Procryptocerus scabriusculus

| Procryptocerus scabriusculus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Procryptocerus |

| Species: | P. scabriusculus |

| Binomial name | |

| Procryptocerus scabriusculus Forel, 1899 | |

The most frequently encountered species of Procryptocerus in Central America.

Identification

Longino and Snelling (2002) - Multiple collections from each region reveal little within-region variation, and the shared characters (face sculpture for Venezuela and Colombia, vertex sculpture for Colombia and Central America) are quite consistent. Whether these are three allopatric lineages or points along a continuum of geographic variation is unknown. A possible phylogeny is (Central America [Colombia, Venezuela]), with the face sculpture common to Colombia and Venezuela being apomorphic, and the vertex sculpture in Venezuela being autapomorphic.

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 24.52827° to -2.916666667°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Belize, Colombia, Costa Rica (type locality), El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Venezuela.

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

Longino and Snelling (2002) - Procryptocerus scabriusculus is the most frequently encountered species of Procryptocerus in Central America. Unlike most species, P. scabriusculus is most often found in dry habitats, roadsides, and second growth vegetation. Nest sites appear to be ephemeral, mostly in dead stems (records include stems of Acacia, Spilanthes and Baccharis trinerva), although nests have been found in live stems. A Creighton collection from Mexico was ‘‘in Cecropia,’’ presumably an opportunistic occurrence in a sapling. Many of the specimens at USNM were on orchid plants intercepted by inspectors at U.S. entry ports. The orchids were most often Oncidium and Cattleya, but this probably reflects the preferences of orchid enthusiasts rather than the preferences of P. scabriusculus. Skwarra (1934) describes five colonies, three of which were in dead wood, one in hollow twigs, and one in a reed (from Kempf, 1951).

Wheeler (1984) observed the behavioral repertoire of a captive colony of P. scabriusculus and used the results to discuss the phylogenetic significance of behavioral traits within the Cephalotini. The study took place in central Costa Rica, and in the course of the study, four colonies were examined. At least one of the colonies was polydomous, in a cluster of twigs from a Spondias tree, and three colonies were polygynous, with up to 27% of the adult population composed of queens. Longino has observed both monogynous nests and one polygynous nest (with three dealate queens) near Monteverde, Costa Rica.

Workers forage at dusk, nocturnally, or both; queens and males occur at lights at night, and sexuals have been observed leaving the nest at night (Snelling, 1968). Ward collected alate queens and males at lights at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico.

Gillette et al. (2015) in a Chaipas, Mexico field study of twig-nesting ants in coffee plants found P. scabriusculus occurred in 11% of the twigs with nests. All of its nests were between 750-1450 m. The relative abundance of Pseudomyrmex ejectus increased and P. scabriusculus decreased with an increasing number of available hollow twigs. Based on observations of competition for artificial nest sites in the lab, P. scabriusculus is a poor competitor, losing ~60 percent of competitive encounters for access to nests (S. Philpott, unpubl. data). In sites with more hollow twigs, both number of twig-nesting ants and species richness increases, and P. scabriusculus may be eliminated from twigs by more aggressive ants in these sites.

Philpot et al. (2018) reported this species was one of the most common ants in an experimental study examining colonization of twigs in shade coffee forests in Chiapas, Mexico (17.2% of the 202 nests found in 796 recovered twigs).

Castes

Worker

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Worker. Specimen code casent0246128. Photographer Andrea Walker, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

| |

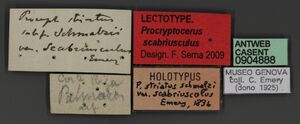

| Type of unavailable quadrinomial: Procryptocerus striatus schmalzi scabriusculus. Worker. Specimen code casent0904888. Photographer Z. Lieberman, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by MSNG, Genoa, Italy. |

Queen

Images from AntWeb

| |

| Queen (alate/dealate). Specimen code casent0246127. Photographer Andrea Walker, uploaded by California Academy of Sciences. | Owned by USNM, Washington, DC, USA. |

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- scabriusculus. Procryptocerus striatus r. scabriusculus Forel, 1899c: 45 (w.) COSTA RICA. [First available use of Procryptocerus striatus subsp. schmalzi var. scabriusculus Emery, 1894c: 198; unavailable name.] Kempf, 1951: 91 (q.); Snelling, R.R. 1968a: 2 (m.); Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1973b: 82 (l.). Raised to species: Kempf, 1951: 89. See also: Longino & Snelling, 2002: 26.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Longino and Snelling (2002) - (n = 1, Costa Rica): HW 1.286, HL 1.163, SL 0.768, EL 0.306, MeL 1.503, MeW 0.955, PrW 0.679, PrL 0.307, PrS 0.298, PrT 0.606, MTL 0.827, MFL 0.911, MFW 0.339, PtL 0.434, PtW 0.431, PpW 0.549, PtH 0.395, AL 1.459, AW 1.173, ASW 0.018.

