Pogonomyrmex occidentalis

| Pogonomyrmex occidentalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Pogonomyrmecini |

| Genus: | Pogonomyrmex |

| Species group: | occidentalis |

| Species: | P. occidentalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Cresson, 1865) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Common Name | |

|---|---|

| Western Harvester Ant | |

| Language: | English |

Its conspicuous nests and abundance make this an iconic ant of the southwestern United States. This species constructs conical pebble mounds with internal chambers and galleries, with basal entrances, and with peripheral clearings. The colonies are very populous and the workers pugnacious. Pogonomyrmex occidentalis is an active harvester which feeds upon and stores great quantities of seeds. Their nest cones can be seen in aerial photos and have been recorded as persisting for more than than forty years. As each colony is headed by a single queen and will die off once the queen is lost, queens of this species may therefore live more than forty years.

Identification

The position of the basalmost mandibular tooth separates Pogonomyrmex occidentalis from Pogonomyrmex salinus. This tooth is distinctly offset from the basal mandibular margin with which it makes a prominent rounded angle; in salinus the tooth is not at all offset, but instead makes a straight angle with the basal mandibular margin.

Although rather closely related, Pogonomyrmex maricopa and Pogonomyrmex occidentalis are readily distinguishable by a number of strongly contrasting morphological and behavioral characteristic. P. maricopa nests normally only in sand or loose sandy soils whereas occidentalis occupies soils of a notably tighter texture and generally of a gravelly type. Narrow edaphic amplitudes of these species seem to be the rule.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

United States: Kansas, Arkansas, northern Texas (Panhandle), Oklahoma, southwestern North Dakota, western South Dakota and Nebraska, Wyoming (except northwestern pan), Colorado, extreme southeastern Idaho, central and northern New Mexico. Utah (except extreme northwest), Arizona, Nevada, east central California.

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 50.05111111° to 19.752917°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Nearctic Region: Canada, United States (type locality).

Neotropical Region: Mexico.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

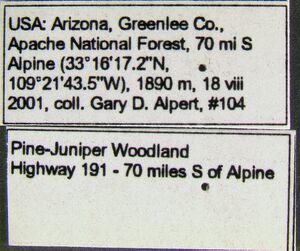

Habitat

Never found in completely arid habitats, most common in higher elevation grasslands, sagebrush sites, oak forests, pinyon juniper forests into pine forests - but always in clearings. (Mackay and Mackay 2002)

Biology

This is a common and, due to their large gravel mounds, conspicuous apecies. Foragers are active during the day, retreating into the nest or into protected sites during the hot part of the day. During the night the ants often block the nest entrance with pebbles. It feeds on seeds and dead insects. It is a very aggressive species and can inflict numerous painful stings in a surprisingly short period of time. Mounds play a role in thermoregulation of the nest. Surfaces exposed to the sun are warmer. The nests are usually covered with pebbles, snail shells or even Indian beads and fossil mammal teeth. The function of the gravel is unknown, but may protect the mound from erosion or may mark the entrance hole (in species with no mound or smaller mounds) to make it easier to find. Monomorium minimum may be found in nests as is the scarabaeid beetle Cremastocheilus saucius. (Mackay and Mackay 2002)

Wheeler and Wheeler (1986):

The mounds of P. occidentalis are built of two types of material: (1) the soil which the ants have excavated in the construction of the subterranean portion of the nest and (2) the fine gravel collected from the surrounding soil surface and placed on the mound. Where gravel is not available a wide variety of substitutes is used. In North Dakota we (Wheeler and Wheeler, 1963) found gypsum, selenite, lignite, petrified wood, empty snail shells, plant debris, and pellets of soil. Paleontologists have collected teeth of small extinct mammals from the surface of mounds. It is even rumored that early prospectors found small gold nuggets, but we were never so lucky. The function of the gravel coating of the mound is probably to prevent erosion by strong winds and torrential rains. Because of the large volume of dead air space (chambers and galleries) the mound also serves as a regulator of temperature.

