1934) - Length: 4.5-7 mm.

Head, exclusive of the mandibles, four-fifths as broad as long, slightly wider behind the eyes than in front of them, the sides in front of the eyes straight, behind the eyes slightly convex and meeting the occiput in a broadly rounded angle. Occipital border with a broad though very shallow median concavity. Border of the clypeus straight or at most very feebly convex, the median portion feebly sulcate, the lateral portions raised into a narrow ridge or welt which bounds the anterior edge of the antennal fossa. Frontal area opaque. Frontal carinae very narrow and welt-like, slightly divergent above the insertion of the scapes, much more divergent posteriorly where they fuse with the sculpture of the head at a point just behind the posterior border of the antennal fossae. Eyes of moderate size, oval in outline, strongly eon vex, with about sixteen facets in their greatest diameter, their posterior border lying at a point half way between the insertion of the mandible and the occipital border. Antennal scapes slender, the proximal portion dilated to form a trumpet-shaped expansion, distal to this the median portion of the scape somewhat constricted, the apical end only slightly swollen and no larger in diameter than the flared proximal end. When in repose the tip of the scape just reaches the occipital border. Funicular joints, with the exception of the last three, all longer than broad, especially the first joint, which is more than twice as long as broad; joints ten and eleven only slightly longer than broad and notably thicker than the preceding joints, the terminal joint bluntly pointed, longer but no thicker than the preceding two. Mandibles large and stout with the evenly curved outer edge meeting the masticatory margin in a powerful two-cusped terminal tooth. The remaining six or seven teeth much smaller, forming a concave serrated edge to the masticatory margin, the latter meeting the straight inner margin of the mandible at a right angle.

Thorax, seen in profile, with a gibbous promesonotum, the promesonotal suture marked by a somewhat flattened area but not forming a distinct depression; epinotum greatly depressed, the mesoepinotal suture broad and strongly impressed; basal face of the epinotum virtually flat, sloping slightly backward, terminating in two large, straight, divergent spines, which slightly exceed the length of the basal face of the epinotum; declivous face of the epinotum short and concave. Seen from above, the promesonotum is pyriform and notably wider than the rest of the thorax, the sides of the thorax very slightly constricted at the mesoepinotal suture, sides of the epinotum virtually parallel. First joint of the petiole with a rather thick peduncle, which gradually increases in thickness from its anterior end to the base of the node, its ventral surface with a sharp anterior tooth and a low, rounded lamella at its midpoint. Node of the petiole small, its height no greater than the thickness of the peduncle, its anterior face forming a continuous feebly concave slope with the dorsum of the peduncle, the summit acute, the posterior face very declivous and strongly convex, posterior peduncle extremely short. Postpetiole in profile lower than the petiole, the node low and rounded above, with the anterior face longer though less declivous than the posterior face, ventral surface with a prominent V-shaped median impression. Seen from above, the rather narrow petiole is scarcely two-thirds as wide as the campanulate postpetiole. Gaster large. Legs long, the femora slightly swollen.

Head sub opaque, completely covered with rather coarse, wavy rugae which diverge toward the occiput. The interrugal spaces finely granulose and feebly shining. Mandibles shining, with moderately prominent longitudinal striae. Antennal scapes feebly granulose, more shining than the head. Thorax somewhat more opaque than the head, completely covered with irregular rugae, except at the front and lateral edges of the pronotum where they are subparallel. Petiole and postpetiole strongly granulose, with a few short rugae. Gaster smooth and shining, with numerous fine piligerous punctures.

Entire insect covered with glistening whitish hairs which are very unequal in length; the gular hairs forming rather poorly developed ammochaetae, longer than the majority of hairs on the head and thorax but almost equalled in length by a few long hairs which occur on the upper surface of the head, the pronotum, and the coxae of the fore legs. Dorsum of the first gastric segment entirely covered with hairs which are relatively short and more nearly of equal length than those on the head and thorax. Hairs on the remaining abdominal segments confined to the posterior border of each segment. Antennal scapes, femora, and tibiae with numerous, short, erect hairs; those on the tarsi somewhat finer and subappressed; funicular hairs very fine, short, and subappressed, except on the last four joints where they are replaced by golden pubescence.

Color variable. In some specimens the entire insect is reddish black, except for the nodes of the petiole which are reddish. In other specimens only the posterior part of the gaster is black, the first gastric segment castaneous and the remainder of the insect clear, deep red. Not infrequently both the head and gaster are infuscated, leaving only the thorax and nodes of the petiole red.

Karyotype

- See additional details at the Ant Chromosome Database.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Karyotype data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- 2n = 40 (USA) (Taber & Cokendolpher, 1988).

References

- Bolton, B. 1982. Afrotropical species of the myrmecine ant genera Cardiocondyla, Leptothorax, Melissotarsus, Messor and Cataulacus (Formicidae). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Entomology, 46: 307-370 (page 341, Combination in Messor)

- Brown, M.J.F. 1999. Semi-claustral founding and worker behaviour in gynes of Messor andrei. Insectes Sociaux 46(2), 194–195 (doi:10.1007/s000400050133).

- Brown, M.J.F., Bonhoeffer, S. 2003. On the evolution of claustral colony founding in ants. Evolutionary Ecology Research 5: 305–313.