Head subcircular; vertex flat, sharply differentiated from face by vertex margin, which is entire and somewhat crenate; face evenly convex; in lateral view, anterior portion of clypeus curves ventrad, more strongly curved than general curvature of face and posterior clypeus; frontal carina thickened and laterally flattened just posterior to torulus, ending on dorsum of torulus; vertex shiny, with thin, widely spaced, somewhat irregular, and at times nearly absent longitudinal rugae (Central America, Colombia) or with dense, regular, pronounced longitudinal striae (Venezuela); face sculpture dominated by irregular shallow striae, with foveae not clearly formed and, if present, relatively large (Central America), or striae on the face thickened and nearly fused, isolating smaller, well-formed, teardrop-shaped foveae, and the areolate microsculpture more pronounced, giving the face a granular, less shiny appearance (Colombia, Venezuela); clypeus irregularly longitudinally striate with a few arcing transverse striae at anterior border; genae foveate; mandibles coarsely longitudinally striate; undersurface of head longitudinally striate; scapes with a flanged skirt at base, partially covering neck and condyle; scape weakly flattened, curving and gradually widening distally; scape finely and superficially microareolate dorsally, coarsely rugose on anterior edge; eyes in anterior view convex, asymmetrically skewed ventrally.

Promesonotum in dorsal view with rounded anterior margin, straight to weakly convex sides which converge to base of propodeum; humeri forming obtuse to subacute angles; lateral lobes of mesonotum not or only weakly elevated or projecting, usually approximating right angles aligned with the body axis; anterior border of pronotum with row of coarse foveae, rest of promesonotum and dorsal face of propodeum longitudinally striate; dorsal face of propodeum with produced lateral lobes which extend about half to two-thirds the length of the dorsal face; lateral lobes rounded posteriorly; propodeal spines generally subequal in length to dorsal face, but varying from shorter to longer; dorsal face of propodeum curving into approximately perpendicular posterior face, dorsal striae extend about halfway down posterior face, rest smooth and shining; in lateral view, promesonotum evenly convex; propodeal suture shallow; sides of pronotum flat, meeting dorsal face at distinct angle; lateral face pronotum, anepisternum, katepisternum, and lower portion of lateral face of propodeum with coarse longitudinal striae; femora strongly swollen, spindle-shaped; exterior surfaces of tibiae coarsely rugose; posterior face of forefemur smooth and shining or weakly striate.

Petiole short and squat, anterior face coarsely transversely rugose (smooth in some Mexican specimens); posterior face and dorsum of postpetiole irregularly longitudinally striate; first gastral tergite longitudinally striate throughout; interspaces microareolate, giving a subopaque or granular appearance to gaster; longitudinal striae usually do not or only weakly extend onto second gastral tergite; first gastral sternite subopaque to somewhat shiny with uniformly distributed small puncta, grading to patches of longitudinal rugulae or striae anterolaterally.

Face, dorsum of mesosoma, petiole, postpetiole, and gaster with sparse, short, erect to suberect setae; setae relatively longer and more abundant on petiole, postpetiole, and anterior portion of gaster; setae stiff but not strongly flattened.

The worker is also thoroughly described by Kempf (1951).

Queen

Longino and Snelling (2002) - (n = 1, Costa Rica, LACM ENT 140413): HW 1.205, HL 1.146, SL 0.742, EL 0.392, MeL 1.943, MeW 1.104, MTL 0.867, MFL 0.973, MFW 0.308, PtL 0.512, PtW 0.443, PpW 0.585, PtH 0.431, AL 1.709, AW 1.335.

Similar to worker in most respects; face relatively more foveate and less distinctly striate; foveae relatively large and nearly confluent in Mexican specimens, smaller and interspaces more strialike in Costa Rican specimens, foveae very small and interspaces smooth with microareolate sculpture in Colombian specimens; pronotum coarsely foveate; mesoscutum, axillae, and scutellum with elongate foveae; dorsal face of propodeum longitudinally to obliquely striate.

See Kempf (1951) for a full description.

Male

See Snelling (1968).

Type Material

Longino and Snelling (2002) - Holotype worker: Costa Rica, Palmares [108039N, 848269W] (Alfaro) Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Genoa (examined).