The mounds (in North Dakota) were generally conoidal. Of the nests for which measurements were recorded the mound varied from 30 cm in diameter and 5 cm in height to 135 cm in diameter and 25 cm in height; average 61 and 14 cm (Wheeler and Wheeler, 1963:114).

Surrounding the mound was a bare area or clearing, which (in North Dakota) reached 3 m in diameter; the average was 1 1/2 m. According to Cole (1932a:140) this was "due to the destruction, by the worker ants, of the vegetation closely surrounding the mounds. The plants are literally 'chewed-down', bit by bit, from the apex to the base." He concluded that the clearing protected the mound from grass fires. We would suggest also that the bare area surrounding the mound makes the sunlight more effective earlier in the day. It must be kept in mind that P. occidentalis occupies a range of cool nights (even in summer) and hot days. Earlier rising enables the workers to get their day's work done before the midday sun in summer heats the ground to lethal temperatures.

In warm weather in North Dakota the workers of P. occidentalis stayed inside the nest during the hottest part of the day, but the entrance remained open. At night the workers retreated into the nest and closed the entrances. Any ant that did not get back in time had to stay outside all night. Workers and the queen overwinter; there is no brood at this time, nor are winged (sexual) forms present. The workers cluster in masses and in a comatose condition, but they revive quickly when warmed; many will survive freezing temperatures overnight. The greatest depth at which ants were found in winter in Wyoming was 277 cm (Lavigne, 1969).

Lavigne reported (1969: 1167) that the actual counts of workers in the 33 nests he excavated varied from 412 to 8,796. There was no direct relation between the size of the mound and the population of the nest. This might be due in part to the fact that small colonies have been known to move into larger abandoned nests.

We had samples of seeds taken from 16 nests in North Dakota. The number of species we found in a nest at the time of collection ranged from 1 to 9. The seeds collected by all the colonies studied were from 30 species of plants (Wheeler and Wheeler, 1963: 116).

The enemies of this ant are lizards and birds. Several species of rodents have been reported robbing the seeds stored in the chambers of the mound.

The myrmecophilous beetle Araeoschizus armatus Horn (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), was found in a colony.

Cole et al. (2001) - We examined the spatial pattern of the ant Myrmecocystus mexicanus and although intraspecific dispersion is highly uniform, colonies were significantly associated with reproductively mature nests of the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Colonies of M. mexicanus were more likely to be found within 3m of P. occidentalis and less likely to be found as far as 10m away. The protein component of the diet of M. mexicanus is almost exclusively dead or moribund workers of P. occidentalis. M. mexicanus appears to associate with one of its consistent food sources.

Flight Period

| X | X | ||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

Source: antkeeping.info.

- Check details at Worldwide Ant Nuptial Flights Data, AntNupTracker and AntKeeping.

- Explore: Show all Flight Month data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Association with Other Organisms

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

Explore: Show all Associate data or Search these data. See also a list of all data tables or learn how data is managed.

- This species is a prey for the tiger beetle Cicindela sp. (a predator) in United States (Willis, 1967; Polidori et al., 2020).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Hyalopterus pruni (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

- This species is a mutualist for the aphid Myzus persicae (a trophobiont) (Jones, 1927; Saddiqui et al., 2019).

Life History Traits

- Queen number: monogynous (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

- Queen mating frequency: multiple (Rissing and Pollock, 1988; Frumhoff & Ward, 1992)

- Mean colony size: 3,880 (Lavigne, 1969; Holldobler & Wilson, 1970; Beckers et al., 1989)

- Foraging behaviour: mass recruiter (Lavigne, 1969; Holldobler & Wilson, 1970; Beckers et al., 1989)

Castes

- Worker

| |

| . | Owned by Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Male (alate). Specimen code casent0104465. Photographer Jen Fogarty, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by CAS, San Francisco, CA, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- occidentalis. Myrmica occidentalis Cresson, 1865: 426 (w.q.) U.S.A. Cole, 1968: 94 (m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1953a: 110 (l.); Taber, Cokendolpher & Francke, 1988: 51 (k.); Taber & Francke, 1986: 274 (gynandromorph). Combination in Pogonomyrmex: Cresson, 1887: 22. Senior synonym of opaciceps, seminigra: Mayr, 1886d: 449; Forel, 1886b: xlii; of ruthveni: Olsen, 1934: 507; of utahensis: Cole, 1968: 95. See also: Smith, D.R. 1979: 1355; Taber & Francke, 1986: 274; Shattuck, 1987: 172.

