Anochetus armstrongi

| Anochetus armstrongi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponerinae |

| Tribe: | Ponerini |

| Genus: | Anochetus |

| Species: | A. armstrongi |

| Binomial name | |

| Anochetus armstrongi McAreavey, 1949 | |

This is one of the more widely distributed Australian Anochetus species, occurring from central Queensland south to southern South Australia. It is also the only species occurring in the cooler south-eastern part of the country.

Biologically, these ground nesting ants are found in a range of drier habitats including dry sclerophyll and savannah woodlands, Callitris forests, Casuarina flats, mallee, bluebush steppes and grasslands. They are almost always found as ground foragers or nesting under a wide range of objects on the ground. Workers forage both day and night.

Photo Gallery

Identification

Entire body smooth and shining except for the sculpturing between the frontal carinae and scattered very weak striations on the propodeal dorsum; eyes large (eye length > 0.30mm). The only other Australian species of Anochetus to show similar lack of sculpturing to A. armstrongi is Anochetus avius. Anochetus armstrongi can be separated from this species by its larger eye size (eye length > 0.30mm vs. < 0.25mm), and longer scapes (scape length > 1.05mm vs. < 1.00mm) and legs (mid-tibial length > 0.85mm vs. < 0.80mm, hind femur length > 1.18mm vs. < 1.10mm). It is very similar to Anochetus renatae but differs in having more weakly developed sculpturing on the propodeum, reduced number of erect hairs on the hind tibiae and less bulging eyes. Anochetus armstrongi is also allopatric to both of these species, occurring in south-eastern Australia while A. avius is limited to northern Western Australia and A. renatae is only known from southern Western Australia.

Keys including this Species

- Key to Australian Anochetus Species

- Key to Ponerinae genera of the southwestern Australian Botanical Province

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 22.5045° to -37.51666667°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Australasian Region: Australia (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

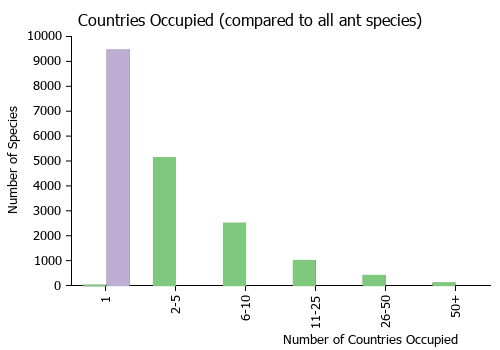

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

|

Castes

Worker

| |

| . | |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- armstrongi. Anochetus armstrongi McAreavey, 1949: 1, figs. 1-6 (w.q.) AUSTRALIA (New South Wales).

- Type-material: holotype worker, 60 paratype workers, 8 paratype queens.

- Type-locality: holotype Australia: New South Wales, Nyngan, 1946 (J.W.T. Armstrong); paratypes with same data.

- Type-depositories: ANIC (holotype); ANIC, BMNH, MCZC (paratypes).

- Status as species: Brown, 1978c: 556, 597; Taylor & Brown, 1985: 20; Taylor, 1987a: 7; Bolton, 1995b: 63; Heterick, 2009: 133; Shattuck & Slipinska, 2012: 7 (redescription).

- Distribution: Australia.

Type Material

- Holotype, worker, Nyngan, New South Wales, Australia, Australian National Insect Collection.

- Paratype, 36 workers, 6 queens, Nyngan, New South Wales, Australia, Australian National Insect Collection.

- Paratype, 4 workers, Nyngan, New South Wales, Australia, Museum of Comparative Zoology.

- Paratype, workers, Nyngan, New South Wales, Australia, The Natural History Museum.

Taxonomic Notes

Brown (1978) and Heterick (2009) included southern Western Australian specimens as part of this species but these are here considered to belong to the separate species Anochetus renatae. Brown did, however, speculate that these western populations may represent a separate species and listed a number of characters that differ from more eastern specimens. He was reluctant to separate them because of the relatively large amount of morphological variation present and the few specimens available for study. Fortunately the situation has improved since then and the presently available material clarifies the taxonomic significance of the characters Brown discussed. It is now possible to develop well defined diagnoses to separate the eastern and western populations and the present evidence suggests that two separate but similar species are involved. As such the western populations are removed from A. armstrongi to the newly described species A. renatae.

Brown (1978) also discussed specimens from northern Western Australia which he treated as belonging to A. armstrongi but Bob Taylor (pers. comm.) described as being "rather like paripungens". In fact these specimens are not part of A. armstrongi but are here considered as belonging to two separate species, Anochetus avius and Anochetus veronicae.

Description

Worker description. Sculpturing on front of head extending slightly beyond eyes. Scapes not reaching posterolateral corners ('lobes') of head; with limited pubescence and few erect hairs. Pronotum smooth and shining. Mesonotum and metapleuron without sculpture, smooth and shining. Propodeum flattened dorsally, with weak transverse striations and only a few scattered very short hairs. Propodeal angle distinct, triangular. Petiolar node in anterior view truncate or weakly concave. Hind tibiae with erect hairs limited to outer surfaces. Colour yellow-brown or light brown with legs yellow or yellow-brown.

Measurements. Worker (n = 12): CI 94–98; EI 24–27; EL 0.33–0.39; HL 1.36–1.57; HW 1.33–1.51; HFL 1.33–1.46; ML 1.69–1.89; MandL 0.67–0.75; MTL 0.95–1.14; PronI 57–60; PronW 0.77–0.87; SL 1.16–1.32; SI 85–92.

References

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1978c. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section B. Genus Anochetus and bibliography. Studia Entomologica. 20:549-638. (page 597, see also)

- Esteves, F.A., Fisher, B.L. 2021. Corrieopone nouragues gen. nov., sp. nov., a new Ponerinae from French Guiana (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). ZooKeys 1074, 83–173 (doi:10.3897/zookeys.1074.75551).

- McAreavey, J. 1949. Australian Formicidae. New genera and species. Proc. Linn. Soc. N. S. W. 74: 1-25 (page 1, figs. 1-6 worker, queen described)

- Shattuck, S.O. & Slipinska, E. 2012. Revision of the Australian species of the ant genus Anochetus (Hymenoptera Formicidae). Zootaxa 3426, 1–28.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Brown W.L. Jr. 1978. Contributions toward a reclassification of the Formicidae. Part VI. Ponerinae, tribe Ponerini, subtribe Odontomachiti. Section B. Genus Anochetus and bibliography. Studia Ent. 20(1-4): 549-638.

- CSIRO Collection

- Debuse V. J., J. King, and A. P. N. Hous. 2007. Effect of fragmentation, habitat loss and within-patch habitat characteristics on ant assemblages in semi-arid woodlands of eastern Australia. Lanscape Ecology 22: 731-745.

- Fisher J., L. Beames, B. J. Rangers, N. N. Rangers, J. Majer, and B. Heterick. 2014. Using ants to monitor changes within and surrounding the endangered Monsoon Vine Thickets of the tropical Dampier Peninsula, north Western Australia. Forest Ecology and Management 318: 7890.

- Shattuck S. O., and E. Slipinska. 2012. Revision of the Australian species of the ant genus Anochetus (Hymeoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 3426: 1-28.