References

- Forel, A. 1899d. Formicidae. [part]. Biol. Cent.-Am. Hym. 3: 25-56 (page 45, worker described)

- Franco, W., Ladino, N., Delabie, J.H.C., Dejean, A., Orivel, J., Fichaux, M., Groc, S., Leponce, M., Feitosa, R.M. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674, 509–543 (doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4674.5.2).

- Gillette, P. N., K. K. Ennis, G. D. Martinez, and S. M. Philpott. 2015. Changes in Species Richness, Abundance, and Composition of Arboreal Twig-nesting Ants Along an Elevational Gradient in Coffee Landscapes. Biotropica. 47:712-722. doi:10.1111/btp.12263

- Jansen, G., Savolainen, R. 2010. Molecular phylogeny of the ant tribe Myrmicini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160(3), 482–495 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00604.x).

- Kempf, W. W. 1951. A taxonomic study on the ant tribe Cephalotini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Rev. Entomol. (Rio J.) 22: 1-244 (page 91, queen described; page 89, Raised to species)

- Longino, J.T. and Snelling, R.R. 2002. A taxonomic revision of the Procryptocerus of Central America. Contributions in Science. 495:1-30. (page 26, see also)

- Meurville, M.-P., LeBoeuf, A.C. 2021. Trophallaxis: the functions and evolution of social fluid exchange in ant colonies (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 31: 1-30 (doi:10.25849/MYRMECOL.NEWS_031:001).

- Philpott, S. M., Z. Serber, and A. De la Mora. 2018. Influences of Species Interactions With Aggressive Ants and Habitat Filtering on Nest Colonization and Community Composition of Arboreal Twig-Nesting Ants. Environmental Entomology. 47:309-317. doi:10.1093/ee/nvy015

- Snelling, R. R. 1968a. Taxonomic notes on some Mexican cephalotine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Contr. Sci. (Los Angel.) 132: 1-10 (page 2, male described)

- Wheeler, D. E. 1985 ("1984"). Behavior of the ant, Procryptocerus scabriusculus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with comparisons to other cephalotines. Psyche (Cambridge) 91:171-192. [1985-04-22]

- Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1973b. Ant larvae of four tribes: second supplement (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Psyche (Camb.) 80: 70-82 (page 82, larva described)

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Emery C. 1894. Studi sulle formiche della fauna neotropica. VI-XVI. Bullettino della Società Entomologica Italiana 26: 137-241.

- Fernández, F. and S. Sendoya. 2004. Lista de las hormigas neotropicales. Biota Colombiana Volume 5, Number 1.

- Forel A. 1912. Formicides néotropiques. Part II. 3me sous-famille Myrmicinae Lep. (Attini, Dacetii, Cryptocerini). Mémoires de la Société Entomologique de Belgique. 19: 179-209.

- Franco W., N. Ladino, J. H. C. Delabie, A. Dejean, J. Orivel, M. Fichaux, S. Groc, M. Leponce, and R. M. Feitosa. 2019. First checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of French Guiana. Zootaxa 4674(5): 509-543.

- INBio Collection (via Gbif)

- Kempf W. W. 1951. A taxonomic study on the ant tribe Cephalotini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Revista de Entomologia (Rio de Janeiro) 22:1-244

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Larsen, A., and S. M. Philpott. 2010. Twig-nesting ants: the hidden predators of the coffee berry borer in Chiapas, Mexico. Biotropica 42: 342-347.

- Longino J. T. and Snelling R. R. 2002. A taxonomic revision of the Procryptocerus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Central America. Contributions in Science (Los Angeles) 495: 1-30

- Longino J. et al. ADMAC project. Accessed on March 24th 2017 at https://sites.google.com/site/admacsite/

- Maes, J.-M. and W.P. MacKay. 1993. Catalogo de las hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia 23.

- Philpott S. M., I. Perfecto, and J. Vandermeer. 2006. Effects of management intensity and season on arboreal ant diversity and abundance in coffee agroecosystems. 15: 139-155.

- Philpott, S.M. and P.F. Foster. 2005. Nest-site limitation in coffee agroecosytems: Artificial nests maintain diversity of arboreal ants. Ecological Applications 15(4):1478-1485

- Philpott, S.M., P. Bichier, R. Rice, and R. Greenberg. 2007. Field testing ecological and economic benefits of coffee certification programs. Conservation Biology 21: 975-985.

- Quiroz-Robledo L., and J. Valenzuela-Gonzalez. 1995. A comparison of ground ant communities in a tropical rainforest and adjacent grassland in Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist 20(2): 203-213.

- Vasquez-Bolanos M. 2011. Checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Mexico. Dugesiana 18(1): 95-133.

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133