- seminigra. Myrmica seminigra Cresson, 1865: 427 (m.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of occidentalis: Mayr, 1886d: 449; Forel, 1886b: xlii.

- opaciceps. Pogonomyrmex opaciceps Mayr, 1870b: 971 (diagnosis in key) (w.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of occidentalis: Mayr, 1886d: 449; Forel, 1886b: xlii.

- ruthveni. Pogonomyrmex occidentalis subsp. ruthveni Gaige, 1914: 93 (w.q.m.) U.S.A. Junior synonym of occidentalis: Olsen, 1934: 507.

- utahensis. Pogonomyrmex occidentalis var. utahensis Olsen, 1934: 509 (w.q.m.) U.S.A. Subspecies of occidentalis: Cole, 1942: 365. Junior synonym of comanche: Creighton, 1950a: 128; of occidentalis: Cole, 1968: 95.

Type Material

Type locality: Colorado Territory. A.N.S.P. Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Cole (1968) - HL 1.52-2.09 mm, HW 1.44-2.l3 mm, CI 94.7-101.9, SL 1.10-1.52 mm, SI 71.4-86.8, EL 0.38-0.53 mm, EW 0.19-0.30 mm, OI 25.0-25.4, WL 1.56-2.28 mm, PNL 0.34-0.53 mm, PNW 0.38-0.53 mm, PPL 0.38-0.57 mm, PPW 0.53-0.80 mm.

Mandible as shown in Pl. III, Fig. 1; basalmost tooth larger than penultimate, notably offset from the basal mandibular margin with which it makes a prominent rounded angle; basal mandibular margin straight, comparatively short. Base of antennal scape as in Pl. IV, Fig. 1; broad and pronounced; superior declivity long, not steep; superior lobe broadly truncate; basal flange prominent, evenly and rather strongly curved distad over apex of superior lobe; lip pronounced, broad, strongly curved distad; point weak or absent; longitudinal peripheral carina weakly developed, the depression it borders very shallow.

Contour of thorax, petiole, and postpetiole, in lateral view, as shown in Pl. VI. Fig. 1; surface between apex of anterior mesonotal declivity and base of epinotal spines notably flattened; mesonotum usually distinctly elevated, but sometimes only slightly, above level of pronotum, the promesonotal contour not smooth and even. Epinotal armature generally a pair of long, slender, tapered, pointed spines, but sometimes spines are short or of medium length, more robust, even or u neven in length. Venter of petiolar peduncle without a prominent process. Contour of petiole and postpetiole, viewed dorsally, as in Pl. VII, Fig. 1.

Interrugal spaces of head densely and coarsely punctate and opaque, the punctures producing a beaded appearance; interrugal spaces of thorax densely punctate and opaque, the punctures not obscuring the rugose surface; dorsum of petiolar node generally rather coarsely and irregularly rugose, densely and finely punctate, opaque; rugae of dorsum of postpetiolar node usually sparse, fine, with a transverse trend, confined largely to posterior portion; dorsum of petiolar and postpetiolar nodes sometimes only densely punctate. Base of gastric dorsum with light to moderate shagreening which does not dull the shining surface. Body color light to medium ferrugineous red.