- Creighton, W. S. 1953. New data on the habits of the ants of the genus Veromessor. American Museum Novitates 1612: 1-18. (page 3, Senior synonym of castaneus (and its junior synonym flavus))

- Emery, C. 1895d. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Syst. Geogr. Biol. Tiere 8: 257-360 (page 306, queen described, Combination in Stenamma (Messor))

- Emery, C. 1915k. Definizione del genere Aphaenogaster e partizione di esso in sottogeneri. Parapheidole e Novomessor nn. gg. Rend. Sess. R. Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna Cl. Sci. Fis. (n.s.) 19: 67-75 (page 73, Combination in Veromessor)

- Forel, A. 1917. Cadre synoptique actuel de la faune universelle des fourmis. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 51: 229-253 (page 235, Combination in N. (Veromessor))

- Horna-Lowell, E., Neumann, K.M., O’Fallon, S., Rubio, A., Pinter-Wollman, N. 2021. Personality of ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – underlying mechanisms and ecological consequences. Myrmecological News 31: 47-59 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:047).

- Johnson, R.A., Borowiec, M.L., Snelling, R.R., Cole, A.C. 2022. A taxonomic revision and a review of the biology of the North American seed-harvester ant genus Veromessor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Zootaxa 52061, 1-115 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5206.1.1).

- Mayr, G. 1886d. Die Formiciden der Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 36: 419-464 (page 448, worker described)

- Moura, M.N., Cardoso, D.C., Cristiano, M.P. 2020. The tight genome size of ants: diversity and evolution under ancestral state reconstruction and base composition. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa135 (doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa135).

- Plowes, N. J. R., T. Colella, R. A. Johnson, and B. Holldobler. 2014. Chemical communication during foraging in the harvesting ants Messor pergandei and Messor andrei. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology. 200:129-137. doi:10.1007/s00359-013-0868-9

- Plowes, N.J.R., Johnson, R.A., Holldobler, B. 2013. Foraging behavior in the ant genus Messor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Myrmecological News 18, 33-49.

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. i-xvi, 1199-2209. (page 1364, see also)

- Taber, S. W.; Cokendolpher, J. C. 1988. Karyotypes of a dozen ant species from the southwestern U.S.A. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Caryologia 41: 93-102 (page 95, karyotype described)

- Ward, P.S., Brady, S.G., Fisher, B.L. & Schultz, T.R. 2014. The evolution of myrmicine ants: phylogeny and biogeography of a hyperdiverse ant clade (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Systematic Entomology, DOI: 10.1111/syen.12090

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1972b. Ant larvae of the subfamily Myrmicinae: second supplement on the tribes Myrmicini and Pheidolini. J. Ga. Entomol. Soc. 7: 233-246 (page 240, larva described)

- Wheeler, W. M.; Creighton, W. S. 1934. A study of the ant genera Novomessor and Veromessor. Proc. Am. Acad. Arts Sci. 69: 341-387 (page 362, Combination in Veromessor)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Adams T. A., W. J. Staubus, and W. M. Meyer. 2018. Fire impacts on ant assemblages in California sage scrub. Southwestern Entomologist 43(2): 323-334.

- Backlin, Adam R., Sara L. Compton, Zsolt B. Kahancza and Robert N. Fisher. 2005. Baseline Biodiversity Survey for Santa Catalina Island. Catalina Island Conservancy. 1-45.

- Boulton A. M., Davies K. F. and Ward P. S. 2005. Species richness, abundance, and composition of ground-dwelling ants in northern California grasslands: role of plants, soil, and grazing. Environmental Entomology 34: 96-104

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1937. An annotated list of the ants of Arizona (Hymen.: Formicidae). [part]. Entomological News 48: 97-101.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Des Lauriers J., and D. Ikeda. 2017. The ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California, USA with an annotated list. In: Reynolds R. E. (Ed.) Desert Studies Symposium. California State University Desert Studies Consortium, 342 pp. Pages 264-277.

- Emery C. 1895. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der nordamerikanischen Ameisenfauna. (Schluss). Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Tiere 8: 257-360.

- Fisher B. L. 1997. A comparison of ant assemblages (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) on serpentine and non-serpentine soils in northern California. Insectes Sociaux 44: 23-33

- Holway D.A. 1998. Effect of Argentine ant invasions on ground-dwelling arthropods in northern California riparian woodlands. Oecologia. 116: 252-258

- Hunt J. H. and Snelling R. R. 1975. A checklist of the ants of Arizona. Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science 10: 20-23

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Johnson, R.A. and P.S. Ward. 2002. Biogeography and endemism of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico: a first overview. Journal of Biogeography 29:10091026/

- Mallis A. 1941. A list of the ants of California with notes on their habits and distribution. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 40: 61-100.

- Matsuda T., G. Turschak, C. Brehme, C. Rochester, M. Mitrovich, and R. Fisher. 2011. Effects of Large-Scale Wildfires on Ground Foraging Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Southern California. Environmental Entomology 40(2): 204-216.

- Santschi F. 1911. Formicides récoltés par Mr. le Prof. F. Silvestri aux Etats Unis en 1908. Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 41: 3-7.

- Smith M. R. 1956. A key to the workers of Veromessor Forel of the United States and the description of a new subspecies (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Pan-Pacific Entomologist 32: 36-38.

- Staubus W. J., E. S. Boyd, T. A. Adams, D. M. Spear, M. M. Dipman, W. M. Meyer III. 2015. Ant communities in native sage scrub, non-native grassland, and suburban habitats in Los Angeles County, USA: conservation implications. Journal of Insect Conservervation 19:669–680

- Taber S. W., and J. C. Cokendolpher. 1988. Karyotypes of a dozen ant species from the southwestern U.S.A. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Caryologia 41: 93-102.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Ward P. S. 2005. A synoptic review of the ants of California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 936: 1-68.

- Wheeler G. C. and Wheeler J. 1973. Ants of Deep Canyon. Riverside, Calif.: University of California, xiii + 162 pp

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp.

- Wheeler W. M., and W. S. Creighton. 1934. A study of the ant genera Novomessor and Veromessor. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 69: 341-387.

- Wheeler, William Morton. 1904. Ants from Catalina Island, California in Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 20:269-271.