Queen

Cole (1968) - HL 1.98-2.09 mm, HW 2.17-2.32 mm, CI 109.6-111.0, SL 1.41-1.52 mm, SI 65.0-65.5, EL 0.46-0.49 mm, EW 0.27-0.30 mm, OI 23.2-23.4, WL 2.77-2.89 mm, PNL 0.46-0.49 mm, PNW 0.68-0.76 mm, PPL 0.53-0.61 mm, PPW 1.03-1.10 mm.

Largely with the characters of the worker. Contours of thorax, petiole, and post petiole, in lateral view, as shown in Pl. IX, Fig. 1. Epinotum armed with a pair of short, acute spines.

Male

Cole (1968) - HL 1.22-1.44 mm, HW 1.25-1.56 mm, CI 102.5-108.9, SL 0.61-0.76 mm, SI 48.7-48.8, EL 0.53-0.61 mm, EW 0.30-0.34 mm, OI 42.4-43.4, WL 2.28-2.66 mm, PNL 0.38-0.46 mm, PNW 0.49-0.61 mm, PPL 0.49-0.61 mm, PPW 0.7.-0.87 mm.

Head, in full front view, with vertex strongly acute. Mandible as shown in Pl. VIII, Fig. 2; blade broad, wider distally than basally; provided generally with 6 or 7 well-developed teeth; basal most tooth notably larger than penultimate, distinctly offset from the broadly and weakly convex basal mandibular margin with which it makes a pronounced rounded angle, curved somewhat inwardly; masticatory border rather strongly oblique; apical margin straight proximally, weakly convex distally. Antennal scape about one-half again as long as combined lengths of first two flagellar segments; apical segment of flagellum approximately twice the length of penultimate segment, the latter notably longer than broad.

Epinotum armed with a pair of tubercles or weak to strong, broad, blunt or sharp angles. Paramere as shown in Pl. X, Fig. 1, and Pl. XI, Fig. 1; apex of terminal lobe distinctly flattened. Head and thorax deep reddish or blackish brown; petiole, postpetiole, and gaster generally considerably lighter.

Karyotype

- 2n = 32 (USA) (Mehlhop & Gardner, 1982; Taber et al., 1988).

References

- Ahmad, T., Haile, A., Gebremeskel, H., Mekonnen, S. 2012. Reduction of seed harvester ants, Pogonomyrmex spp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), damages by using some insecticides. African Journal of Agricultural Research 7, 5680–5684 (doi:10.5897/ajar12.649).

- Ajayi, O.S., Appel, A.G., Chen, L., Fadamiro, H.Y. 2020. Comparative Cutaneous Water Loss and Desiccation Tolerance of Four Solenopsis spp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Southeastern United States. Insects 11, 418. (doi:10.3390/INSECTS11070418).

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1): 9-36.

- Atanackovic, V. 2013. Understanding contraints and potentials of weed management through seed predation by harvester ants (unpublished Ph.D. thesis).

- Baer, B. 2011. The copulation biology of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 14: 55-68.

- Beckers R., Goss, S., Deneubourg, J.L., Pasteels, J.M. 1989. Colony size, communication and ant foraging Strategy. Psyche 96: 239-256 (doi:10.1155/1989/94279).

- Billen, J. P. J.; Attygalle, A. B.; Morgan, E. D.; Ollett, D. G. 1987. The contents of the Dufour gland of the ant Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Pp. 426-427 in: Eder, J.; Rembold, H. (eds.) 1987. Chemistry and biology of social insects. München: Verlag J. Peperny, xxxv + 757 pp.

- Boulay, R., Galarza, J. et al. 2010. Intraspecific competition affects population size and resource allocation in an ant dispersing by colony fission. Ecology, 91(11), 3312–3321.

- Brown, M.J.F., Bonhoeffer, S. 2003. On the evolution of claustral colony founding in ants. Evolutionary Ecology Research 5: 305–313.

- Bulter, I. 2020. Hybridization in ants. Ph.D. thesis, Rockefeller University.

- Cantone S. 2017. Winged Ants, The Male, Dichotomous key to genera of winged male ants in the World, Behavioral ecology of mating flight (self-published).

- Cole, A. C., Jr. 1968. Pogonomyrmex harvester ants. A study of the genus in North America. Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, x + 222 pp. (page 94, male described, page 95, Senior synonym of utahensis)

- Cole, A.C., Jr. 1934. A brief account of aestivation and overwintering of the Occident Ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis Cresson, in Idaho. The Canadian Entomologist 66: 193-198 (doi:10.4039/Ent66193-9).

- Cole, B.J. 1994. Nest architecture in the western harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Cresson). Insectes Sociaux 41, 401–410 (doi:10.1007/BF01240643).

- Cole, B.J., Haight, K., Wiernasz, D.C. 2001. Distribution of Myrmecocystus mexicanus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Association with Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 94: 59-63 (doi:10.1603/0013-8746(2001)094[0059:DOMMHF2.0.CO;2]).

- Cresson, E. T. 1865b. Catalogue of Hymenoptera in the collection of the Entomological Society of Philadelphia, from Colorado Territory. [concl.]. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Phila. 4: 426-488. (page 426, worker, queen described)

- Cresson, E. T. 1887. Synopsis of the families and genera of the Hymenoptera of America, north of Mexico, together with a catalogue of the described species, and bibliography. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc., Suppl. Vol. 1887: 1-351 (page 22, Combination in Pogonomyrmex)

- Crist T.O. & J.A. MacMahon. 1991. Foraging patterns of Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a shrub-steppe ecosystem: the roles of temperature, trunk trails, and seed resources. Environmental Entomology 20(1), 265-275.

- Delsinne, T., Sonet, G., Arias-Penna, T.M. 2019. Capitulo 21. Subfamilia Paraponerinae. Hormigas de Colombia.

- Ellison, A.M., Gotelli, N.J. 2021. Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and humans: from inspiration and metaphor to 21st-century symbiont. Myrmecological News 31: 225-240 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:225).

- Forel, A. 1886b. Espèces nouvelles de fourmis américaines. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Belg. 30:xxxviii-xlix. (page xlii, Senior synonym of opaciceps and seminigra)

- Horna-Lowell, E., Neumann, K.M., O’Fallon, S., Rubio, A., Pinter-Wollman, N. 2021. Personality of ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – underlying mechanisms and ecological consequences. Myrmecological News 31: 47-59 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:047).

- Jacobs, S. 2020. Population genetic and behavioral aspects of male mating monopolies in Cardiocondyla venustula (Ph.D. thesis).

- Jansen, G., Savolainen, R. 2010. Molecular phylogeny of the ant tribe Myrmicini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160(3), 482–495 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00604.x).

- Lachaud, J.-P., Déjean, A. 1994. Predatory behavior of a seed-eating ant: Brachyponera senaarensis. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 72(2), 145–155 (doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.1994.tb01812.x).

- Lavigne, R.L. 1969 Bionomics and nest structure of Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Ann. Ent. Soc. Amer., 62(50: 1166-1175.

- Lubertazzi D, BJ Cole, and DC Wiernasz. 2013. Competitive advantages of earlier onset of foraging in Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 106:72-78.

- Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston,*Mackay, W. P. and E. Mackay. 2002. The ants of New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY.

- Mayr, G. 1886d. Die Formiciden der Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika. Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 36: 419-464 (page 449, Senior synonym of opaciceps and seminigra)

- Miler, K., Turza, F. 2021. “O Sister, Where Art Thou?”—A review on rescue of imperiled individuals in ants. Biology 10, 1079 (doi:10.3390/biology10111079).

- Moss, A.D., Swallow, J.G., Greene, M.J. 2022. Always under foot: Tetramorium immigrans (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a review. Myrmecological News 32: 75-92 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_032:075).

- Olsen, O. W. 1934. Notes on the North American harvesting ants of the genus Pogonomyrmex Mayr. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 77: 493-514 (page 507, Senior synonym of ruthveni)

- Parker, J.D., Rissing, S.W. 2002. Molecular evidence for the origin of workerless social parasites in the ant genus Pogonomyrmex. Evolution 56: 2017-2028.

- Pirk, G.I., Casenave, J.L.de 2006. Diet and seed removal rates by the harvester ants Pogonomyrmex rastratus and Pogonomyrmex pronotalis in the central Monte desert, Argentina. Insectes Sociaux 53, 119–125 (doi:10.1007/s00040-005-0845-6).

- Plowes, N.J.R., Johnson, R.A., Holldobler, B. 2013. Foraging behavior in the ant genus Messor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Myrmecological News 18, 33-49.

- Polidori, C., Rodriguez-Flores, P.C., Garcia-Paris, M. 2020. Ants as prey for the endemic and endangered Spanish tiger beetle Cephalota dulcinea (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.) (doi:10.1080/00379271.2020.1791252).

- Ruano, F., Tinaut, A., Soler, J.J. 2000. High surface temperatures select for individual foraging in ants. Behavioral Ecology 11, 396-404.

- Shattuck, S. O. 1987. An analysis of geographic variation in the Pogonomyrmex occidentalis complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (Camb.) 94: 159-179 (page 172, see also)

- Siddiqui, J. A., Li, J., Zou, X., Bodlah, I., Huang, X. 2019. Meta-analysis of the global diversity and spatial patterns of aphid-ant mutualistic relationships. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 17: 5471-5524 (doi:10.15666/aeer/1703_54715524).

- Smith, D. R. 1979. Superfamily Formicoidea. Pp. 1323-1467 in: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R., Burks, B. D. (eds.) Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Apocrita (Aculeata). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Pr (page 1355, see also)

- Taber, S. W.; Cokendolpher, J. C.; Francke, O. F. 1988. Karyological study of North American Pogonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Soc. 35: 47-60 (page 51, karyotype described)

- Taber, S. W.; Francke, O. F. 1986. A bilateral gynandromorph of the western harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Southwest. Nat. 31: 274-276 (page 274, gynandromorph described)

- Ulysséa, M.A., Farder-Gomes, C.F., Prado, L.P. 2024. Biological notes, nest architecture, and morphology of the remarkable ant Hylomyrma primavesi Ulysséa, 2021 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Myrmecological News 34, 1-20 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_034:001).

- Wheeler, G. C. and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles.

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1953a [1952]. The ant larvae of the myrmicine tribe Myrmicini. Psyche (Camb.) 59: 105-125 (page 110, larva described)

- Wiernasz, D.C., Hines, J., Parker, D.G., Cole, B.J. 2008. Mating for variety increases foraging activity in the harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Molecular Ecology 17, 1137–1144 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03646.x).

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E. and M Vasquez-Bolanos. 2010. Lista comentada de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) del norte de México. Dugesiana 17(1):9-36

- Albrecht M. 1995. New Species Distributions of Ants in Oklahoma, including a South American Invader. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 75: 21-24.

- Allred D. M. 1982. Ants of Utah. The Great Basin Naturalist 42: 415-511.

- Allred, D.M. 1982. The ants of Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 42:415-511.

- Bare O. S. 1929. A taxonomic study of Nebraska ants, or Formicidae (Hymenoptera). Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA.

- Beck D. E., D. M. Allred, W. J. Despain. 1967. Predaceous-scavenger ants in Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 27: 67-78

- Bestelmeyer B. T., and J. A. Wiens. 2001. Local and regional-scale responses of ant diversity to a semiarid biome transition. Ecography 24: 381-392.

- Browne J. T., R. E. Gregg. 1969. A study of the ecological distribution of ants in Gregory Canyon, Boulder, Colorado. University of Colorado Studies. Series in Biology 30: 1-48

- Buren W. F. 1944. A list of Iowa ants. Iowa State College Journal of Science 18:277-312

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68: 34-39.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1937. An annotated list of the ants of Arizona (Hym.: Formicidae). [concl.]. Entomological News 48: 134-140.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1942. The ants of Utah. American Midland Naturalist 28: 358-388.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1954. Studies of New Mexico ants. VII. The genus Pogonomyrmex with synonymy and a description of a new species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science 29: 115-121.

- Cole A. C., Jr. 1966. Keys to the subgenera, complexes, and species of the genus Pogonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in North America, for identification of the workers. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 59: 528-530.

- Cole, A.C. 1936. An annotated list of the ants of Idaho (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Canadian Entomologist 68(2):34-39

- Cover S. P., and R. A. Johnson. 20011. Checklist of Arizona Ants. Downloaded on January 7th at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/AZants-2011%20updatev2.pdf

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- DuBois M. B. 1985. Distribution of ants in Kansas: subfamilies Ponerinae, Ecitoninae, and Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 11: 153-1229

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Gaige F. M. 1914. Description of a new subspecies of Pogonomyrmex occidentalis Cresson from Nevada. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 27: 93-96.

- Glasier, J. Alberta Ants. AntWeb.

- Gregg, R.T. 1963. The Ants of Colorado.

- Johnson R. A., and C. S. Moreau. 2016. A new ant genus from southern Argentina and southern Chile, Patagonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zootaxa 4139: 1-31.

- Johnson R. Personnal Database. Accessed on February 5th 2014 at http://www.asu.edu/clas/sirgtools/resources.htm

- Johnson R.A., R.P. Overson and C.S. Moreau. 2013. A New Species of Seed-harvester Ant, Pogonomyrmex hoelldobleri (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), from the Mohave and Sonoran Deserts of North America. Zootaxa 3646 (3): 201-227

- Johnson, R.A. 2000. Reproductive biology of the seed-harvester ants Messor julianus (Pergande) and Messor pergandei (Mayr) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Baja California, Mexico. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 9(2):377-384.

- Johnson, R.A. 2002. Semi-Claustral Colony Founding in the Seed-Harvester Ant Pogonomyrmex californicus: A Comparative Analysis of Colony Founding Strategies. Oecologia 132(1):60-67

- Kay, A. 2002. Applying Optimal Foraging Theory to Assess Nutrient Availability Ratios for Ants. Ecology 83(7):1935-1944

- Knowlton G. F. 1970. Ants of Curlew Valley. Proceedings of the Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 47(1): 208-212.

- Lavigne R., and T. J. Tepedino. 1976. Checklist of the insects in Wyoming. I. Hymenoptera. Agric. Exp. Sta., Univ. Wyoming Res. J. 106: 24-26.

- MacKay W. P. 1993. Succession of ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on low-level nuclear waste sites in northern New Mexico. Sociobiology 23: 1-11.

- Mackay, W.P., E.E. Mackay, J.F. Perez Dominguez, L.I. Valdez Sanchez and P.V. Orozco. 1985. Las hormigas del estado de Chihuahua Mexico: El genero Pogonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) . Sociobiology 11(1):39-54

- Mackay, W., D. Lowrie, A. Fisher, E. Mackay, F. Barnes and D. Lowrie. 1988. The ants of Los Alamos County, New Mexico (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). pages 79-131 in J.C. Trager, editor, Advances in Myrmecololgy.

- Mallis A. 1941. A list of the ants of California with notes on their habits and distribution. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 40: 61-100.

- Michigan State University, The Albert J. Cook Arthropod Research Collection. Accessed on January 7th 2014 at http://www.arc.ent.msu.edu:8080/collection/index.jsp

- MontBlanc E. M., J. C. Chambers, and P. F. Brussard. 2007. Variation in ant populations with elevation, tree cover, and fire in a Pinyon-Juniper-dominated watershed. Western North American Naturalist 67(4): 469491.

- O'Keefe S. T., J. L. Cook, T. Dudek, D. F. Wunneburger, M. D. Guzman, R. N. Coulson, and S. B. Vinson. 2000. The Distribution of Texas Ants. The Southwestern Entomologist 22: 1-92.

- Olsen O. W. 1934. Notes on the North American harvesting ants of the genus Pogonomyrmex Mayr. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 77: 493-514.

- Ostoja S. M., E. W. Schupp, and K. Sivy. 2009. Ant assemblages in intact big sagebrush and converted cheatgrass-dominates habitats in Tooele County, Utah. Western North American Naturalist 69(2): 223234.

- Parker, J.D. and S.W. Rissing. 2002. Molecular Evidence for the Origin of Workerless Social Parasites in the Ant Genus Pogonomyrmex. Evolution 56(10):2017-2028

- Paulsen, M.J. 2002. Observations on possible myrmecophily in Stephanucha pilipennis Kraatz (Coleoptera: Scarabaedidae: Cetoniinae) in Western Nebraska. Coleopterists Bulletin 56(3):451-452

- Rees D. M., and A. W. Grundmann. 1940. A preliminary list of the ants of Utah. Bulletin of the University of Utah, 31(5): 1-12.

- Shattuck S. O. 1987. An analysis of geographic variation in the Pogonomyrmex occidentalis complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (Cambridge) 94: 159-179.

- Smith F. 1941. A list of the ants of Washington State. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 17(1): 23-28.

- Smith M. R. 1935. A list of the ants of Oklahoma (Hymen.: Formicidae). Entomological News 46: 235-241.

- Smith M. R. 1953. Pogonomyrmex salinus Olsen, a synonym of Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Cress.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 48: 131-132.

- Strehl, C.-P. and J. Gadau. 2004. Cladistic Analysis of Paleo-Island Populations of the Florida Harvester Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Based upon Divergence of Mitochondrial DNA Sequences. The Florida Entomologist 87(4):576-581

- Taber S. W., J. C. Cokendolpher, and O. F. Francke. 1988. Karyological study of North American Pogonomyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Soc. 35: 47-60.

- Taber S. W., and O. F. Francke. 1986. A bilateral gynandromorph of the western harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Southwest. Nat. 31: 274-276.

- Usnick, S.J. and R.H. Hart. 2002. Western harvester ants' foraging success and nest densities in relation to grazing intensity. Great Plains Research 12:261-273

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Wheeler G. C., and E. W. Wheeler. 1944. Ants of North Dakota. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 11:231-271.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler J. 1989. A checklist of the ants of Oklahoma. Prairie Naturalist 21: 203-210.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1965. Veromessor lobognathus: third note (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 38(1): 55-61.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1986. The ants of Nevada. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, vii + 138 pp.

- Wheeler G. C., and J. Wheeler. 1987. A Checklist of the Ants of South Dakota. Prairie Nat. 19(3): 199-208.

- Wheeler W. M. 1902. New agricultural ants from Texas. Psyche (Cambridge). 9: 387-393.

- Wheeler W. M. 1906. The ants of the Grand Cañon. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 22: 329-345.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1985. A checklist of Texas ants. Prairie Naturalist 17:49-64.

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Montana. Psyche 95:101-114

- Wheeler, G.C. and J. Wheeler. 1988. A checklist of the ants of Wyoming. Insecta Mundi 2(3&4):230-239

- Wight, J.R. and J.T. Nichols. 1966. Effects of Harvester Ants on Production of a Saltbush Community. Journal of Range Management 19(2): 68-71

- Young J., and D. E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publication. Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station 71: 1-42.

- Young, J. and D.E. Howell. 1964. Ants of Oklahoma. Miscellaneous Publications of Oklahoma State University MP-71

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Common Name

- North temperate

- North subtropical

- Tropical

- FlightMonth

- Tiger beetle Associate

- Host of Cicindela sp.

- Aphid Associate

- Host of Hyalopterus pruni

- Host of Myzus persicae

- Karyotype

- Species

- Extant species

- Formicidae

- Myrmicinae

- Pogonomyrmecini

- Pogonomyrmex

- Pogonomyrmex occidentalis

- Myrmicinae species

- Pogonomyrmecini species

- Pogonomyrmex species

- Ssr